Time to Invest in the North

Inuit hunter feeds his child with still warm meat from just hunted ring seal near Pond Inlet, Nunavut, Canada. (Photo: Peter Prokosch, GRID Arendal)

This is an editorial originally published in Toronto Star. Republished with permission

After years of scientific research at a cost of more than $100 million, no one can accuse Canada of not doing its homework on the claim it submitted to the United Nations last week asserting sovereignty over vast swaths of the Arctic seabed.

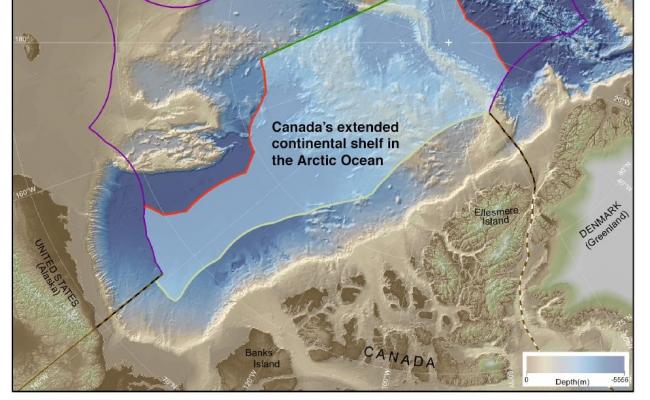

Canada is now claiming an area of the Arctic sea floor that includes a stretch from the top of Ellesmere Island along an undersea ridge to the North Pole — and more than 200 kilometres beyond.

Still, making its case to the UN won’t be a slam dunk.

Canada’s claims are contested by Denmark, the United States and — most forcefully — Russia, which has built a military base on an island in the waters of its new Arctic shipping route, complete with anti-ship missile launchers and air defence systems.

But it wasn’t Russia’s aggressive moves in the Arctic that pushed Ottawa’s hand.

The impetus seems to have come courtesy of U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo when he threw down the gauntlet and declared Canada’s claim over the Northwest Passage “illegitimate” in a speech he made to the Arctic Council in May.

No one expects sovereignty over the area — home to increasingly important shipping lanes, oil and gas and other natural resources — to be settled soon.

In the interim, there are three fronts Canada can move on to further its claim and prove its interest in the region.

To start, Canada should invest in the infrastructure needs of northern communities and Inuit, who, after all, have navigated and protected Arctic lands and waters for centuries.

Indeed, it was an effort to lay claim to land in the far north before Moscow could, that led the government to forcibly relocate Inuit to Resolute Bay in the high Arctic in 1953.

Also read

Inadequate housing and overcrowding, combined with poverty and undernourishment, led many who were relocated there to contract tuberculosis.

Tragically, too little has changed since, not just for the inhabitants of that community but for others across Nunavut.

An Inuit person, for example, is still some 300 times as likely as a non-Indigenous Canadian to contract tuberculosis.

Poverty and overcrowded housing contribute to poor school performance, the highest rate of family violence in the country, an infant mortality rate three times the national average and a tragically high incidence of suicide.

The Trudeau government has begun to take steps to improve the desperate conditions so many Inuit live in, with hundreds of millions of dollars for housing and nutrition programs in the territory.

Also read

Canada must prove, too, it is capable of managing the fragile Arctic environment.

In 2016, the Trudeau government made a fine start on that when it imposed five-year development restrictions that banned offshore drilling in our Arctic waters.

Still, much more must be done in light of a report released in April from Environment Canada that found annual temperatures in this country are increasing at twice the global average.

Finally, Canada must build a more robust coast guard to operate crucial search-and-rescue missions, respond to environmental disasters, aid navigation and manage marine traffic.

That will be a challenge. More than one-third of its 26 large vessels have exceeded their expected lifespans.

In light of that, Ottawa’s May announcement that it is buying two more Arctic patrol ships, may seem like a drop in the bucket. But, it’s a start. And it’s on top of six other vessels currently being built for the navy, all of which are ice-capable.

The fact is, if Canada is going to fight for its Arctic dreams, it must also invest in its northern lands and peoples. Otherwise its submission to the UN isn’t worth the paper its written on.