Op-ed: UNESCO Celebrates the Start of the Decade of Indigenous Languages - But What Will it Mean for Scotland and the Arctic?

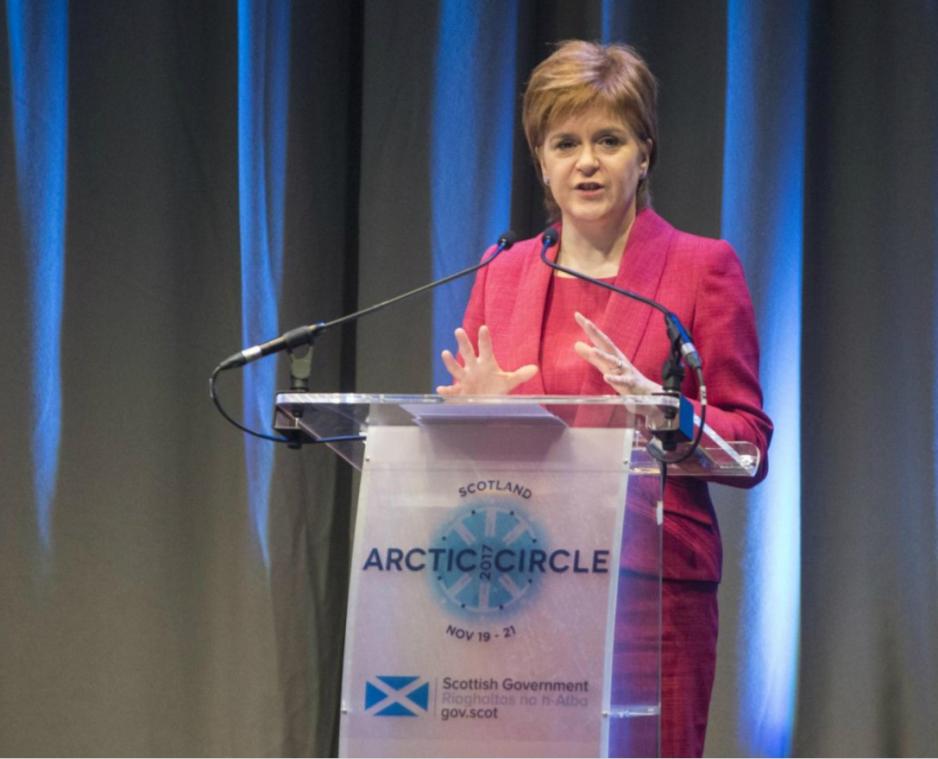

Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister of Scotland, reminded her audience that Scotland is the “most northerly non-Arctic nation” and highlighted Scotland’s growing partnerships with Arctic countries. (Archive photo from a Arctic Circle 2017: ACF Scotland)

The opinions expressed here belongs to the author and do not represent the views of High North News. High North News is not responsible for the content in external links.

The long-awaited International Decade of Indigenous Languages will start tomorrow. In a 2021 speech, Nicola Sturgeon, the First Minister of Scotland, reminded her audience that Scotland is the “most northerly non-Arctic nation” and highlighted Scotland’s growing partnerships with Arctic countries.

One need only to look at the many Scottish universities which are now part of the University of the Arctic network or the Scottish Government’s newly established Arctic Connections fund.

Only weeks ago at the Arctic Assembly, which is held in Reykjavík every year, the Vigdís International Centre for Multilingualism and Intercultural Understanding at the University of Iceland organised a session discussing the ten-year initiative.

The Scottish government outlined its support for the initiative a day later and even mentioned collaborating with Arctic partners via their Arctic policy framework and potential “opportunities to develop joint projects”. Could one of these include an interdisciplinary project on language revitalisation efforts with the psychological well-being of Scottish and Arctic communities in mind?

Indigenous languages and psychological well-being in the Arctic and Scotland;

Like many Arctic countries, Scotland has an indigenous language: Gáidhlig. However, very few Scots can understand the language.

The section on Cultural Ties in Scotland’s Arctic policy framework underscores the promotion and protection of indigenous languages as one of their priorities; they write “there is a great deal [Scotland] can learn from Arctic countries as to how they are supporting their own indigenous languages and dialects”.

This follows increasing Scottish attendance at Arctic Circle Assemblies.

In Rural Connections, the Scottish Government cites suicide rates in Scotland and Arctic countries as well as how both parties can cooperate to address these challenges. Interestingly, language revitalisation is associated with improved psychological well-being along with reduced rates of suicide and substance abuse (Grenoble in Revitalizing Endangered Languages).

Bórd na Gáidhlig, a Scottish organisation that promotes the revitalisation of Gáidhlig, recently responded to the Scottish Government’s consultation on A New Mental Health Wellbeing Strategy by emphasising the language’s role in strengthening confidence, identity and well-being.

Given these cultural similarities among Scotland and Arctic countries, launching a collaborative project examining the language-psychology nexus in their communities is bound to lead to mutually advantageous findings.

A new dimension to Scottish-Arctic cooperation?

The Arctic Science Summit Week, which is organised annually by the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC) and takes place in Austria this year, will be held in Edinburgh in 2024 – only a year from now. This follows increasing Scottish attendance at Arctic Circle Assemblies coupled with the country’s interest in becoming “a gateway to the Arctic”.

While the impacts of climate change are often investigated through the prism of the natural sciences, research shows it is anticipated to have negative impacts on our psychological well-being, spelling the urgency of socio-cultural and psychological research, as well as collaboration, among Scotland and Arctic nations in the years to come.