Comment: - Put up or shut up with your Arctic conflict theory

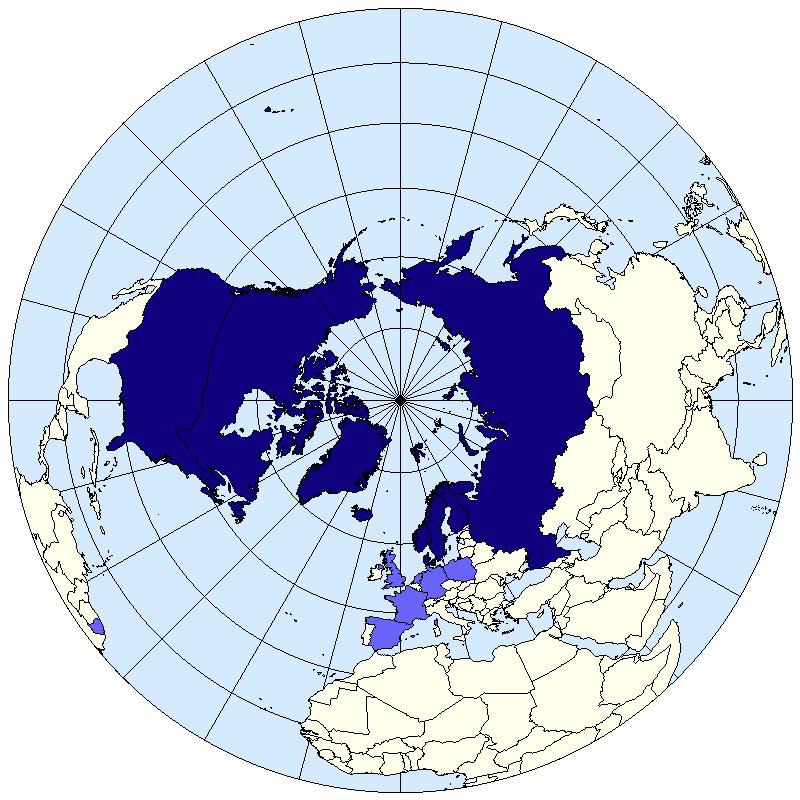

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has several times mentioned that China is not even a “near-Arctic state”. (Map from the Arctic Council).

The Arctic is on the verge of conflict, so the theory goes.

Melting ice is uncovering a trove of riches, we are told, and Putin feels entitled to all of it. Imagining the Arctic is somehow immune to the conflicts the West is embroiled in with Russia in other regions of the globe is wishful thinking. The Bear is increasingly armed and dangerous.

This is the narrative the media and some commentators have subjected us to for the past eight years, and the crisis in Ukraine has exacerbated the trend. It has taken on a life of its own, to the point where the premise of a race for the Arctic is introduced almost as a prerequisite in stories on the Arctic region, without detail or foundation. Is it possible things are really so bad?

I will readily concede that tensions right now between Russian and the West are high, and rightly so. Yet the Arctic as a political region has remained relatively insulated from these broader events. There are good reasons to expect the generally cooperative atmosphere in the Arctic to continue; there are only flawed reasons to think it will devolve into conflict.

Cooperation > Conflict

The past year has been a watershed in Arctic regional governance, though it has gone much unnoticed. First of all, the International Maritime Organization successfully negotiated the mandatory Polar Code for ships operating in polar waters. Legally, this is the biggest thing to happen to the Arctic since the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. While it is not exclusive to the eight Arctic states, they were prominent stakeholders in negotiations, with Russia arguably having the most at stake, and the parties found common ground.

Speaking of UNCLOS, both Denmark and Russia submitted claims to an extended continental shelf on their Arctic Ocean side in the past year, in December 2014 and August 2015 respectively. The two claims were submitted according to outlined procedures, and are measured in their scope. It may take 20 years or more before the final boundaries are assessed and agreed upon; but given the hoopla that has surrounded the "scramble" for this Arctic seabed, the past year’s events gave every indication that in practice the process will move forward collaboratively and according to international law.

Third, the five Arctic coastal states -- Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia and the United States -- signed in July a Declaration Concerning the Prevention of Unregulated High Seas Fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean, agreeing to abstain from commercial fishing until or unless a regional fisheries management organization is in place to regulate it. Since there is no fishing in this part of the Arctic, and none is expected in the short or medium term, the agreement itself can be described as having mostly symbolic value, and could have been deferred with no practical consequences. This makes it particularly noteworthy in assessing the state of Russian and Western cooperation in the Arctic.

Last but certainly not least, the eight Arctic nations are set to establish an Arctic Coast Guard Forum next week, formalizing their commitment to cooperate at the operational level in the maritime Arctic. This is constabulary, not military cooperation, but it is a huge indication of two things: the urgent need for joint collaboration on Arctic maritime security and safety issues and the willingness of the Arctic states to cooperate in that domain despite differences elsewhere.

Arctic = Exceptionalism

The above events provide evidence of Arctic exceptionalism but do not explain it. What makes the Arctic different in international affairs? I have often observed that most proponents of an Arctic conflict scenario are experts on Russia. Experts on the Arctic assume a more stable environment because: geography.

What would conflict in the Arctic actually look like? No one has ever explained that to my satisfaction. People will vaguely discuss the possibility of conflict in the ‘Arctic,’ without even narrowing it down to a particular country. Where will this impending conflict take place? For what purpose? Under what circumstances? Such specifics are never given. All they can say for sure is it will be Russia.

As Canadian Chief of Defence Staff, General Natynczyk remarked in 2009: “If someone were to invade the Canadian Arctic, my first task would be to rescue them.” In the vast majority of the Arctic, there is nowhere to occupy and nothing to take. It is assumed that a conflict would be over resources; how one would “take” these defies explanation. And why Russia, which is sovereign over half the Arctic land mass and will soon inherit a roughly South Africa–sized chunk of continental shelf, would need to seize additional Arctic territory when it has exploited only a fraction of its own is beyond me.

Canada and Denmark will also reap a windfall, as would the US if it ever signs the Law of the Sea (Norway’s claim has been accepted but is smaller). These Arctic coastal states are like the cat that caught the canary and have every reason to preserve the status quo.

Capacity does not equal intent

But look, the pessimists will say: The Arctic is undergoing a military build-up. Russia is remilitarizing. What are all these assets for if not to engage in armed conflict?

I will admit my eyes glaze over when my colleagues start talking military assets. But this is what I’ve managed to absorb in the past few years. Arctic military exercises in the current, post-post-Cold war era have generally been of a defensive nature, including the huge Russian Arctic military exercise in March. As the Arctic opens up to greater human and economic activity, it is the obligation of the Arctic states to ensure they have the capacity to control, defend and provide stewardship of their respective territories. Most of the time observers are claiming there is not enough investment in Arctic security infrastructure to provide minimum levels of control, at least outside of Russia.

Russia is different

Here Russia is a different duck. Its military capabilities in the Arctic far outweigh those of the other states. This is primarily because its credibility in nuclear deterrence rests in it Northwest corner -- on the Barents Sea, a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. Thus Russia’s Arctic military investment is less about the Arctic and more about its nuclear power status. In addition Russia has the biggest, and as a whole busiest, Arctic, and a concomitant need to exert control over it. For international relations theorists, this points to a further argument for Arctic exceptionalism: Since Russia is the predominant power in the region, it has no need to rebalance the power structure and can be expected to work to maintain the status quo.

At any rate, it has never been explained to me what the right amount of military investment in the Arctic is. Are current levels alarming or struggling to keep up with a newly opened ocean? I don’t claim to have an answer, but if someone wants to argue it is currently too high I think a reasonable baseline should be proffered.

The burden of proof

I was asked, two weeks ago, to participate on a panel on Arctic politics for a radio show while at the Arctic Circle conference in Reykjavik, along with my colleagues Lassi Heininen and Becca Pincus. (Disclosure: Alaska Dispatch News publisher Alice Rogoff is a co-founder of the Arctic Circle.) In my pre-interview with the producer, it became clear to her that I thought the Arctic was a pretty good model for international cooperation and didn’t expect any conflict in the foreseeable future. Would everyone on the panel feel that way, she asked? Yes, I expected so. Could I think of anyone with a contrary opinion? I ran through the list of my twenty or so colleagues in the field of Arctic geopolitics presenting at the conference. No one comes to mind, I apologized. (They did eventually find a contrarian view -- from a Russian expert).

Later on, as I sat through the Russian country session at the conference, where Arctic stalwart, Artur Chilingarov, affirmed that “there were no problems in the Arctic that could not be solved with words,” and Senior Arctic Official, Vladimir Barbin, articulated Russia’s commitment to “peace, stability and constructive dialogue in the region,” I pondered. Why has the burden been on proving a negative, that Russia will not start a conflict in the Arctic, when there has not been armed conflict in the Arctic for 75 years?

A new rule

Cooperation is the status quo. The Arctic is resilient to outside geopolitical forces and it is stable. I have been accused of being an optimist for touting these views, but I would counter that I am the realist; people who can’t accept the evidence for what it is are pessimists.

And so I propose a new rule: Those who submit that the Arctic is at risk of conflict must accept a higher standard of proof in showing how this would be so. They must be specific, and provide likely locations, assets, actors and circumstances.

They must explain why it is naïve to expect a lack of conflict in a region that has seen none for 75 years. And they must explain not only how Russian could, but why Russia would provoke conflict in the Arctic. I might also call for a ban on the headline “New Cold War’s Arctic Front” and its iterations, which is so overused as to border on the absurd. But I am afraid that would be pushing my luck. As it is, I know of only one author capable of meeting my first challenge.

Alas, Tom Clancy is no longer with us, and can not write that novel.

Heather Exner-Pirots comment first appeared in Radio-Canada’s Eye on the Arctic.