Wildfires Ravage the Arctic

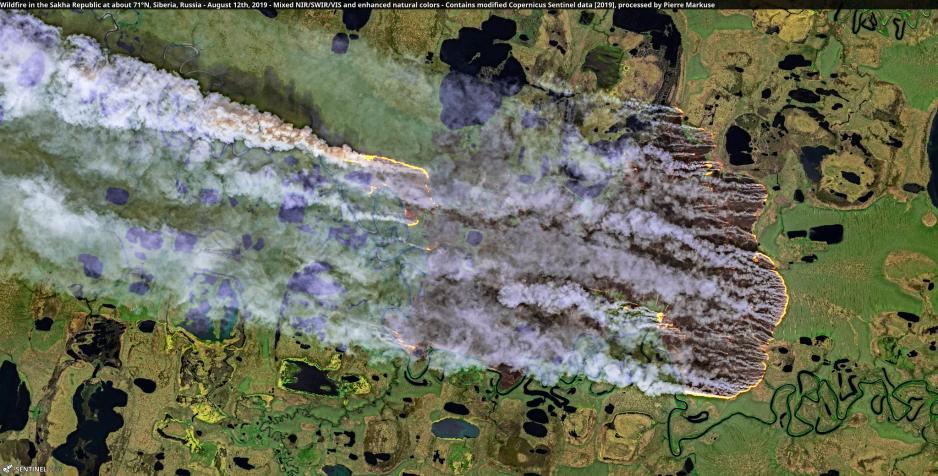

Wildfire in the Sakha Republic at about 71°N, Siberia, Russia. Picture from 12 August 2019. (Photo: Pierre Markuse)

The summer of 2019 has seen the worst Arctic wildfires on record, and climate scientists predict that it will only get worse in the years to come.

Since June, hundreds of wildfires across Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Russia have produced more carbon dioxide than Sweden’s entire annual emissions, according to the World Meteorological Organization, the United Nations’ weather and climate monitoring agency.

Fires in June were ten times bigger than normal, covering the largest area and producing the largest emissions on record, said London School of Economics associate professor Thomas Smith, who studies peat fires. Arctic fires in July were four times larger than normal.

Smith attributes the fires to several causes, but a major factor is soaring temperatures in the region, which has experienced its hottest summer season on record. The Arctic is warming three times faster than the rest of the world, causing temperatures to rise 8 to 10 degrees higher than average in June, Smith said.

Peat soil and carbon emissions

The Arctic fires are especially potent because their fuel is usually not typical forest materials, but peat soils. Peat is material found in bogs, which “has been accumulating for thousands of years,” said Mike Flannigan, a professor at the University of Alberta’s department of renewable resources and director of the Western Partnership for Wildland Fire Science.

“Peat soils should remain waterlogged all year round, but the extra heat this year has been enough” to dry them out and create fuel for fire, Smith said.

“Burning peat is releasing carbon that has been stored over 10,000s of years and is irreversible,” said Mark Parrington, a climate scientist at the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

Burning peat is releasing carbon that has been stored over 10,000s of years and is irreversible

In Alaska alone, the 2019 fires have burned an area larger than Yellowstone National Park and released three times more emissions than what Alaska emits annually from burning fossil fuels, reported the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Additionally, the fires cause rampant air pollution which is blown all over the world by wind. In Siberia, several large cities have reported significant drops in air quality, and northern fires in North America have produced pollution that was registered as far south as the Great Lakes Region, Parrington said.

Local Indigenous communities in Alaska have been on the front lines of the fire problem. “We experience terrible air quality in all our communities, affecting people’s health and quality of life. We have had some serious impacts on the forests surrounding communities as well, with animals being driven away by the flames,” Edward Alexander, a member of the Gwich’in Council International (GCI), told the Arctic Council at the beginning of August.

Warming weather and positive feedback loops

According to Flannigan, three components need to be present for a fire to ignite: fuel, ignition (such as lightening or human activity), and hot, windy and dry weather. Weather is undoubtably the biggest influence, and warm temperatures are more conducive to lightening, which has become more common in the Arctic. If all three components are present the fire can be self sustaining and last for months.

Some fires can smoulder in the peat even when the ground is covered in snow in the winter, Flannigan said, resurfacing in the spring once it gets warmer, and lasting multiple years at times.

While the Arctic has seen summer wildfires on a fairly regular basis in recent years (though they were considered quite rare until 2007), this year is “unprecedented” in the amount of wildfires, their size, and their location in the far north, said Smith.

“The fires are at a scale and intensity that makes them almost impossible to fight directly,” he said. “Fires at lower latitudes are driven far more by human ignitions and land management strategies, so there are more options; but these fires are driven by weather and lightning (meaning beyond human control).”

The remote location of the northern fires makes them dually difficult to deal with, because in most Arctic states, there is limited infrastructure in the areas affected. In Canada, Flannigan said, the fires are normally left to burn unchecked unless they approach something of “societal value” such as a town, a mine, or a pipeline.

This year is “unprecedented” in the amount of wildfires, their size, and their location in the far north.

The fires are also exceedingly difficult to fight given their size. When they are smaller than a football field, they are relatively easy to put out with experienced firefighters, but if they become larger and it’s hot and dry out, trying to manage them is like “spitting in a campfire,” Flannigan said. “You’re wasting your dollars.”

Nonetheless, in Russia, the military has been called in to help fight dozens of massive fires, some of which are 700 to 900 kilometres squared, whose smoke can be seen from space.

The prognosis is not good – scientists believe the issue with repeat itself in the future, “if the fire conditions continue to be warmer and drier in the Arctic,” Parrington said.

Hotter weather dries peat soils out more, which produces more fires, releases more carbon, and contributes to the warming world, which in turn creates conditions for even more fires, creating a positive feedback loop, said Smith. “All these emissions from these peat fires will only contribute to more warming, which will contribute to more peat fires.”

Flannigan estimates that greenhouse gases released from the fires are “quite significant” on a global scale. “There could be some nasty surprises in the future,” he said.