Russia Launches New Nuclear Icebreaker as it Looks East for Northern Sea Route Shipping

Icebreaker Ural during sea trials in October 2022. (Source: Baltic Shipyard)

In a well-orchestrated ceremony, Russia raised the flag on the newly completed nuclear icebreaker Ural while launching the completed hull of the sister ship Yakutia into the water nearby. With oil and gas exports shifting from Europe to Asia as a result of sanctions, Russia’s icebreaker fleet will be key to the country’s Arctic hydrocarbon strategy.

The Baltic Shipyard in St. Petersburg saw the near-simultaneous presentation to the public of two new nuclear icebreakers of the LK-60 class, the most powerful icebreakers in the world.

While Ural, the third vessel in its class, after Arktika and Sibir, saw its flag raised in a ceremony attended virtually by President Putin, nearby, the next vessel of this type, Yakutia was launched into the water. The two vessels are expected to enter service by the end of 2022 and 2024 respectively.

In total Russia plans to build seven vessels of this type with five either completed or under construction.

While in the past some Arctic shipping experts suggested that a fleet of massively capable icebreakers may be overdimensioned as sea ice recedes and may no longer be needed in the future, in light of western sanctions against Russian hydrocarbon products, the renewal of Russia’s nuclear icebreaker has become of critical importance.

In order to escort oil and gas tankers on the much longer and more challenging voyage from the Yamal and Gydan peninsulas to Asia, rather than the much shorter and less ice-infested route to Europe, Russia will rely on its fleet of nuclear icebreakers.

In fact, Ural will primarily be tasked with ensuring the flow of oil from the upcoming Rosneft Vostok Oil project. Similarly, Arktika, Sibir as well as some older-generation nuclear icebreakers, escort liquefied natural gas carriers (LNG) from the Yamal LNG project on the Yamal peninsula.

President Putin during the launch of Yakutia. Source (Kremlin.ru)

How many icebreakers is enough?

Last month the Chief Directorate of the NSR warned of a lack of icebreakers to fulfill all of the escort duties in the future. Vladimir Arutyunyan, Head of Marine Operations Headquarters at Glavsevmorputv (Chief Directorate of the Northern Sea Route) explained: “We are short of icebreakers.”

He further elaborated that “the third nuclear-powered icebreaker, Ural, will start operating in 2022. It has been practically chartered for Vostok Oil. Construction of two more icebreakers is to be completed in 2024 and 2026. They will immediately go to the regions where they are highly needed.”

By 2030, Russia aims to operate at least 13 icebreakers on the route, including nine nuclear vessels. By that time the official NSR development plan foresees 150 million tons of cargo to flow along the route, a five-fold increase over the 30 million or so tons in 2022.

“There are four icebreakers under construction in the LK-60 icebreaker class. Besides, the Prime Minister has ordered to additionally build two new icebreakers of the LK-60 series, We plan to start building those icebreakers from 2023 with the financing from the federal budget,” explains Maxim Kulinko, Deputy Director of Rosatom’s Northern Sea Route Directorate.

Exporting to Asia requires more icebreakers

While some of Russia’s Arctic oil and gas ambitions may have to be curbed as a result of western sanctions, e.g. Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2, other projects are proceeding on pace, including the large-scale Vostok Oil project.

The article continues below.

Future cargo flows of oil and gas will likely be directed to the east as Europe aims to reduce to near-zero its imports of Russian hydrocarbon fuels, especially oil, lending renewed importance to a capable and reliable icebreaker fleet to ensure year-round flow of oil and gas to customers in Asia.

In fact, the first such voyage along the NSR with crude oil going to Asia arrived in the Chinese port of Rizhao last week.

The Ukraine war has also affected the composition of traffic on the route. While in previous years around one third of vessels traveling along the NSR were non-Russian, in 2022 only a handful of foreign ships ventured onto the route.

Even China’s COSCO shipping which for the past decade has sent up to 15 vessels onto the route each summer and fall did not dispatch a single ship this year.

Canada’s Northwest Passage saw high levels of activity

Canadian NWP also busy

Thus, lofty ambitions to develop the route into an international transit route with users from a host of countries in Europe and Asia aiming to connect the two continents via an Arctic shortcut, may have come to an end. The future NSR may exist solely as a hydrocarbon export highway traveled only by Russian-flagged vessels.

Meanwhile across the Arctic Canada’s Northwest Passage saw high levels of activity throughout its waters. The route saw a record-level of transits with 17 ice-strengthened commercial ships pass through the passage. This includes twelve westbound transits by eight cruise ships and four freighters and five eastbound transits by one cruise ship and four freighters.

The cargo ships all belong to Dutch firm Royal Wagenborg.

Routes open up faster than predicted

As sea ice continues to melt both routes stand to become even more navigable in the coming decades. A recent study in Global Environmental Change concludes that the navigable window along trans-Arctic shipping routes is expanding faster than models originally projected.

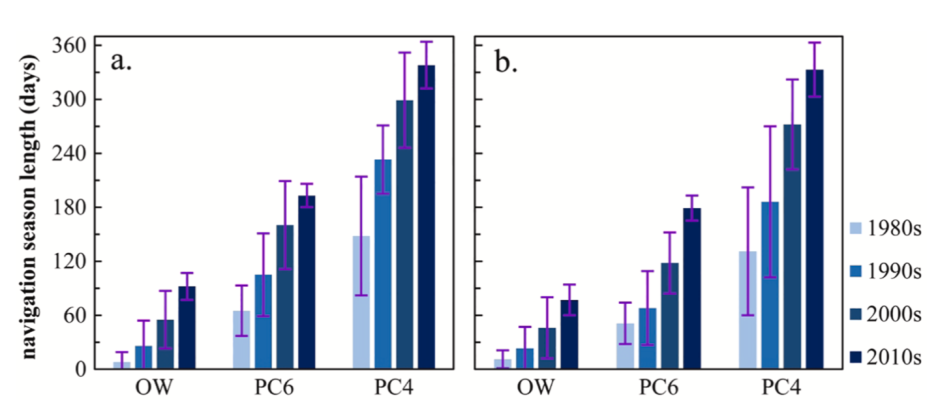

Navigational period for Open-water, Polar Class 6 and Polar Class 4 vessels on the NSR (left) and NWP (right) between 1980s and 2010s. (Source: Courtesy of Y. Cao, K. Feng, et al)

The researchers looked at how many days per year different classes of vessels, from open-water vessels with no ice protection to ice-capable ships of the Polar Class 4, could safely navigate both routes.

What the study finds is that the length of the navigation season has doubled and in some cases more than tripled between the 1980s and 2010s, to the point where the NSR is now navigable for PC4 vessels for around 330 days a year. Even open-water vessels can now travel along the route for around 150 days a year compared to just a handful in the 1980s.

This rapid opening of the region’s waterways calls for “aggressive actions to develop mandatory rules that promote navigation safety and strengthen environmental protection in the Arctic,” conclude the researchers.