Old Conflict Reignited: 30 Year-Old Compromise Divides USA and Canada

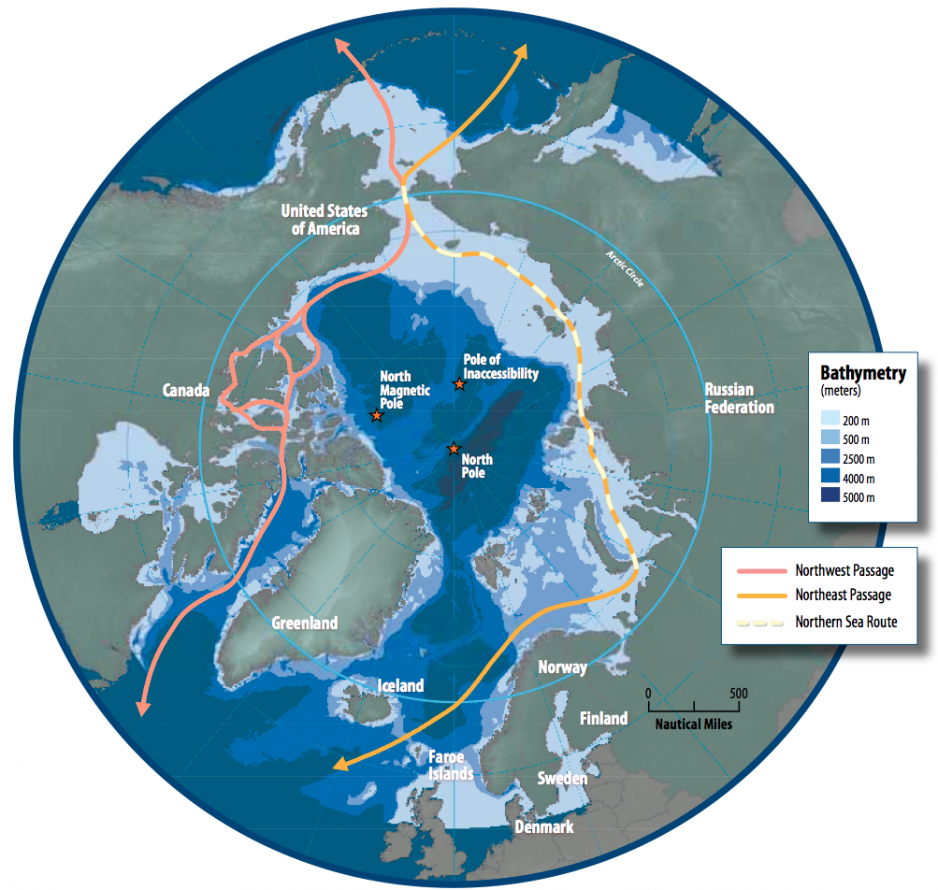

This map shows Russia’s long Arctic coastline and the Northern Sea Route (Northeast Passage) and the Northwest Passage. (Illustration: Susie Harder/Arctic Council)

For decades, the USA and Canada have agreed to disagree about who holds the rights to the Northwest Passage. However, the 1988 compromise now appears to be cracking at the seams.

The debate was revitalised following the American navy’s December 2018 announcement claiming freedom of navigation for shipping in Arctic waters.

Richard V. Spencer, Secretary of the American Navy, says the reason for this is that the US risks lagging behind what he describes to The Washington Times as “increasingly provocative moves by the Russian navy, in the scramble for control over what may be the globe’s last major unexploited region”.

Disagree on legislation

The USA argues that these areas are subject to public international law and that the USA thus holds right of innocent passage according to the UN Law of the Seas (UNCLOS). However, this argument does not hit home with the Canadians.

As late as during High North Dialogue in Bodø last week, P. Whitney Lackebauer, Professor at Trent University, made it very clear that Canadian authorities not will accept American transit through Canadian internal waters.

P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Professor at Trent University, made it very clear that Canadian authorities will not accept American transit through Canadian internal waters.

- It is not yet clear whether these assignments will be conducted to claim right of innocent transit through the Northwest Passage (Canada) or the Northern Sea Route (Russia). However, both Canada and Russia argue that these straits are subject to their full sovereignty, without right of transit, he stressed to the participants attending the Arctic Security Perceptions lecture.

His view is confirmed by the Canadian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Global Affairs Canada, which writes the following in a statement to High North News:

- Canada remains committed to exercising the full extent of its rights and sovereignty over its territory and its Arctic waters, including the various waterways commonly referred to as the Northwest Passage.

Fears diplomatic crisis

Lackenbauer’s statements came as a response from remarks from Mead Treadwell, who was Lt. governor of Alaska from 2010-2014. Treadwell describes oil and gas, shipping and military issues as “the three elephants in the room”.

- These three issues are more or less absent from the Arctic debate, he said.

Mead Treadwell, LT. Governor of Alaska from 2010-2014, described oil and gas, shipping and military issues as "the three elephants in the room” during High North Dialogue in Bodø.

This remark instantly lit Lackenbauer’s fuse:

- The American strategy is like holding your hand over the big red button, he said, and fears that it may evoke serious consequences.

– If the USA claims a freedom of navigation voyage through Canadas Arctic waters, this will cause enormous friction between our two countries. Not to mention: if the US undertakes a freedom of navigation voyage through Canada’s Arctic waters, this will certainly create tremendous political friction between our two countries. If the US Navy were to conduct a freedom of navigation voyage through the Northern Sea Route, Russia might see this as an act of war – which could have serious diplomatic repercussions and destabilize Arctic relations.

Global Affairs Canada describes the defense and security relationship between Canada and the USA as longstanding, well-entrenched and highly successful.

- The closeness of the Canada-US defence partnership provides both countries with greater security than could be achieved individually.

An old dispute

As previously mentioned, the debate about the Northwest Passage is far from new. And it is once again necessary to go far back in time to understand why the debate has flared up once again.

The Northwest Passage is a waterway meandering through Canadian waters, however, it is nevertheless the fastest and most efficient way for moving from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean.

As early as in the 1950s and 1960s, the USA claimed that the passage should be considered an international strait in accordance with the UN Law of the Seas (UNCLOS). However, Canada countered that since the route had never been actively used, it could not be claimed in the same way as for instance the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal – where anyone is free to pass through. They consider the Northwest passage Canadian waters with internal restrictions.

The USA wants freedom of navigation because that underpins the principle of free international trade, on which the US’ power and strength is built, and she is willing to go far to maintain that principle.

However, Canada fears that by opening up, they will lose control over what goes on in the High North.

The Northwest Passage is a rather meandering waterway going through Canadian waters, however, it is nevertheless the fastest and most efficient way for moving from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. As early as in the 1950s and 1960s, the USA claimed that the passage should be considered an international strait in accordance with the UN Law of the Seas (UNCLOS)

The USA has repeatedly demonstrated that it does not accept the Canadian view. The last time was in 1985, when the Polar Sea icebreaker was sent through the Northwest Passage without requesting permission, a move that evoked diplomatic shock waves on both sides.

The dispute was so intense that it made it to the agenda when American president Ronald Reagan and Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney met in Ottawa in 1987, more than a year later.

It was a meeting between friends, both of Irish descent, according to an article on priorg.com. The meeting is said to have been the inception of the following year’s compromise; a compromise meaning that the Americans shall always request permission before making a voyage through the Northwest Passage, however, that the Canadians shall always say yes.

Creates insecurity

- They agreed to disagree, says researcher Andreas Østhagen of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute and Nord University, who has conducted a lot of research on the geopolitical situation in the Arctic.

He says that the compromise has, by and large, been respected since.

However, the situation has changed dramatically since then. Due to climate changes and melting ice, the Northwest Passage has become available for other vessels than icebreakers too. The number of ships making the voyage has increased from 11 in 1988 to 47 in 2016, according to the Canadian Coast Guard.

Østhagen does not find the statements from the American navy shocking in and of themselves, as it is an overall current trend that ‘everyone’ wants to be present in the Arctic.

- However, the problem is that the Americans have not stated the goal and meaning of these operations. And, not to forget, where the voyages are to take place and who they are aimed at, he says.

He refers to similar operations elsewhere in the world, where the goal may be to fight pirates or to show off to the Chinese.

So what may be the reason why no details are provided regarding the goal and meaning with the Arctic operations?

Researcher Andreas Østhagen does not find the statements from the American navy shocking in and of themselves, as it is an overall current trend that ‘everyone’ wants to be present in the Arctic. (Photo: Malte Humpert)

- A conspiraty answer would be that the statement is a means to achieving a goal. A goal that could be creating insecurity. Another explanation may be that they do not really have a specific plan, or that the situation is related to a lack of understanding of the situation, the complexities of the High North and the sensitivity of the relationship with Canada.

He argues that both theories may fit well into the current American political landscape, with a strategy placing ‘America first’ and appearing somewhat hard-fisted.

Provocation?

P. Whitney Lackenbauer’s fear is shared by many. “The stakes are high on multiple fronts about control of critical new commercial shipping lanes is increasingly up for grabs through once-frozen Russian and Canadian trade routes” according to experts speaking with The Washington Times.

Gunhild Hoogensen Gjørv, provessor at UiT Norway’s Arctic University, said during the High North Dialogue panel dabeate that the believes it is about time we place the cards on the table and talk about the increasing militarization that can be observed in the High North.

While Ingrid Medby, who has conducted research on the various countries’ Arctic identities, fears that too much talk about the threats, for instance through NATo, will be counterproductive and potentially be interpreted as a threat in and of itself.

Andreas Østhagen would, however, not go as far as Lackenbauer and call it a provocation.

- So far, I consider it more of a warning. However, any conducting [of such a voyage] would constitute a provocation. And the situation we see now may be the beginning of a process that will wake a sleeping dog, he says in closing.

In a comment to High North News, the American embassy in Oslo writes:

The United States is committed to preserving the Arctic as a region free of conflict, where nations act responsibly and exercise their rights and freedoms in accordance with international law. The Arctic region has a long tradition of international cooperation, as embodied in the work of the Arctic Council. With the Arctic Council as the primary mechanism, the United States will continue to promote international cooperation and shared interests through its presence and engagement in the region.

From the left: Ingrid Medby, who has researched the various countries’ Arctic identities; Gunhild Hoogensen Gjørv, professor of UiT Norway’s Arctic University, P. Whitney Lackenbauer, former Alaskan governor, and Paal Hilde, Associate Professor at the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies.