Arne O. Holm says The War Creates “Optimism” in the Arctic

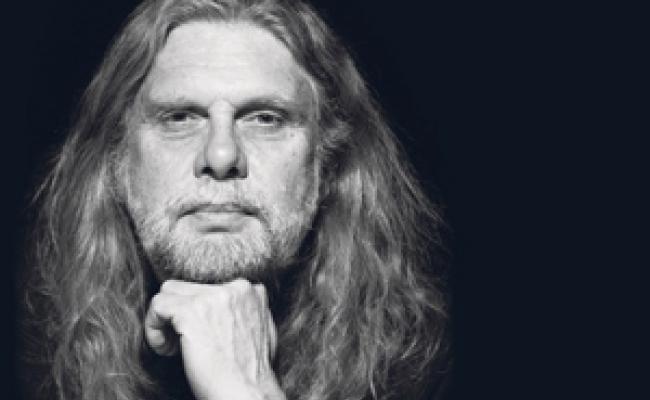

Olafur Ragnar Grimsson in conversation with Adnan Z. Amin during the Arctic Circle Business Forum in Reykjavik, October 2024. (Photo: Arne O. Holm)

Comment, Reykjavik: "Innovation is the fuel of tomorrow. Not oil and gas." Adnan Z. Amin looks out over an audience of business people in Reykjavik, Iceland. The topic is investments in the Arctic. Over the next few hours, several speakers will emphasize that the war in Europe provides new opportunities.

This is a comment. All opinions and perceptions are the author's own.

The Arctic Circle conference in Iceland is a melting pot of people from all over the world queuing up to hear the latest news about the Arctic. Most of what they will hear are old news.

Perhaps that is why the conference has birthed an offspring named "Arctic Circle Business Forum," a more tailored conference product aimed at an audience with more capital in the bank than all the world's researchers can come up with.

The academics oftentimes don't create other workplaces than their own, which are usually funded by the public.

Own playroom

Therefore, the neighboring hotel of the culture house Harpa, where the actual conference takes place, is a far less crowded location. The hunt for Arctic investors has always been an important part of the Arctic Circle conference.

What is new is that business has received its own playroom.

Innovation is the fuel of tomorrow.

And this is where Adnan Z. Amin sends his clear message to states that continue to invest in oil and gas.

As the CEO of the UN's climate change conference COP28, he adds weight to his statement by referring to the climate conference's declaration.

"The aim of reducing oil and gas has never before been part of a declaration," he says and adds:

"A renewable revolution is taking place."

If he and the UN are right, this is the beginning of the end of the oil age. Those who still wonder why the Norwegian currency is at a bottom level, while interest rates are still high, do not need to look further for an explanation.

Fertram Sigurjònsson has created a billion-dollar business in a small town in Iceland. Here he is at the Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavik. (Photo: Arne O. Holm)

The question is, then, who and what will invest in the Arctic?

I snuck into the business conference, looking for answers. The hotel where the conference is taking place is itself an example of how money finds its way to the Arctic.

The hotel was a giant hole in the ground for a long time before US expertise and capital entered the field and finished a building worth many billions.

Tourism with foreign ownership is, in other words, still hot in the Arctic.

Batteries are out

The same can be said about the hunt for raw materials, although future investments in mining will be quite different.

I snuck into the conference.

Investors are focusing their interest on so-called rare-earth metals, minerals necessary for all modern electronics. Those who want to gather capital to open a new iron ore mine will have to look hard.

Hydrogen has long been the answer to a green shift, not least within the transport sector.

If we are to believe those who claim to know about these things, that is hardly the case anymore. Hydrogen as a fuel is expensive to produce and expensive to transport. In the future, its use will be limited to relatively local industry production.

Battery production, which was the answer to almost everything, not least in Norway, is not even mentioned by investors.

Something new, that paradoxically creates optimism in the Arctic, is Russia's war against Ukraine. It establishes both room for industrial growth and optimism.

Both Benedikt Gislason, CEO of the Icelandic bank Arion Bank, and Matz Q. Frederiksen, Director of the Arctic Economic Council, have defense and military industry on their list. Without mentioning the war.

Fish skin

And precisely that point is underlined by an international wave of stock speculation in the arms industry.

During a break, I perform a rough and informal analysis of where and in what the large equity and buyout funds are currently investing. The portfolios rarely point toward the Arctic and the High North.

Except when it comes to healthcare.

Almost as an answer to my investigations, a real founder suddenly appears on the stage. Fertram Sigurjònsson comes from Isafjordur, an Icelandic fishing village with just under 4,000 inhabitants.

In the village, he built a company that uses fish skin to treat people who have had to have a leg or an arm amputated. He found the raw material right outside the front door.

Last year, Kerecis, as the company is called, was sold to Coloplast, an international company with more than 12,500 employees. The sales total was a staggering 1,2 billion dollars.

Or as Adnan Z. Amin put it: Innovation is the fuel of tomorrow.