Late-forming Chukchi sea ice continues unprecedented trend

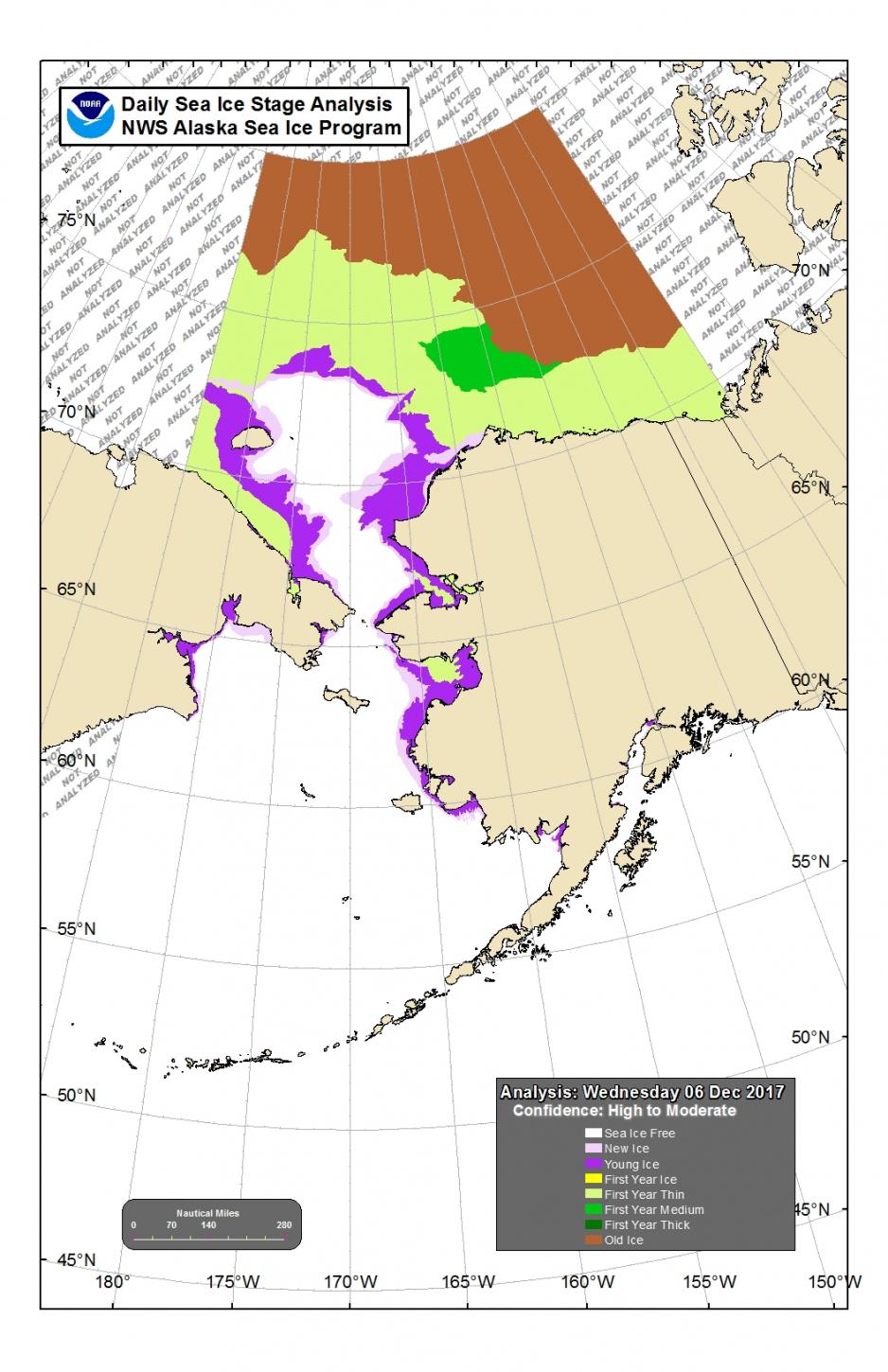

Sea-ice formation in the Chukchi Sea is nearly a month behind schedule, perpetuating a cycle that could see ice break up unseasonably early for the second spring running in 2018.

The slow development of sea ice is the result of “extremely warm temperatures” for November that rose to 6° C above average, according to Mark Serreze, the director of the National Snow and Ice Data Centre, a Colorado-based research outfit.

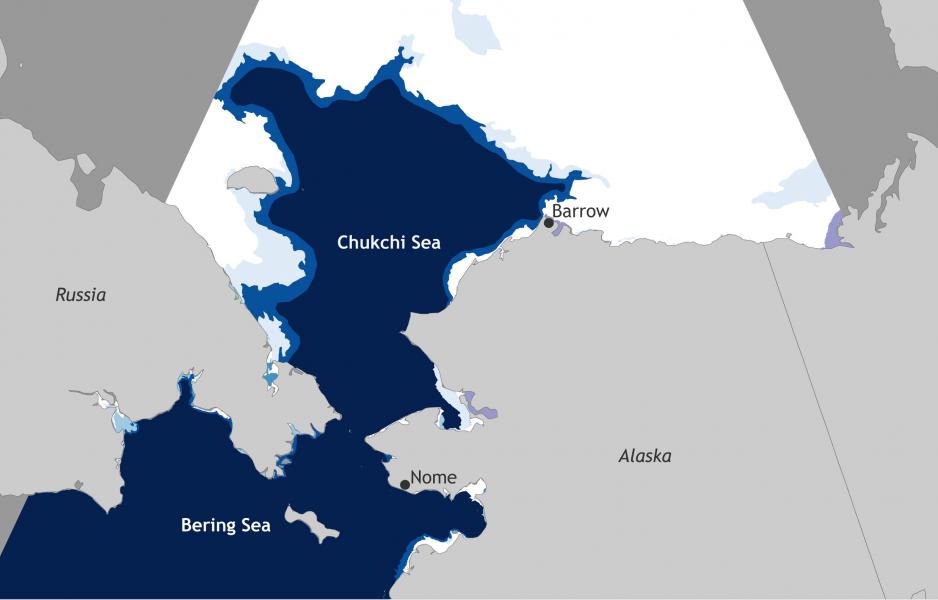

Those high temperatures combined with southerly winds to restrict ice cover to less than half of the waters off north-western Alaska. The extent is a record low for a time of year when sea ice should cover 90% of the Chukchi Sea, the NSIDC reported on Wednesday

“We’ve never seen a situation like this,” Mr Serreze said.

Overall, sea-ice coverage in November in the Arctic Ocean was the third-lowest ever recorded for the month.

This autumn’s lack of ice in the Chukchi Sea can be tied to an early break-up in the spring, when ice made fragile by warm winter temperatures and was cracked by northerly winds and driven into the Bering Sea.

Later, an influx of warm water drove ocean temperatures up to as much as 3° C above average. It is likely this higher water temperature that is preventing ice from forming.

“There is likely a considerable amount of heat remaining in the top layer of the ocean, which will need to be lost to the atmosphere and outer space before the region becomes fully ice covered,” the NSIDC wrote.

Yesterday’s announcement mirrors the language used by the NSIDC in June, when it reported a record-early retreat of sea ice in the Chukchi Sea. By third week of May, an “unprecedented” amount of open water for that time of year that had reached as far north as Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow), its report states.

Part of the explanation for the early and rapid retreat of sea ice was the high air and water temperatures the preceding winter.

Human activity, such as hunting and transport, can be expected to be affected by the current conditions through next spring, as any ice that does form will likely be less stable and may again disappear early if temperatures continue to remain above average, Mr Serreze suggests.

On land, the lack of ice has been tied to coastal flooding and erosion events that occurred in October and November. The open water itself may exacerbate the situation by exposing the air to warmer water, resulting in higher temperatures, more heat-retaining clouds and storms.