A trend to leave the Arctic

Statoil’s withdrawal from its Alaskan lease areas follows a trend among major oil companies to depart from the Arctic or postpone exploration.

Statoil’s withdrawal from its Alaskan lease areas follows a trend among major oil companies to depart from the Arctic or postpone exploration.

On Tuesday, the Norwegian oil company Statoil announced its departure from offshore oil exploration in Alaska’s Chukchi Sea, because “the leases in the Chukchi Sea are no longer considered competitive within Statoil’s global portfolio.”

In September, Royal Dutch Shell also announced its exit from the Chukchi Sea, following nine years of extensive research and exploration efforts, weathering sustained protests from environmental organizations and overcoming a series of technical and operational mishaps. Shell made its decision after investing US$7 billion without finding significant amounts of oil and gas.

Could not continue

Statoil’s holdings off the coast of Alaska include 16 lease areas acquired in February 2008 located roughly forty miles to the north of Shell’s Burger exploration area.

In addition to its own leases, Statoil will also give up stakes in fifty leases in the Chukchi Sea’s Devil’s Paw prospect area, located southwest of the Burger prospect, held in partnership with by ConocoPhillips and Chinese company OOGC America Inc.

In total Statoil spent US$23 million on acquiring the lease areas during the 2008 auction round, which were set to expire in 2020. This follows the Obama administration’s decision in October 2015 to not extend Shell’s and Statoil’s leases due to a lack of specific exploration plans.

- Since 2008 we have worked to progress our options in Alaska. Solid work has been carried out, but given the current outlook we could not support continued efforts to mature these opportunities, Tim Dodson, Statoil’s executive vice president for exploration explained.

Undermine Alaska’s economy

The Chukchi Sea holds an estimated 15 billion barrels of recoverable oil. The amount of economically viable recoverable oil, however, is almost certain to be significantly lower. The remoteness of the region and extreme climatic conditions, including seasonal ice coverage, add significant costs to the exploration and recovery of hydrocarbon resources.

Statoil’s decision to depart from the Chukchi Sea represents the second setback for Alaskan offshore developments in as many months. State and federal officials have long been at odds about which areas to open for hydrocarbon exploration and how much environmental and regulatory oversight is needed.

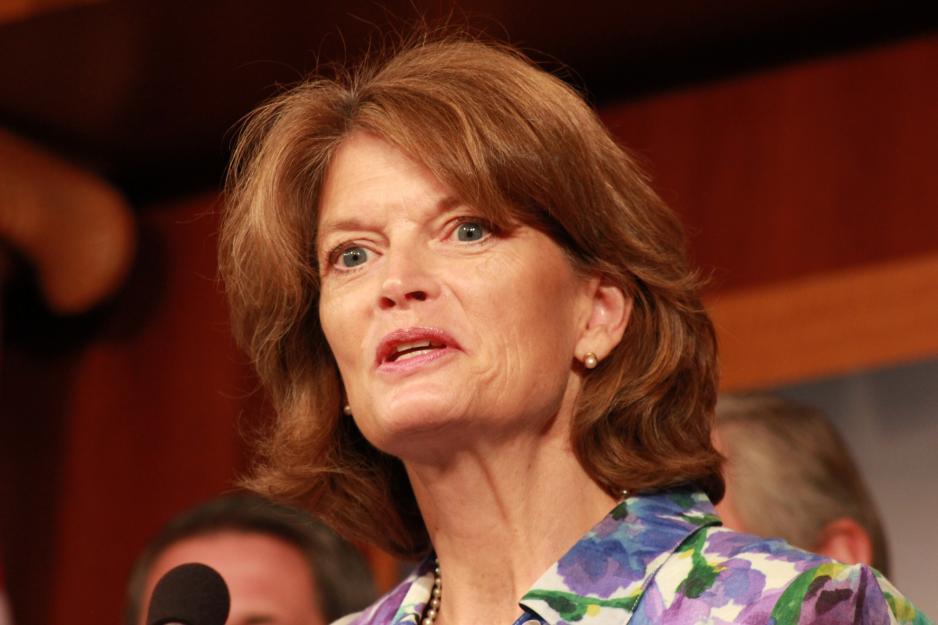

The concern that federal regulations stifle development in the state was also echoed by U.S. Senator Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, who cited the difficult-to-navigate regulatory climate and red tape as the main factor for Statoil’s decision to withdraw from its Alaskan holdings.

- Low oil prices may have contributed to Statoil’s decision, but the real project killer was this administration’s refusal to grant lease extensions; its imposition of a complicated, drawn-out, and ever-changing regulatory process; and its cancellation of future lease sales that have stifled energy production in Alaska. These actions threaten to undermine Alaska’s economy, our security, and our environment, Murkowski says.

The high costs of developing the required infrastructure is also reflected in Russia’s announcement earlier this week to welcome Chinese firms to take part in Russia’s offshore Arctic projects. (Illustration image: Wikipedia/Krichevsky)

Economics

Nonetheless, while regulatory and environmental challenges may be significant, they represent anticipated hurdles, the rapid decline of oil prices over the past 12 months on the other hand has emerged as the primary obstacle to the development of most Arctic offshore resources in economically feasible way, at least for the foreseeable future.

The Arctic’s challenging economic environment for offshore hydrocarbon exploration coupled with the recent decline in oil prices and uncertain regulatory environment have triggered a number of departures from the Arctic. In Greenland, French utility GDF Suez, Denmark’s Dong Energy, and Statoil have all recently given up oil and gas exploration licenses on the country’s west coast. In addition, Cairn Energy’s unsuccessful attempts to find commercially exploitable amounts of oil and gas on Greenland’s west side in drilling eight wells in 2010 and 2011 are well documented.

The withdrawal from the region or postponement of offshore exploration isn’t limited to the United States and Greenland; Russia’s Rosneft suspended its exploratory work in the Kara Sea until at least 2018 following the end of its partnership with Exxon in the wake of economic sanctions against Russia. France’s Total also pulled out of a natural gas project in the Russian Arctic earlier this year.

Uncertainty and high costs

Statoil’s decision to abandon its Alaskan prospects is part of the company’s efforts to increase cost savings and reduce capital expenditures. Earlier in the year it announced to delay two of its biggest offshore development projects: Johan Castberg and Snorre 2040.

The company announced to postpone the decision to continue on Johan Castberg, located in the Barents Sea and representing one of Statoil’s largest remaining oil reserves on the Norwegian Continental Shelf, until the second half of 2016. The formation’s complex structure will require significant capital expenditure to develop and investment decisions are expected for 2017. Similarly, the progress plan for Snorre 2040 - preliminary decision to implement (DG2) – is now expected by the end of 2016.

Uncertainty over the development of offshore Arctic oil and gas resources, especially in areas with seasonal ice coverage, and the high costs of developing the required infrastructure is also reflected in Russia’s announcement earlier this week to welcome Chinese firms to take part in Russia’s offshore Arctic projects.