US fisheries diplomat “hopeful” of Arctic moratorium

Ambassador Balton: a deal can be struck “with a bit of creativity and some good will” (Photo: Arctic Circle)

The US diplomat leading negotiations to delay the opening of the central part of the Arctic Ocean to commercial fishing until scientists have gathered enough information in order establish regulations to prevent overfishing says the next round of talks will be the final session.

David Balton, the top US State Department official dealing with fisheries issues, told participants in the Arctic Circle conference in Reykjavík on Sunday that the sole outstanding issue preventing the nine countries taking part in the negotiations together with the EU from agreeing on the terms of a moratorium was the so-called trigger mechanism, a set of conditions that needed to be met before fishing could commence.

Optimistic

Mr Balton expressed optimism about the prospects for an agreement during the November 28-30 meeting in Washington, the sixth round of talks, but cautioned that “nothing [about the deal] is agreed, until everything is agreed”, pointing out that an agreement had been close even before the previous round of negotiations, in March, in Reykjavík.

“But I am convinced that with just a little bit of creativity and some good will, we will get there,” he said.

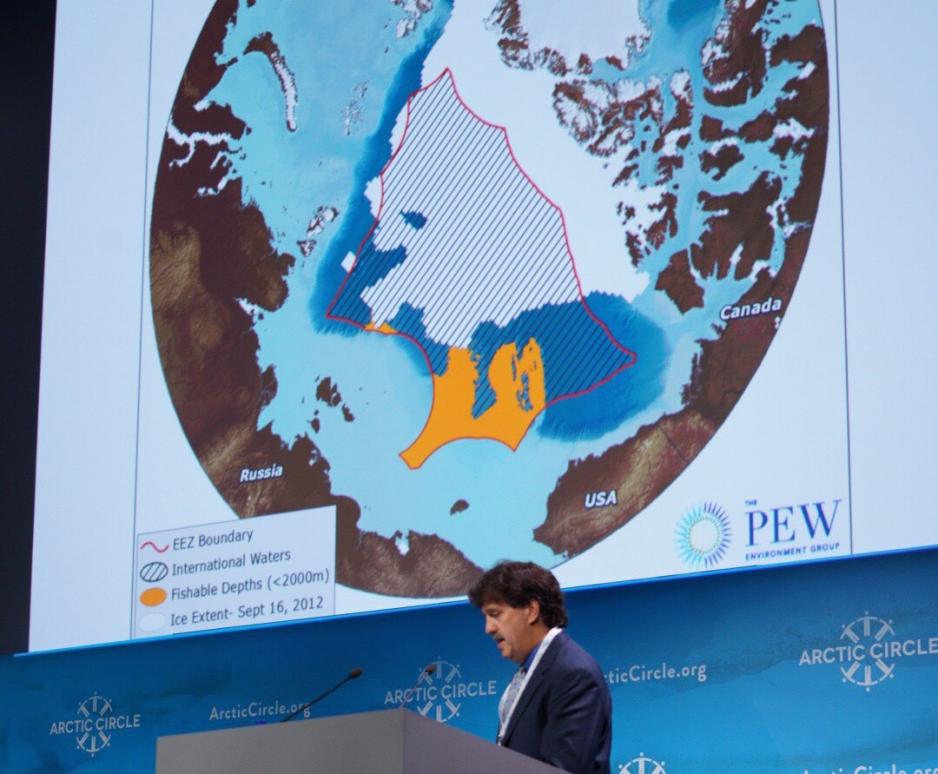

Currently, there are not enough fish to support commercial fishing in the central part of the Arctic Ocean, an area known as the ‘donut hole’ because it is encircled by the 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zones of Canada, Denmark (via Greenland), Norway, Russia and the US.

Fish migrate north

But as waters warm, scientists expect fish species to migrate north, as has been seen in northern parts of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Should fish arrive, receding ice will give fishing vessels greater access to an area of high seas the size of the Mediterranean Sea.

The search for a moratorium that includes non-Arctic states comes after America, in 2010, unilaterally banned commercial fishing in the waters north of Alaska. Other Arctic coastal states made a similar pledge by signing the 2015 Oslo Agreement.

The concern among Arctic states, however, is that without an agreement that includes countries with other large fishing fleets “vessels from other countries could fish at mile 201”, Mr Balton said.

Gather information

By drawing up a moratorium before fishing begins, the parties involved, which also include China, Iceland, Japan and Korea, want to give scientists the chance to gather information to allow for the establishment of a regional fisheries management organisation.

“We don’t understand the ecology well enough to allow fishing to begin,” Mr Balton said.

Conservation groups welcomed the efforts to establish regulatory measures before fishing begins, but some said permanent protection was needed.

High level of uncertainty

“An agreement where fishing in the warming and previously un-fished waters of the Central Arctic Ocean is on the table is not enough to ensure that this ecosystem is protected for future generations,” said Magnus Eckeskog, a spokesperson for Greenpeace.

He argued that climate change had resulted in a “high level of uncertainty” about Arctic marine ecosystem health, and urged Arctic states to instead support efforts to establish a maritime sanctuary.