Op-Ed: Utilising Local Capacities in the Arctic

How can small-scale local capacities be developed and utilised across Arctic regions when responding to maritime emergency incidents?

This is an opinion piece written by external contributors. All views expressed are the writer's own.

The number of small-scale maritime emergency incidents occurring in Arctic waters is increasing.[i] Demands are made for national governments to invest in and sustain relatively expensive Arctic capacities, such as coast guard vessels, long-range helicopters, and oil-spill response units. An often-overlooked dimension, however, are the local resources already present in Arctic communities. Albeit few and far between, Arctic communities is the foundation emergency management in the north must be built on. The question is: how can we utilise these capacities better, across the Arctic region?

This brief article is based on a report published by the Centre for Military Studies (CMS) in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Click here to read the full report.

Understanding local efforts

There is growing demand for the re-consideration of investments and utilisation on every level. Not surprisingly, each part of the Arctic has a unique emergency response set-up, with a combination of civilian and military capacities located inside or outside of the region. Much of this capacity is managed on a national level, through units such as the coast guard, the navy, airborne search and rescue services, and environmental protection agencies. These units are in turn under the structure of the Ministry of Justice, Defence, or Fisheries and Oceans, or the military itself.

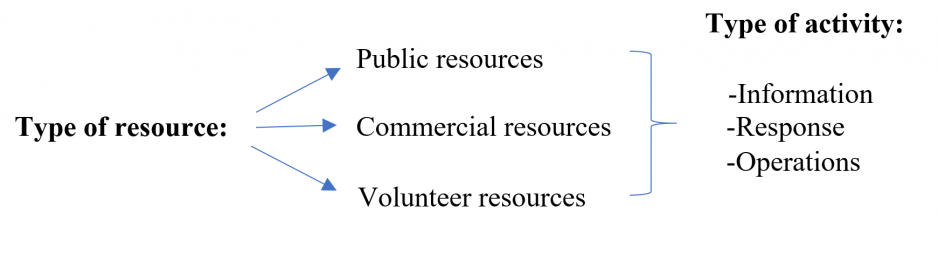

In each Arctic region, there are also a number of communities that have additional capabilities to assist as a maritime emergency unfolds. Emergencies can take the form of a sinking cruise ship, leaking oil, or small vessels missing, to mention some. Capacities to deal with these various forms are naturally not uniform. Yet, the local level has an important role to play in each scenario, with various combinations of public, commercial, and volunteer assets working in tandem. Borrowing from a 2012-report by Kristensen, Hoffmann, and Petersen concerning volunteer engagement on Greenland, locally based activities (public, commercial, and volunteer) can be roughly divided into three types; information, response, and operations.[ii]

I have chosen to separate the various types of local resources and capacities into these 3 x 3 groups, although they are by no means exclusive. They often blend into each other and, crucially, all the available resources are drawn into the response effort in a large-scale emergency. Yet the categories help distinguish between different types of available assets, thereby helping to conceptualise where improvements might be made.

- Information activities, such as training, education, and regulations concerning equipment and operations, can cover large gaps to help reduce the number of dire situations in the Arctic. Similarly, the oil spill training by local organisations, such as the WWF’s efforts in North Norway, provide an example of how to enhance local capacity in a cost-effective manner.

- Response activities, such as recruiting locals and their vessels under an umbrella organisation (e.g. the Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary or the Icelandic Association for Search and Rescue (ICE-SAR)), constitute another relatively cost-efficient remedy to local capacity concerns. Similarly, recruiting local fishermen and outfitting fishing vessels to handle oil spill response equipment can help provide additional layers of response.

- Operation activities, such as regular surveillance and monitoring conducted by the Canadian Rangers or by regular government agencies tasked with maritime safety in the north, are critical in the Arctic, albeit more exhaustive to fund and manage.

Room for improvement

From the range of efforts examined, the debate concerning Arctic preparedness and response requires further nuance. Distinction must be drawn between large-scale maritime incidents and closer-to-shore emergency situations. Community volunteers and mandatory training can go a long way to supporting the latter but have a limited impact on the former.[iii] When (or if) an oil spill reaches shore, local efforts can be organised to assist the clean-up. The first response to a sinking oil tanker or a cruise ship will inevitably be a combination of private and public assets. Another crucial point beyond saving the passengers off a sinking cruise ship is the impact of tourists stranded in a small Arctic community with limited resources.

This report has outlined a number of recommendations for further enhancing Arctic emergency response capacities:

Information:

- Improve the spread of information concerning offshore safety and survival for the local population.

- Mandate training/exercise participation for maritime actors.

- Mandate so-called ‘self-rescue’ training and equipment for maritime tourists.

- Organise ‘how to’ campaigns in local communities together with relevant non-profit organisations.

- Make use of the Arctic engagement of non-profit organisations with additional resources, like the WWF and Red Cross, to create projects aimed at local capacity enhancement.

Response:

- Increase the number of vertical and horizontal exercises between the various local actors.

- Enhance community role-clarification with clearly defined lines of responsibility in preparation for large-scale incidents.

- Explore how local maritime industries can be further included in a system or network for local emergency response.

Operations (permanent):

- Every Arctic community has some form of local engagement in case of an emergency. It is thus up to the local and national governments to provide a framework in which these resources can be further improved and utilised.

- Explore the options for a maritime component to the already existing schemes, such as the Canadian Rangers or Longyearbyen Red Cross.

- Consider establishing a dedicated tool or hub for learning and knowledge enhancement concerned with maritime emergency management that can work on both the local and national levels by informing communities and the public debate.

These points are not uniformly tailored to all Arctic regions, yet they pinpoint the room for increased efforts to the benefit of the given Arctic state and its local northern communities before the situation becomes direr.

Not everything can be solved locally…

Regardless of local capacity enhancement, federal or national governments also have a role to play in managing emergency situations in the Arctic. The maritime domain is challenging, and local resources can only go so far. Tellingly, a 2016 report from the Danish Ministry of Defence recognises that, while important, a Greenlandic Volunteer Force will only be able to assist in maritime emergency incidents within three nautical miles.[iv]

In northern Norway in general and on Svalbard in specific, public authorities together with integral actors, such as Store Norske, provide the core of local capabilities, and there is no volunteer force dedicated to the maritime region. The Icelandic ICE-SAR organisation – probably the most encompassing volunteer effort in this study – seems to be the only system aimed directly at maritime emergency response. Even there, however, capacities are limited in the face of a severe, far-from-shore incident.

Most of the local schemes outlined also require some form of funding. Albeit impressive, selling fireworks (as in the case of ICE-SAR) is only possible in relatively populated parts of the Arctic or in areas where fireworks are in continuous, high demand. Longyearbyen, with 2 100 inhabitants, and Nunavut, with vast distances between communities, struggle to reach the critical mass needed to financially support considerable volunteer organisations. In both cases, there is dependence on a broader national framework, such as the Red Cross in Norway or the various air/sea/land organisations in Canada.

The Rangers in Canada and the envisioned Greenlandic Volunteer Force also require permanent funding to cover administration and personnel costs. This funding must come from national institutions, like the armed forces. Obviously, some volunteer efforts are costlier than others. Providing first-aid training and land-based SAR in Arctic communities is relatively inexpensive compared to the acquisition and use of maritime vessels or airborne capacities that require infrastructure, training, and fuel.

These limitations entail a symbiotic relationship between the various layers of public administration. Local communities are unable to procure new maritime vessels or helicopters. When they do go to such lengths under the umbrella of a local organisation, it is even more impressive, as costly infrastructure projects and investments in emergency response equipment are by definition beyond their scope. Here, federal/national governments have an active role to play. Similarly, central governments can provide the financial and institutional structures required to organise volunteer or semi-professional emergency response efforts in the Arctic.

As outlined in this report, the local level can add an additional or supplementary layer to emergency preparedness in the Arctic and help alleviate the pressures faced by national governments; yet it cannot replace public efforts. Another layer is international cooperation. As with local capacity development, expanding and improving such collaboration can help improve scarce national resources.

Different types of Emergencies

Many reports and studies on this topic also argue that the focus should shift away from ‘big crisis’ incidents and debates concerning ice-breakers towards local communities and their emergency response needs.[v] Although I strongly support a more holistic (and less ice-breaker-focused) debate, there should be a clear, practical, and conceptual separation between the various types of demands. Managing a sinking cruise ship with 1500 passengers 40 nautical miles off the coast of Greenland does not require the same tools and capacities as dealing with local inhabitants requiring SAR on land or ice.[vi] Discussing these issues like they are the same under an umbrella of ‘Arctic emergency response’ risks conflating two very different sets of issues.

In fact, not only do these emergency situations require different sets of resources and capacities, they also take place in two different domains, namely in or around communities versus the offshore. A cruise ship might run aground far from northern communities. Yet there are spill-over effects. A large-scale maritime incident might possibly affect nearby local communities. Similarly, capacities can be developed to serve both types of incidents. Still, this categorisation must be recognised and managed, albeit not under the same banner. Arguing for one set of concerns over the other risks downplaying the severity in each set of incidents. If concern in a community revolves around being stranded on moving ice or rescuing local fishermen, capacities to manage offshore oil spills or a large-scale cruise ship evacuation might not be best suited. Moreover, conflating these issues tends to argue for a hierarchy in which the one set of concerns trumps the other.

The discussion concerning the 2016 voyage of the luxury cruise ship Crystal Serenity highlights some of these key dimensions.[vii] In the event of an accident onboard the vessel, a small local community in Nunavut – most likely located at some distance from the ship – can initially provide limited assistance. Efforts to rescue passengers from the ship would first come from the British research vessel RSS Ernest Shackleton, hired to pair up with the Crystal Serenity along its voyage. Thereafter, public efforts from Canada through its Coast Guard and Air Force would be employed. In the second phase of the response effort, local community capacity might be utilised. However, communities might be strained from hosting a high number of elderly cruise ship passengers for an extended period, depleting local resources that can only be replenished with air or sea transport.

Equally important – and more likely to occur frequently – small-scale incidents involving local fishermen and local transport demand attention in the Arctic. Here, community efforts are better suited and can – as in the example of Nunavik’s acquisition of its own rescue vessels[viii] – add to non-existing or limited public capacities. Similarly, including private sector companies already operating in the area in more formalised arenas for dialogue and response is a cost-effective measure to enhance resources to draw on in the case of an emergency. Nonetheless, any utilisation of local capacities and volunteer efforts requires some form of structure in addition to funding and an engaged local population. On all these accounts, intervention from the local, regional, or national government is crucial to provide the basic support that spurs local efforts.

Small efforts, large effects

One key take-away is that a great deal of unexplored space for further research remains, particularly regarding international cooperation and local governance structures. Yet this report has also identified several measures that can help improve local capacities across the north. Similarly, conceptual nuance is needed when discussing maritime emergency management.

The risk of a cruise ship sinking and the disappearance of a small boat require very different responses. Capacity, however, is lacking to deal with both types. The good news is that relatively limited efforts can have disproportionately large effects in a region where resources are few and far between.

[i] See for example Allianz, “Safety and Shipping Review 2015” (Munich, 2015), http://www.agcs.allianz.com/assets/PDFs/Reports/Shipping-Review-2015.pdf; Odd Jarl Borch et al., “Maritime Activity in the High North - Current and Estimated Level up to 2025,” 2016, 1–130; Sima Sahar Zerehi, “Nunavut Officials Press for Arctic Search and Rescue Base,” CBC News: North, March 7, 2016, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/arctic-search-and-rescue-needs-1.3477252.

[ii] Kristian Søby Kristensen, Rune Hoffmann, and Jacob Petersen, Samfundshåndhævelse I Grønland: Forandring, Forsvar Og Frivillighed (Copenhagen, Denmark: Centre for Military Studies, University of Copnehagen, 2012), http://cms.polsci.ku.dk/cms/samfhaand/Samfundsh_ndh_velse_i_Gr_nland.pdf/.

[iii] Jessica M. Shadian, “Thinking about Search and Rescue from the Bottom up,” The Arctic Journal, July 19, 2016, 1–6, http://arcticjournal.com/opinion/2476/thinking-about-search-and-rescue-bottom.

[iv] Underarbejdsgruppe Involvering og Ansættelse, “Bilag 11 - Særlig Analyse Vdr. Involvering Og Ansættelse” (Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016), 148.

[v] Bernard Funston, “Emergency Preparedness in Canada’s North: An Examination of Community Capactiy” (Toronto, ON, 2014); Brynn Goegebeur, “Canadian Arctic Search and Rescue: An Assessment,” no. November (2014), http://www.ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/31976.

[vi] Zerehi, “Nunavut Officials Press for Arctic Search and Rescue Base.”

[vii] Karen Schwartz, “As Global Warming Thaws Northwest Passage, a Cruise Sees Opportunity,” New York Times, July 6, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/10/travel/arctic-cruise-northwest-passage-greenpeace.html; Michael Byers, “Arctic Cruises: Fun for Tourists, Bad for the Environment,” The Globe and Mail, April 18, 2016, http://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/arctic-cruises-great-for-tourists-bad-for-the-environment/article29648307/.

[viii] Greg Younger-Lewis, “Nunavik Rescue Efforts to Get $1.5-Million Boost,” Nunatsiaq Online, December 12, 2003, http://www.nunatsiaqonline.ca/archives/31212/news/nunavik/31212_01.html; Kieran Oudshoorn, “12 New Nunavut, Nunavik Coast Guard Auxiliaries in the Works,” CBC News, February 26, 2016, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/nunavik-nunavut-coast-guard-auxiliary-1.3466211.