Op-ed: Brahms' Fourth Symphony in Post-Institutional Era: “Okay, Let it Be as You Wish”

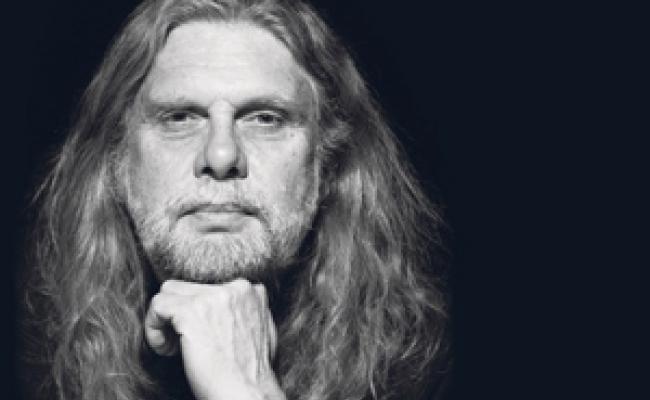

On March 16th, 2022, the Russian flag was lowered and removed from its staff outside the Council of Europe headquarters in Strasbourg. (Photo: Eda Ayaydin)

The opinions expressed here belongs to the author and do not represent the views of High North News.

Last Saturday, a friend of mine, who taught me to listen to Brahms through a Marxist lens - discerning the melodies of both the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, the West and the East - moved from his beloved Salt Lake City to Strasbourg, where he had just been appointed as the new Assistant Conductor of the National Opera.

To introduce this talented artist to both the American and French communities, a small gathering was held, bringing together a diverse group of people.

My scholar friend, Hakan Schaerer, described this event as an example of "cultural diplomacy" - bringing together people who might not ordinarily cross paths, giving them the opportunity to meet, engage, and learn from one another.

Indeed, this op-ed is, in a way, the output of that evening. Conversations ranged widely, but surprisingly (or perhaps unsurprisingly), we found ourselves discussing the Arctic, Russia, and Europe.

This piece will begin with soft political matters (the more uplifting part of the story) before transitioning to high politics (the less fortunate side).

The striking similarities in Russia’s response to the CoE, OSCE and the Arctic Council.

After the Arctic Council’s pause in 2022, I’ve become specifically interested in the European Institutions such as the work of the Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and I have been meeting with practitioners to better understand their interactions with Russia.

The OSCE was established during the Cold War, when both the West and the East (USSR) sought dialogue and created this multilayered institution. However, in this op-ed, I will reflect on a conversation I had that evening with interlocutors from the Council of Europe (CoE).

Our discussion highlighted the striking similarities in Russia’s response to the CoE, OSCE and the Arctic Council.

On March 16th, 2022, I witnessed a highly symbolic moment when the Russian flag was lowered and removed from its staff outside the Council of Europe headquarters in Strasbourg.

It was a remarkable and poignant event that sparked many questions regarding the practical necessity and constructive role of institutionalism.

Also read (The text continues)

Despite this, the tension lingered, and by the time of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia had once again become a suspicious actor on the global stage.

The discussions within the CoE intensified. Some decision-makers believed it was crucial to keep Russia within the CoE, but the majority of European decision-makers and bureaucrats opposed its continued membership in both the CoE.

By the end of 2022, a letter from Sergey Lavrov to the Council of Europe confirmed Moscow's decision to leave the organization, which the Russian Federation had joined, in 1996, following Gorbachev’s 1989 speech in Strasbourg.

One might also recall the infamous Murmansk speech from 1987.

While the Council of Europe responded by stating that a formal withdrawal via telegraph was not possible, the Russian interlocutor claimed, “They pretended not to see Lavrov’s letter”.

In response, Russia refused to pay its fees

Through first-hand sources that I spoke with in an informal setting over a dirty martini (all of the information shared here is written with their permission and semi-official meetings were held afterward), I had the opportunity to learn the details about Russia's withdrawal from the Council of Europe (CoE).

After the annexation of Crimea, Russia faced penalties at the CoE, and its members of parliament were barred from attending Assembly meetings. In response, Russia refused to pay its fees to the CoE.

However, over time, after not paying for 2 years, the Council went into an economic crisis, negotiations took place, and the Russian parliament members resumed attending meetings in June 2019 and started paying their fees again in July 2019.

In any case, the CoE adopted a resolution on the cessation of the membership of Russia from the Council. This was followed by lowering the Russian flag and canceling the badges of Russian representatives on the same day.

With this move, the CoE essentially told Russia, "You didn't leave me; I didn’t want you." Therefore, the phrase "okay, let it be as you wish"[*] in the title refers to both sides’ semi-voluntary liar’s poker like game.

This recalls Moscow's declaration on the 10th of March 2022, regarding this decision: “Let them enjoy each other’s company without Russia.”

Also read (the text continues)

During my discussion with an interlocutor, it was mentioned that the COE platform was originally founded for peace, and if we desire peace, dialogue is essential. Beyond that, he expressed concerns that the CoE may increasingly fall under the control of the EU.

Thus, Moscow either chose to leave or the Council of Europe decided to sever ties. A year later, Russia also stopped paying its fees to the OSCE for 2023 and ceased attending parliamentary meetings in 2024, labeling the organization as anti-Russian and discriminatory.

Surprisingly, its abandonment didn’t receive coverage in Western media, and even these high-level interlocutors of the CoE hadn’t heard of it until our meeting.

Similarly, Russia's journey with the Arctic Council, like with the CoE, began 26 years ago and has followed a parallel trajectory.

The seven Arctic states decided to pause cooperation with Russia, although they did not terminate the relationship entirely, then they have continued to low-level cooperation.

Also read (the text continues)

In conversations with representatives from CoE, who were unfamiliar with the structure of the Arctic Council, they expressed that the idea of suspending relations and low-level contact would have been a much preferable option for CoE to fully severing them.

When Moscow opted to stop paying its fees, it was neither a unique case for the Arctic Council nor directly related to leaving the organization. In all these institutions, Moscow continues to assert its need for legitimacy and advocates for practical, efficient cooperation and relations.

The key question here is how to deal with an unpredictable actor. Maintaining relations with such an actor is challenging, not only in terms of balancing international relations but also managing public opinion and credibility of institutions.

Beyond the Arctic Council, excluding a key player that has historically been a game maker and game changer leads to increased homogeneity and security concerns in the region.

To address these concerns and ensure stability or low tension, it is clear that diversity among actors is necessary. In the Arctic, regional security areas range from environmental protection to resource exploitation and geopolitical interests.

NATO is not the right forum to address the climate change

If all these areas are filled with NATO, a mechanism that provokes Russia more than any other, how can it be effective in terms of deterrence or stability? Beyond its military role, NATO has recently extended its visibility into the climate change arena.

However, as Arild Moe pointed out at the Arctic Security Conference in Oslo on September 12th, NATO is not the right forum to address the climate change as a problem, and its role as a promoter of climate policies is not useful.

Regarding ongoing securitization, Arne Holm emphasized in his recent comment, ironically pointing out that the rise in liver pâté and potato prices holds greater importance in Oslo, urging a focus on strengthening civil society rather than viewing the region solely through security policies.

Cooperation in the Arctic is increasingly focused on security since February 2022. All seven Arctic states are, now, members of NATO, and the Nordic countries also have additional bilateral military agreements with the U.S.

Moreover, there are mini security or defense clubs, such as those among the Nordics. This reminds me Michel Foucault’s thinking; when everyone in a room looks alike, it’s as if no one is really there.

Also read (the text continues)

The worst-case scenario of escalating securitization and militarization in the Western Arctic is that this preparedness could provoke more Russian militarization, leading to a more irrational and unpredictable Russia under Putin.

It's a cliché, but often true: if there’s a gun in the scene, it will go off.

Therefore, maintaining not only institutions but also cooperation is crucial, if only to keep dialogue open. If one day the President of Russia is gone, the regime won’t change overnight.

So, while it may be premature to discuss the post-war or post-Putin landscape, it is more practical to focus on the efficient use of structures that have already been established.

This could happen at the Arctic Council level or through other forms of bilateral cooperation, such as the ongoing Norway-Russia fisheries agreements.

It’s not me, it’s actually you who’s wrong

We are most likely entering a post-institutional era, marking the end of the rise of power of international institutions established or evolved after WWII. It is now time to refocus on individuals, bilateral relations, and sub-national entities.

The example of Russia’s departure from the Council of Europe (CoE) reminded me of Trellevik’s article from two years ago on Kirkenes-Murmansk relations, where he wrote, “It’s not me, it’s actually you who’s wrong.”

He further adds that the relationship status is complicated, rather than simply cutting it off. This pattern repeats across three different institutions: relations break down, and Russia then refuses to pay its fees because it sees the relationship as being one-sidedly severed.

Russia’s refusal to pay is somewhat akin to allowing a thin scab to form -an attempt to restore a bit of balance to the situation.

From my discussions, observations, and what I’ve heard at different scientific gatherings, it’s clear that leaving Russia isn’t a straightforward gain. It’s not about dealing with a party you don’t know, but one you are compelled to engage with.

Also read (the text continues)

Meaningful connections matter far more than generic perfunctory interactions. It’s similar to Brahms's 4th Symphony, which is designed to leave you mentally exhausted and emotionally shaken, rather than offering superficial comfort.

Just like how art, music and science transcend borders, fostering deeper understanding and dialogue, such as in the rapprochement of Turkish-Greek societies, Northern Ireland- UK relations or in the post-genocide era in Rwanda.

Or, like the Ancient Greek Olympic tradition “ékécheiria,” the Olympic Truce embodies the Olympic spirit of peace and calls for a ceasefire during the Games. These events offer opportunities for nations to connect, sometimes even halting wars.

While such ideas may seem utopian, they were conceived in 776 BC - so why not imagine similar or better ones in 2024?

These creative, sportive and intellectual forms remind us that dialogue doesn’t always have to happen at the highest political levels; people-to-people connections are just as powerful for security concerns.

This idea became even more tangible during a random Saturday night party, where I had the chance to learn, reflect, and ultimately write this.

P.S: I’m not particularly fond of Strasbourg, but for visiting a city that symbolizes reconciliation and peace in Europe, witnessing the changes in major European institutions, and hearing Matthew perform at the Opera are more than enough reasons to go.