Strong Security Focus in Canada's New Arctic Foreign Policy

Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mélanie Joly, introduces a new Arctic strategy composed of four pillars: asserting sovereignty, pragmatic diplomacy, leadership on Arctic governance and more inclusive diplomacy. (Photo: Mathieu Girard/Global Affairs Canada)

"The Arctic is no longer a low-tension region," said Canada's minister of foreign affairs. Ottawa is now initiating an Arctic security dialogue, strengthening the security perspective at a regional level, and opening new consulates in Anchorage and Nuuk.

Canada recently presented its new Arctic foreign policy, also referred to as a diplomatic strategy.

The update occurs in a landscape of intensified geopolitical competition and climate change with wide-range consequences.

"The Arctic is no longer a low tension region. We live in a tough world, and we need to be tough in our response," says the Canadian MFA Mélanie Joly (Liberal).

Joly maintains that competition is increasing worldwide and that the Arctic region is not immune to this.

"Many countries, including non-Arctic states, aspire for a greater role in Arctic affairs. The evolving security and political realities in the region mean we need a new approach to advance our national interests and to ensure a stable, prosperous, and secure Arctic, especially for the Northerners and the Indigenous Peoples who call the Arctic home," she emphasizes.

Strategic challenges

• The strategy refers to Russia's warfare in Ukraine having spillover effects in the Arctic – and emphasizes Russian military buildup in the region, use of hybrid measures below the threshold of armed conflict, and increased dependence on China.

• "While the risk of military attack in the North American Arctic remains low, the region represents a geographic vector for traditional and emerging weapons systems that threaten broader North American and transatlantic security," reads the document.

• From the Canadian point of view, other possible threats are identified, such as increased Russian activity in Canadian air approaches, China's regular deployment of research vessels and surveillance platforms to collect data with dual-use potential (both civilian and military), as well as a general increase in Arctic maritime activity.

Assertion of sovereignty

"Our new Arctic foreign policy has key pillars. The first is, of course, to continue asserting Canada's sovereignty, including over the Northwest Passage. Diplomacy and defense go hand in hand," maintains Joly.

“Climate change is increasing access to Arctic resources and shipping lanes, enticing nations to the region and heightening competition. This evolving environment creates new security challenges," says Canada's Minister of National Defense, Bill Blair (Liberal), and continues:

"Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy responds to these growing challenges with a focus on asserting our sovereignty in the North, while supporting prosperity for those living there. This new policy complements our defense policy, Our North, Strong and Free, which will see us expand our presence in the North.”

The new updated Canadian defense policy was launched in April.

Central measures for assertion of sovereignty

· Bridging the intelligence gap: Federal authorities will expand information sharing with relevant territorial, provincial and Indigenous governments on emerging and developing international Arctic security trends, including foreign interference threats.

· Strengthen research security: Federal authorities will support territorial, provincial, and Indigenous authorities in taking into account a national security lens to foreign research in Canada’s Arctic. The focus is particularly on research with foreign participants that can have both civilian and military application.

· Bolster regional security architecture: Canada will also initiate an Arctic security dialogue with the ministers of foreign affairs of like-minded states in the region, which is already underway: This fall, Canada hosted a Canadian-Nordic strategic dialogue among the ministers of foreign affairs in Nunavut. In December, the MFAs in Canada, the USA, and the Nordic countries also gathered on the sidelines of the NATO Foreign Ministers' in Brussels.

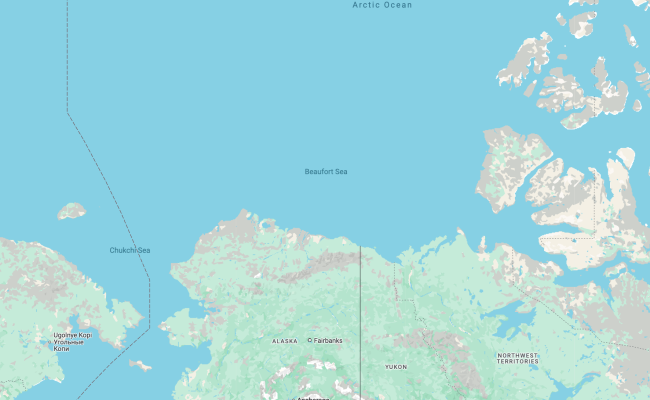

· Managing Arctic boundaries through a rules-based approach: In September, Canada launched new border negotiations with the United States over the Beaufort Sea and is also in the process of completing the implementation of the border agreement with the Kingdom of Denmark over the island of Tartupaluk (Hans Ø).

The ministers of foreign affairs and other representatives of Canada, the United States, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands discussed regional security on December 3rd on the sidelines of the NATO Foreign Ministers' meeting in Brussels. Here, Mélanie Joly emphasized the need for Arctic states to lead on Arctic security issues. (Photo: the Faroese Government)

Pragmatic diplomacy

The policy's second pillar is advancing Canada's interests through pragmatic diplomacy.

"Threats to Canada’s security are no longer bound by geography; climate change is accelerating rapidly; and non-Arctic states, including China, are also seeking greater influence in the governance of the Arctic. To respond, Canada must be strong in the North American Arctic, and it requires deeper collaboration with its greatest ally, the United States," states Joly in the foreword to the strategy.

"Canada must also maintain strong ties with its 5 Nordic allies, which are now also all NATO members," she adds.

- Canada will continue to advance bilateral cooperation with the United States in the North and explore new avenues of cooperation in critical areas of national interest, including security and safety, science and research technology, and energy security.

- Ottawa also seeks more bilateral and regional cooperation with the Nordic countries in several areas, such as Arctic science and technology, climate change, culture, defense, and security. A new position will be created in one of Canada's Nordic missions for increased coordination and information sharing, including on security issues.

Not least, the focus is directed toward close neighbors in the North American Arctic:

"With Alaska in the west and Greenland in the east, we will open new consulates in Anchorage and in Nuuk to be where it counts," says Joly.

More on the view of Russia

· Russia's warfare in Ukraine has made cooperation with Moscow on Arctic issues "exceedingly difficult for the foreseeable future," Joly underlines in the strategy's foreword.

· Under the heading of pragmatic diplomacy, it is stated that Canada will continue to hold Russia accountable in regional and multilateral forums and maintain its position of having limited engagement with Russian officials in such formats, including the Arctic Council.

· "It is for Russia to create the conditions that will enable a return to political engagement and cooperation by ending its war in Ukraine and acting in accordance with international law," reads the strategy.

Canada's pragmatic diplomacy is also directed toward non-Arctic states and actors.

Guided by several principles, such as respect for Arctic states' sovereignty, sovereign rights, and jurisdiction in the Arctic, Ottawa will place particular emphasis on collaboration with parties in two regions: the North Atlantic (primarily the EU and the UK) and the North Pacific (Japan and Korea).

Leadership in Arctic governance

The third pillar consists of Canada wanting to play a leading role within Arctic governance.

The main focus is strengthening the Arctic Council as the preeminent forum for cooperation in the region.

"Canada will not allow Russia’s actions to undermine the integrity or functionality of this important body. The people of the Arctic, who benefit so deeply from the important work of the council, should not be made to suffer because of Russia’s choices," reads the strategy.

Ottawa will increase its contributions to the Arctic Council to enable greater Canadian engagement and leadership in its projects and to provide stronger institutional support for its work. The country will also fund innovative Indigenous and youth ideas in the council.

Such support is seen as critically important as the council continues to scale up its activities. In February, all Arctic states agreed that the council’s working groups could resume official meetings in a digital format.

Canada will also increase its leadership in the Arctic Council in preparation for its third chairship of the forum in the period 2029-2031.

The chairship program is to be designed in cooperation with council partners, the permanent participants (Indigenous organizations) from Canada, as well as Canadian territorial and provincial authorities, and other Indigenous partners.

Inclusive diplomacy

Canada also aims for a more inclusive approach to Arctic diplomacy. This is the strategy's fourth pillar.

First and foremost, the diplomatic efforts in the Arctic are to be informed by and benefit Arctic and northern Indigenous peoples, as well as others who live in the North.

A significant step is to create the position of Arctic ambassador.

The Arctic ambassador's responsibilities will include linking domestic issues with those relating to foreign affairs, serving as Canada’s Senior Arctic Official in the Arctic Council, advancing Canada’s polar interests in multilateral forums, engaging with Arctic and non-Arctic counterparts, and raising awareness internationally of Indigenous rights in the Arctic context.

In carrying out these duties, the ambassador will work closely with Arctic and northern Indigenous peoples, other northerners, and relevant territorial and provincial governments.

Ottawa will also support the representation of northerners and Indigenous peoples on the world stage and increase the number of such voices at Global Affairs Canada.

In addition, promoting Indigenous and northern foreign policy priorities, such as cross-border mobility, is important within this pillar.

Natan Obed, President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, speaks at the launch of Canada’s new Arctic foreign policy. To the left: Kluane Adamek, Yukon Regional Chief in the Assembly of First Nations, Minister of Foreign Affairs Mélanie Joly, and Minister of Northern Affairs Dan Vandal. To the right: Premiers of the Northwest Territories, Yukon, and Nunavut: R. J. Simpson, Ranj Pillai, and P. J. Akeeagok, respectively. (Photo: Mathieu Girard/Global Affairs Canada)

Anchored in the North

An important dimension of the new Arctic strategy is also its anchoring in the Canadian Arctic and Northern Policy Framework from 2019. It was developed together with Indigenous peoples and authorities in northern territories and provinces.

“I am proud to support a new Arctic Foreign Policy that includes northern Indigenous knowledge, and reflects on the needs and priorities of the North," says the Minister of Northern Affairs, Dan Vandal (Liberal).

"Placing Indigenous voices, knowledge, and wisdom at the foreground of both the policy and its implementation will ensure that the future of the Canadian Arctic on the international stage is shaped by the communities who have called the Arctic home since time immemorial," he adds.

Natan Obed, President of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, an organization representing 53 Inuit communities in the Canadian Arctic, also spoke at the strategy's launch.

“Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland in Canada, makes up 40 percent of Canada’s land area and all of its Arctic coastline. Security and prosperity of Inuit Nunangat is a shared priority for Inuit and Canada, articulated through our work at the Inuit Crown Partnership Committee table," says Obed, adding:

"Building on our successful co-development of elements of the Arctic Foreign Policy through ICPC, we are committed to continue work to ensure that Inuit and Canada jointly deliver on the AFP’s strong ambitions.”

Read the entire strategy here.