Commentary: The Arctic’s Nearest Neighbours: From High North to Northern Highlands

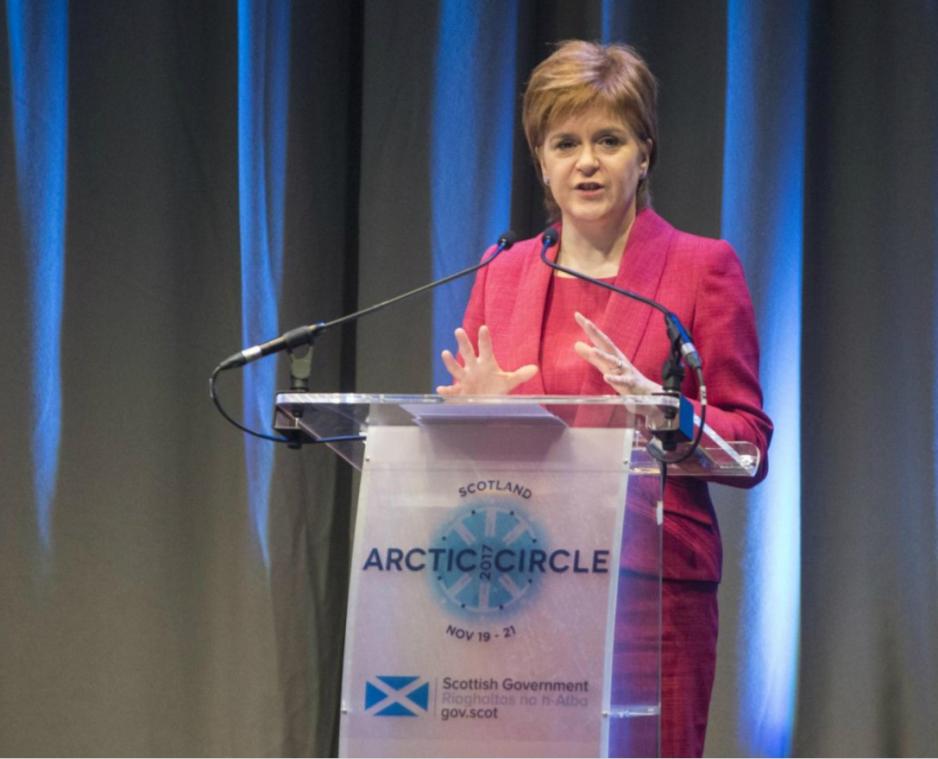

Scotlands First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, stressed the need to act decisively on climate change during her opening spesch in Edinburgh. (Photo: ACF Scotland).

In Edinburgh as elsewhere, it is the season for reindeer, snowflakes, and even a traditional Norwegian Christmas tree shining LED-bright. However, Scotland is directing attention northwards for more reasons than the upcoming holidays – for reasons that have to do with old relationships across the seas, with “near-neighbours”, and with the changing Arctic.

This week saw first ever Arctic Circle Forum Scotland take place in the heart of Edinburgh under the heading of “Scotland and the New North”. It attracted participants from both near and far – even from the far south, London – representing a wide range of societal sectors.

The Arctic Circle Forums are events co-organised by the Arctic Circle Assembly and local partners across the world. The Assembly itself is, in brief, an organisation initiated by then-President of Iceland, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson in 2013. At the time, many speculated whether it was a response to Iceland’s exclusion from discussions among the five Arctic coastal states in 2008; however, the organisation has today grown to stand on its own as a significant annual conference on the Arctic calendar. Every autumn, it brings Arctic stakeholders together in Reykjavik to talk Arctic business, policy, and research.

In 2016, First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon attended the Reykjavik Arctic Circle Assembly herself. There, she spoke powerfully of northern linkages across seas, of shared challenges, and of a “desire for even stronger partnerships with our northern neighbours”. A year later, the Scottish Government welcomed visitors to an Arctic Circle Forum in their own capital. Similar events have been held in Greenland, Singapore, and Washington D.C. – and upcoming ones include the Faroe Islands and South Korea.

First Minister Sturgeon spoke both to local Ministers of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) and Arctic visitors when she, in her opening speech, stressed the need to act decisively on climate change. Here, Scotland has positive experience to share, but also plenty to learn from fellow northern neighbours. As she pointed out, Scotland is the Arctic region’s nearest neighbouring nation.

Geography came up not only in Sturgeon’s speech, but was a theme that seemed to run through the conference. If an image speaks a thousand words, a map tells a whole story. From shipping companies that illustrated new sea-routes as smooth-running tube-like diagrams to evocative videos that drew shining lines from coasts and continents, maps were ubiquitous. If the future is northern, the UK’s northernmost nation sees itself as playing a part.

And indeed, for the occasion a new map had been drawn; one where a circle – not unlike the nominal Arctic Circle, as one might expect – was repositioned to pivot from somewhere on the Kangertittivaq fjord in eastern Greenland. Unlike the latitudinally defined Circle most often displayed, this placed Iceland well within the cool blue lines, with Scotland and Norway at equal distance from it. To the amusement of the audience, however, the small Faroe Islands had somehow disappeared from the event’s logo – despite their otherwise active role at the Forum.

While the title, the “Arctic Circle”, would suggest a circumpolar scope, the event was undoubtedly focused on the European North, and especially the West Nordics: Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands. As three small countries with varying levels of independence – Iceland of course being a fully sovereign state since 1944 – the alliance between them is about much more than geographical proximity. It is about having a voice in the international arena that is heard, about shared challenges as Atlantic island states, and about carving out their own national futures when global “periphery”, the Arctic, has suddenly become central. In contrast, and contrary to many similar Arctic events, Canada, US, and Russian participation was low if at all existent.

Former Icelandic President and Chairman of the Arctic Circle Assembly Ólafur Grímsson presented an Arctic welcome to Scotland as he opened the event in Edinburgh’s Assembly Rooms. Reflecting on his own personal encounter with Glasgow in his youth, he emphasised both the dramatic change that has taken place since and the enduring ties between the peoples. No doubt, his message of cooperation and connection was well received at a time when news-headlines are dominated by the opposite – difficult debates on divorce settlements under the banner of Brexit.

Although Brexit was not a focus in its own right, it remained never far below the surface. As Scottish politicians such as MSP Alasdair Allan pointed out, the Scottish population in fact voted to remain in the EU – in contrast to the southern majority. Given Iceland’s withdrawal from accession negotiations in 2015, Greenland’s lack of membership despite their enduring relationship with Denmark, and Norway’s ‘model’ relations with the EU, there was of course plenty more to be discussed than that strictly above 66°N. However, as Allan also pointed out, it was a welcome change to be addressing fellow politicians without having to bring up the dreaded B-word.

This is a time when it is more important than ever to be working together, seemed to be a message that resonated across speakers during the two days. A recorded video message from Brussels showed European Commissioner for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Karmenu Vella reassuring the audience that the EU would support their northern neighbours – without further specification. Representing the current Arctic Council Chairman-state, Finland’s Samuli Virtanen addressed the British in the room directly: “Even though the UK is leaving the EU, we hope you are not leaving Europe and the Arctic cooperation”.

The two days in Edinburgh saw not only high-level politicians speak about new “challenges and opportunities”, however. From Arctic Norway, Ole-Anders Turi represented the International Centre for Reindeer Husbandry. His main message, he summed up, was that engaging in the Arctic means engaging with the people there. And from Arctic Greenland, the postgraduate student Tukumminnguaq Nykjær Olsen gave a powerful presentation on the importance of education – and education on the terms of local communities, not of curricula-designers in the faraway Danish capital. And, from Scotland, the young research and design collective, Lateral North, showcased exciting work with Alaskan communities on mapping belonging and imaginations for the future.

The event also provided an opportunity to showcase new design, technology, and business. With sessions that were structured by sector, this meant that discussions of climate change were often separated by coffee and cake from transportation companies, eager to make use of new transpolar routes. Although there was little room for interactive discussion, no amount of sugar and warm drinks kept the audience from presenting the tension between these discourses to some of the speakers. And indeed, a session on environments and science left no doubt about the UK’s crucial contributions to knowledge on e.g. climate, ice-dynamics, and changing flora and fauna.

In the end, it was perhaps less clear why the North is “new”, but rather clearer that its future, however defined, will certainly require some new thinking. This means building relations, maintaining ties, and extending inclusive practices beyond latitudinal borders. Arctic neighbour, and most certainly “northern”, Scotland has much to contribute in an ever more global region.