Science literacy in the north: Do we forget about our youth?

The recent announcement by U.S. President Donald Trump that the United States would withdraw from the Paris climate accord has blown up dust all over the world. Although his rather bold "America first" approach did indeed meet with some approval, the broader majority, both nationally and internationally, disapproved of President Trump’s conclusion. With a touch of irony, France’s President Emmanuel Macron for instance rebuked Mr Trump and called for "Make our planet great again".

High North News talked to Ken Coates, Canada Research Chair in Regional Innovation at the University of Saskatchewan, about global phenomena that go hand in hand with President Trump’s decision and issues such as climate change, global warming and sea-level rise: the credibility of science, the problem of lacking scientific literacy among our society and how it all relates to the North.

Science – a neutral enterprise?

The past century has seen an exponential growth in science and applied scientific knowledge worldwide. Not only have been more and more PhDs granted or scientific papers published, but the growth in patents has continued to be exponential. Despite potentially justified criticism on the quality of (some) scientific achievements and findings, today’s society produces knowledge at a rapid pace.

"However, we also live in a time when decisions are reached – for instance in the political sphere – with people simply not knowing the science", says Mr Coates.

"Theoretically available to be used for good or evil, science can be considered a neutral enterprise. Yet, it comes with enormous moral questions, as we see for instance in the process of cloning or the study of genetics. It is nowadays scientifically possible to create ‘designer babies’. But does such a scientific possibility makes this opportunity morally right?"

Science and technology have drastically transformed our lives for centuries. But are we actually able to properly engage with science-related issues or with general ideas of science as such? Do we have the capacity to question a politician’s statement on climate change being a moneymaking hoax or are we simply overwhelmed by all the available information out there? And are we even properly trained and educated to tackle the vocational challenges of the 21st century?

What about scientific literacy?

The OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) defines a scientifically literate person as "willing to engage in reasoned discourse about science and technology", holding three core competences:

- Explaining scientific phenomena

- Understanding scientific questions

- Using scientific evidence

Mr Coates, who also presented at this year’s High North Dialogue in Bodø, further divides scientific literacy into three categories: "A first level concerns a high-order scientific literacy, the highly specialized knowledge of a certain field or topic that is most often honoured and achieved by those who hold advanced or graduate degrees in a field. The second level relates to so-called middle-tier literacy and relates to the ability to have a scientific discussion about an issue without having specialized, trained expertise in that matter. And thirdly, there is the practical scientific literacy and the capability to operate science-based items of daily use, but without necessarily understanding the underlying science. A microwave, for example, serves as fitting example. Hardly anyone understands how a microwave actually works but we are still able to use it."

"The problem is though that the first-level generates scientific knowledge without the two other levels being able to properly or fully interpret data and evidence", Coates continues.

"In most countries the educational system is rather backward-looking, preparing people for the past and not for the future. Yet, the problem does not only lie with a lack of education or a misguided didactic approach but essentially also in the fact of an ivory-towered language by those with specialized expertise. Moreover, a lot of research begs the key question of what a society actually wants and needs."

According to Mr Coates, scientific and technological innovation should first and foremost meet the needs of people, helping to create a society according to our wishes and specifications.

"Look at Japan and their approach to "backcasting". Based on various definitions of a desirable future, policies and programmes have been identified that connect the envisaged future with the present. Thus, societal priorities guideline the research and educational focus."

How does the Arctic fit the mould?

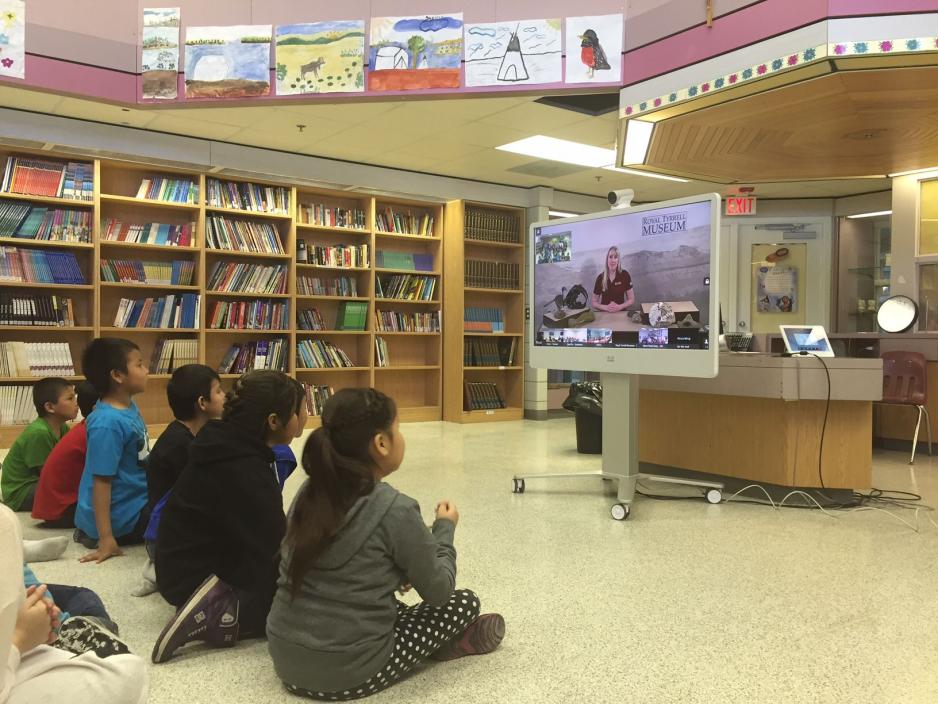

Mr Coates essentially argues that such guidelines and parameters are missing in the debate on the Arctic’s future. Moreover, scientific education for young people – especially in the northern areas of Canada and the U.S. – is rather limited, despite the fact of the youngsters being literally surrounded by scientists. He argues for an educational system that is better embedded in northern realities where both indigenous and ‘Western’ science are equally respected.

"Scientific education in the broader Arctic region should emphasize what people see and experience in their daily life. It should focus on the scientific method, demonstrating on how applied science works and how these methods can be reapplied in various settings", said Coates. In this way, an informed northern population is better able to understand their place in the world of global science and worldwide trends.

"We really have no idea how technology will develop or what kind of lasting impact technological innovation will have on regional development. What will be prospects for Arctic employment in a future where machines will outperform human beings at most tasks?" Coates asks.

"While new technologies will create some new jobs, old ones will disappear. Until now, and in general, northern economies pay relative well for workers with limited skills but a strong work ethic. But how will the North look like if everything is autonomous as, for instance, with regard to fully autonomous oil drilling rigs, with operators possibly sitting in a southern capital? The service industry may not be able to produce enough jobs and enough wealth to sufficiently absorb these changes", Coates continues.

And for the future?

With the Arctic potentially holding a $1 trillion investment base, the question remains on how the broader region and its inhabitants themselves can actually profit from such value. Are policymakers already working on strategies on how to condition the regional workforce to the challenges at hand?

"New technologies as such or related developments, such as data centres cannot be the sole foundation for the future of the region", Coates emphasises.

"It is, among others, the workforce that develops these technologies we should focus on, embedded in this particular Northern setting of indigenous knowledge meeting ‘Western’ knowledge. We need to finally and systematically build the future we want, especially in the Arctic."