Op-ed: Caught Between Scylla and Charybdis in The Arctic

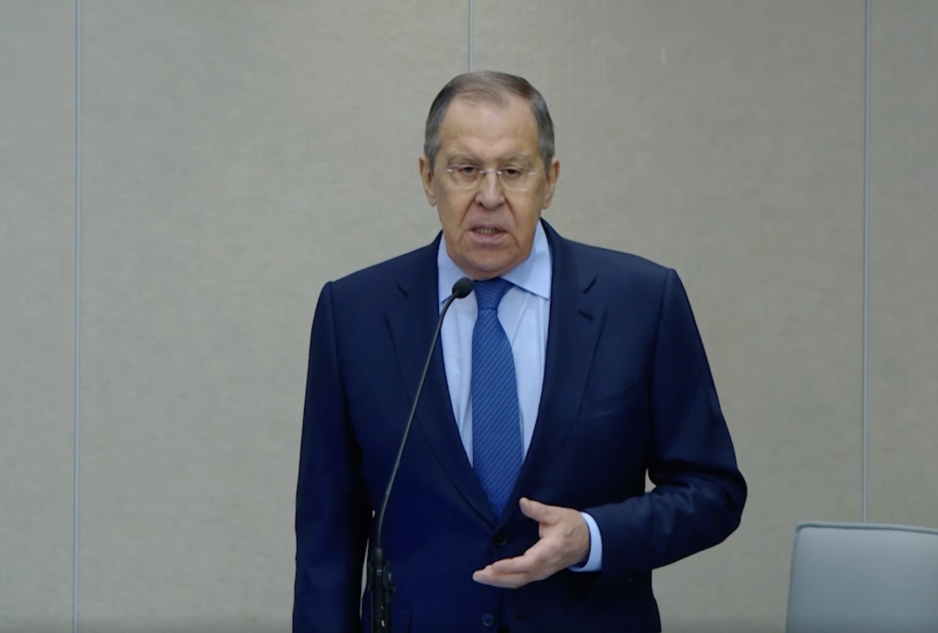

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has formally terminated the country's membership of the Barents Euro-Arctic Council. (Photo: Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

This is an op-ed written by an external contributor. The article expresses the writer's opinions. High North News is not responsible for the content of external links.

The Arctic is more than just a geographic region of the world. It represents the area from which the baseline of climate change, associated extreme weather events, and phenomena can be best understood. It informs and advises the planet’s governance and civilization.

Not long ago, Arctic nations cooperated in ways unmatched elsewhere and led the world in comprehensive climate change-related Earth system science.

Now, with geopolitical fallout following Moscow’s War in Ukraine, almost all Arctic cooperation with Russia has paused with no intent to resume in sight and scientific progress distressingly constrained and divergent.

In recent months, Russia has declared that it is prepared to withdraw from, or has already left, various Arctic-related institutions, including the Arctic Council (having already suspended annual payments), the Barents Euro-Arctic Cooperation (BEAC), the Fisheries Agreement with the United Kingdom, the Barents Fisheries Agreement with Norway, and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (following re-election failure to the IMO Council in Dec 2023).

It has also indicated that it will no longer support the International Space Station after this year and will not participate in a New START Treaty.

What is left is hard power

While many commentators assert that we should expect this kind of behavior from Russia, which is merely part of a campaign of rhetoric and complaining, Moscow is signaling otherwise.

Since the end of the Cold War, the West has sought to engage Russia through soft power mechanisms – efforts to attract and persuade – in regional and global institutions. This is neither feasible nor effective in a global order that Russia actively seeks to revise.

What is left is hard power – efforts achieved through coercion.

Moscow is highly cognizant of the Cold War and its decades of preponderantly hard-power competition. Add to that the authoritarian nature of the Kremlin regime and we should remember that this is Russia’s comfort zone.

The West may assume that its forms of coercion and soft power can contain Russia and prevail, but can it, and more importantly, is that the desired circumstances from which the West wants to compete?

Also read (the text continues)

Scientific cooperation remains the key to finding common ground and overcoming adversity through united efforts.

Without doubt, Moscow’s war in Ukraine remains absolutely abhorrent, but the need to scientifically cooperate with Russia on global-scale, climate change-driven crises and issues should necessarily remain a priority toward the greater good.

Science increasingly informs us of the best path forward to prepare and/or prevent what seems like a future of catastrophic doom. Justification to work together cooperatively exists, even if it requires consideration of working with adversaries.

Kevany considers the combined use of soft and hard power conducted via smart power as a means of understanding global health programs, which examines the use of “health-related cooperation to pursue non-health objectives’ in the foreign policy context.”

The same can be said of scientific cooperation, using scientific-related cooperation to pursue non-scientific objectives in the foreign policy context. Global health programs tend to continue despite geopolitics, and maybe it is time to elevate the importance of scientific cooperation to the same.