New Research Identifies Arctic Communities Most at Risk from Melting Permafrost

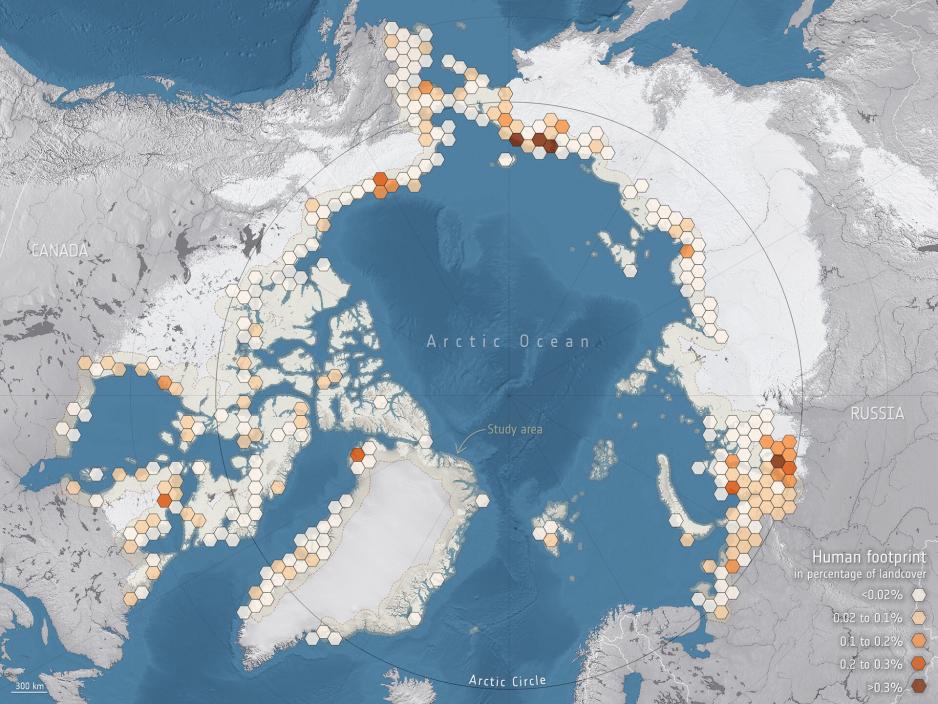

Permafrost areas (light grey) and human footprint across the Arctic coastal zone. (Source: Bartsch et al. (2021))

Rising ground temperatures and melting permafrost will adversely affect 55 percent of Arctic coastal zone infrastructure by mid-century. The impact will be largest in Russia and parts of Alaska.

A new study using data from the EU’s Copernicus satellites Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 identified communities and infrastructure across the Arctic at risk from the effects of permafrost melt over the next 30 years.

The study quantified new infrastructure constructed across the Arctic coastal zone since the year 2000 and identified what infrastructure is vulnerable to the effects of loss of permafrost by 2050.

While much research has been conducted about the release of methane from melting permafrost and its impact of climate change, this new study takes a big step in mapping the direct impact of melting soil on infrastructure and communities. It is the first circumpolar study on the state of the permafrost and recent changes using a very high resolution of one kilometer.

The researchers looked at the area within 100 kilometers of the Arctic coastline covering approximately 6.2 million km2; about 16 times the size of Norway. Using this “spatial buffer” of 100 kilometers inland from the coast allowed researchers to include communities located away from the coast, e.g. in estuaries and along rivers upstream.

Throughout the Arctic around 3.3 million people live in regions with permafrost. Increase in ground temperatures and shorter freezing seasons, as a result of climate change, has resulted in permafrost degradation across much of the Arctic.

Using latest satellite technology

The researchers relied on sensing systems aboard two satellites, the Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 earth observation satellites, launched by the European Space Administration (ESA).

"We used high-resolution data from the Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission, which carries an advanced radar instrument, and data from the Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission, which carries a camera-like instrument, along with artificial intelligence to identify communities and assets that are vulnerable to thawing permafrost," explains Dr. Annett Bartsch, lead author of the study.

The researchers concluded that 0.02% of the land area within the 100 kilometer buffer equating to around 1243km2 is impacted by human activity. These areas increased by 15 percent since the year 2000, primarily due to the expansion of the oil and gas industry.

Russia, by far, accounts for the most human-made infrastructure in the Arctic with around 700km2. Canada and the United States follow. Greenland and Norway (via Svalbard) have more limited infrastructure atop permafrost.

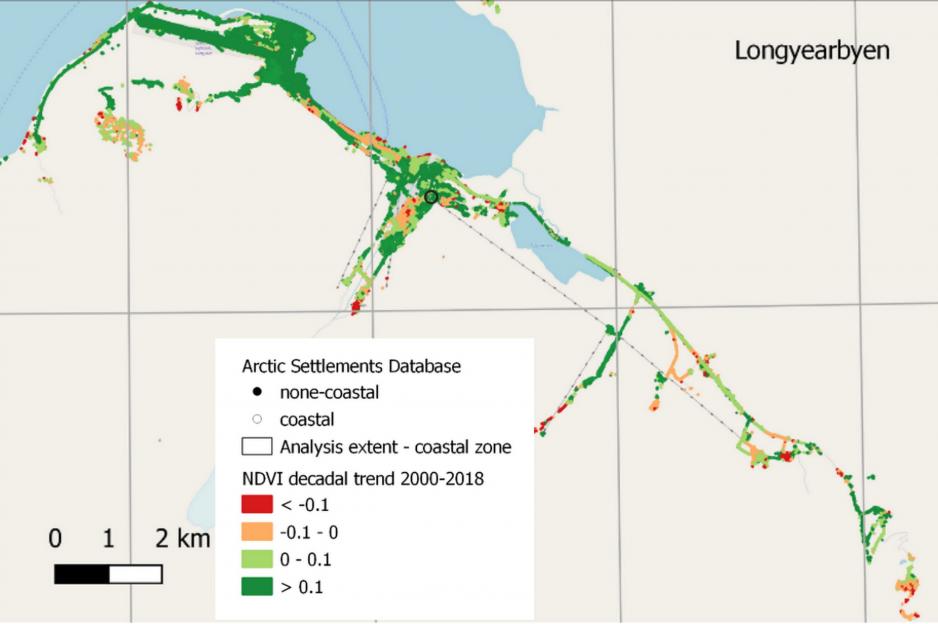

Human footprint map of Longyearbyen. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) measures change in human footprint. A value of less than −0.1 indicates new human impacts after the year 2000. (Source: Bartsch et al. (2021))

The research identified different categories of infrastructure, including fishing, agriculture, the gas and oil industry, mining, and transportation hubs. One important exclusion are winter ice roads, which serve an important function in parts of the Arctic, but can not readily be identified via satellites.

Roads and buildings represent the vast majority of human-made infrastructure in the study area, a lot of which is associated with the oil and gas as well as mining industry.

However, apart from the direct effect of permafrost melt on infrastructure, rising temperatures can also increase the risk of avalanches and landslides. A recent report about Svalbard, where temperatures have increased by four degrees Celsius since 1971, outlines how melting permafrost will alter major parts of the islands.

Projecting permafrost melt to 2050

As for the projected future ground temperature increase the study indicated that 97 percent of the mapped area shows a temperature increase of 0.8 degrees per decade. The researchers conclude that by the middle of the century 55 percent of human infrastructure will be located in zones where the ground temperature will be above zero degrees Celsius. Ten years later, in 2060, a full two-thirds will be affected.

The largest impact of melting permafrost will occur in Russia and in some regions of Alaska. In Russia melting permafrost has already resulted in the formation of hundreds of earthen “permafrost mounds”. Some of the world’s oldest permafrost is located in Russian Siberia with some soils having been frozen for 650,000 years down to a depth of 50m.

The team of researchers used permafrost ground-temperature trends going back to 1997 and extrapolated them to 2050, allowing prediction about where the temperature of the ground will be over 0°C by 2050.

This assessment, however, is just a first step, the study’s authors caution.

“The actual interpretation regarding the impacts on local communities cannot be uniformly handled for the Arctic. Country specific developments need to be considered. While we can monitor the extent of impact, the quality of local impacts can only be assessed through in-situ fieldwork”, concludes Bartch.

Such work is being conducted e.g. by the EU-funded Nunataryuk project, which began in 2017, to spend five years investigating the environmental and social impacts of thawing permafrost.