Constructing Arctic Identity: Analysis of Scotland’s Arctic Policy

What remains not so evident is what Scotland wants from the Arctic in return for its offer in the long run, writes Alexandra Middelton.

By: Alexandra Middleton.

Scotland launched its Arctic Policy Framework on 23 September 2019. The whole project has been long in the brewing starting from active engagement in the Arctic Circle conferences since 2016 where Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon outlined Scotland’s ambition “to build closer alliances with our northern neighbours”. The Scottish delegation to the Arctic Circle conference in 2017 included 313 (15% of all participants) [1] representatives of government, businesses and other stakeholders.

Newly published Scotland’s Arctic Policy 2019 is a long-awaited culmination of Scotland's effort to have its say on the Arctic arena. The policy document was developed with support from the Arctic Steering group comprising Orkney and Shetland Islands, representatives from St Andrews University Arctic Centre, the European Policy and Research Centre, Scottish Association of Marine Science and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. Several stakeholder outreach events took place in the course of policy formulation.

About the author

Alexandra Middleton is an Assistant Professor in Financial Accounting at Oulu Business School, University of Oulu.

Her areas of expertise include sustainable business development, human capital, innovations and connectivity solutions in the Arctic.

She is a member of the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) Task Force on Climate-Related reporting.

Map symbolism

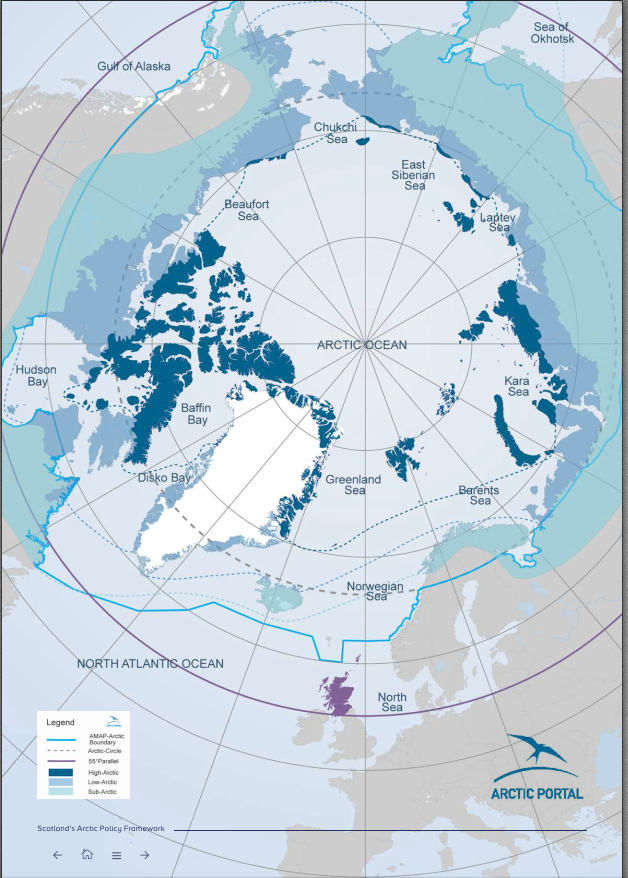

The second page of the document presents a map of Scotland from the Arctic perspective. The usage of the map as a starting statement in the policy document uses the map’s pervasive communication power. Maps have long served as powerful tools per se to legitimize interests[2] . In its own words “Scotland is reshaping the map. Rather than geographically peripheral at the north-west corner of Europe. Scotland is strategically positioned-and has the capability- to serve as a link between the Arctic region and the wider world”. Different borders displayed on the map suggest the fluidity of the Arctic definition and reinforce Scotland’s message of being geographically the Arctic’s nearest non-Arctic neighbour.

Elements of Arctic identity

The policy document which is 46 pages long, is easy to follow and is full of positive examples and nine case studies. Scotland calls itself a “good Global citizen” that is ready to build bridges. Nearly half of the document is devoted to explaining why Scotland has historical connections to the Arctic. Mythical construction is a representation of the past which is linked to the establishment of identity in the present[3]. Elements of the Arctic identity are numerous in the document, starting from an array of historical and geographical links, town names in the Highlands and Islands that can still be traced back to Nordic roots, language linkages, people of Scottish descent living in the Arctic countries. Finishing with stories of heroism of the Arctic explorers of Scottish descent. To draw a parallel the policy uses challenges such as health and wellbeing in rural communities and connectivity problems that the Arctic countries and Scotland are facing. Furthermore, belonging is emphasised by Scotland’s’ participation in the EU-funding and research projects with the Arctic countries.

The belonging to the larger Arctic community is exemplified in the areas of Education, Research and Innovation, Cultural Ties, Rural Connections, Climate Change, Environment and Clean Energy and Sustainable Economic Development. The message is conveyed via a positive prism, statistics are selected to demonstrate phenomena in a favourable light.

While China considers itself “a near-Arctic state”, Scotland promotes its credentials as “a key near-Arctic marine transport and logistics partner".

The policy borrows neologism introduced by China’s Arctic White Paper. While China considers itself “a near-Arctic state”, Scotland promotes its credentials as “a key near-Arctic marine transport and logistics partner”.

Sustainable economic development

In the sustainable economic development section, the policy outlines examples and some future pathways related to trade and investment links, shipping and ports, oil and gas, sea fisheries, aquaculture, international connectivity and data centres, space industry, land and marine planning.

What the strategy is silent about is the predominantly Norwegian multinationals ownership of 226 active fish farming sites, stretching down the West and North coast of Scotland. Scotland is the third largest Atlantic salmon aquaculture after Norway and Chile. The controversy stems from the damage to the ecology of inshore sea lochs caused by aquaculture in Scotland[4]. The aquaculture industry intends to double its production by 2030 to between 300 and 400 thousand tonnes per year[5]. Increased environmental impact of aquaculture expansion requires clear rules of the game and societal acceptance of the industry potentially harmful to the ecosystems.

The policy states that “domestic oil and gas industry can play a positive role in supporting the low carbon transition, in terms of transferable skills and infrastructure”.

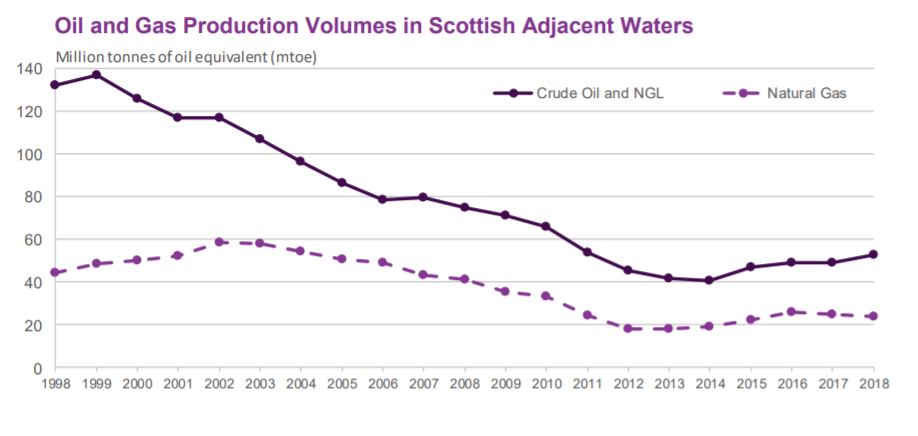

Like in other Arctic countries oil and gas industry constitutes a large proportion of GDP in Scotland (9%), compare to 22% and 30% in Norway and Russia respectively. There are 252 oil and gas fields in operation in Scotland[6] and production of crude oil and natural gas liquids (NGL), which account for around two-thirds of the total, increased by 8.5% from 2017 to 2018, while extraction of natural gas decreased by 3.1%[7] Still the production of oil production decreased by nearly 60% from 1998 (see Figure 2).

The policy mentions fuel poverty and some initiatives how to combat it. Scottish people pay for their electricity bills 7-9% more than Great Britain’s average[8]. The policy discloses that 100,000 people are currently employed by the oil and gas sector. Issues to consider in the future are sustainability of the oil and gas industry, and potential job losses affecting Scottish population.

Offer to the Arctic

The last section of the policy is clear and straightforward where Scotland declares its offer to the Arctic. The biggest take is establishment of an Arctic unit within the Scottish Government’s directorate for External Affairs and creation of a fund to support projects and activities promoted by third sector and community organizations that raise awareness of Scottish-Arctic links and create new opportunities for international collaboration with the Arctic.

Neither timeframe for Arctic unit nor the sum allocated to the fund are specified in the document. The policy is articulate about cultural ties, education, research and innovation links and Scottish know-how that can be beneficial for the Arctic countries.

What remains not so evident is what Scotland wants from the Arctic in return for its offer in the long run.

What remains not so evident is what Scotland wants from the Arctic in return for its offer in the long run. The policy does not mention the Arctic Council or Arctic Economic Council as mediums for cooperation and Scottish involvement in the Arctic matters. Time will tell the acceptance of the Scottish Arctic identity by the world. We are yet to see how much of the policy aspiration will spring to life and how much remains merely as a beautiful to read document.

Sources:

[1] Source: https://www.gov.scot/publications/foi-17-02746/

[2] Barton, B. F., & Barton, M. S. (1993). Ideology and the map: Toward a postmodern visual design practice. Professional communication: The social perspective, 49-78.

[3] Friedman, J. (1992). Myth, history, and political identity. Cultural anthropology, 7(2), 194-210.

[4] https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-48266480

[5] http://scottishsalmon.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/aquaculture-growth-to-2030.pdf

[6] https://www2.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Economy/oilgas/Methods

[7] https://news.gov.scot/news/oil-and-gas-production-increases-4-6-percent-in-2018

[8] https://www2.gov.scot/Resource/0053/00531699.pdf