IMO Inches Forward With Ban on Heavy Fuel Oil in Arctic

MV Hanseatic in the Greenland Sea outside of Ittoqqortoormiit (Source: Jens Bludau on Wikimedia)

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) continued its efforts to adopt a ban of Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) in the Arctic by 2021 during a meeting in London. Environmental advocates laud the work, but urge Russia and Canada, the only two Arctic states yet to commit to the ban, to sign on to the initiative.

During its 6th annual meeting the Sub-Committee on Pollution Prevention and Response (PPR6) finalized the methodology for assessing the economic, social, and environmental impacts of a ban. The results of that report are expected before next year’s meeting. The committee also began to define what types of fuels will be banned and how the new rules will be implemented. The goal is to adopt a comprehensive ban in 2021 and implement it by 2023.

Due to the rising levels of shipping traffic throughout the Arctic robust measures to reduce the risks stemming from the use and carriage of HFO are becoming increasingly important. “With the countdown to a ban on HFO use and carriage as fuel by Arctic shipping now ticking away, the Clean Arctic Alliance welcomes the progress made this week at PPR 6. Today, we are one-step closer to improving the protection of the Arctic, its people and wildlife,” states Dr Sian Prior, Lead Advisor to the Clean Arctic Alliance, a group of international NGOs working towards the ban.

The use of HFO in the Arctic is growing

HFO is the most-consumed marine fuel in the region accounting for almost 60 percent of all fuels, followed by distillates, a cleaner type of marine fuel, at 38 percent and Liquefied Natural Gas at one percent. In total ships traveling throughout the Arctic carried more than 830,000 tons of HFO on board in 2015, more than twice the figure of 2012.

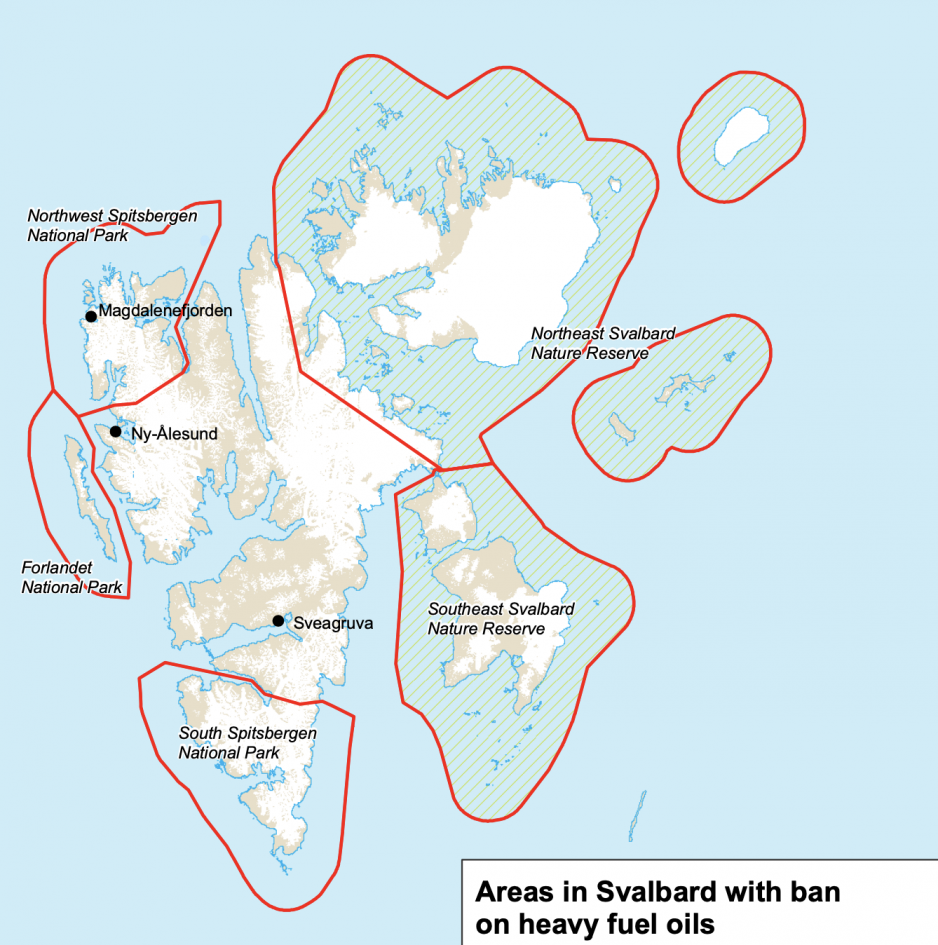

The IMO has been working towards a ban of HFO in the Arctic for nearly a decade. The debate began in earnest in 2011 when a similar ban took effect in the waters around Antarctica. So far, the use of HFO is only banned around some of the waters of the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard.

Areas around Svalbard with ban on HFO (Source: The Governor of Svalbard)

HFO, also called residual fuel oil, is a leftover product of the refining process and is an extremely viscous type of fuel. It represents a large source of harmful emissions of air pollutants, such as sulphur oxide, and particulates, including black carbon. Furthermore, in case of an accidental spill, it poses a grave risk to the region’s marine environment. In contrast to “regular” oil spills which disperse, HFO emulsifies in sea water and forms a chocolate mousse-type paste that is extremely difficult to recover.

Russia and Canada remain uncommitted

While there exists broad agreement among IMO members for banning the use of HFO in the Arctic, the region’s two largest countries, Russia and Canada, have not committed to the ban yet. Incidentally, they are also the two largest users of this type of fuel in the Arctic. In 2015 the two countries accounted for 56 percent and 6 percent of HFO use in the Arctic.

"Canada is still hemming and hawing about it, Russia is kind of negative, but they are not stamping their feet and saying 'no, no, no,'" said John Maggs, president of the Clean Shipping Coalition, who was present at the IMO meeting.

Under official Russian policy a ban on the use of HFO in the Arctic remains a “last resort.” There are however hopeful signs that it may be moving towards acceptance of a ban. In August 2018 President Putin voiced support for the ban of black carbon emissions and for the transition to LNG-powered vessels rather than the use of heavy fuel oil. In addition, Sovcomflot, the country’s largest shipping operator, including of numerous ice-capable vessels, spoke favorably about the need to transition away from HFO-operated vessels to LNG-powered ones in 2017. The company took ownership of the world’s first large-capacity LNG-powered oil carrier in late 2018 and placed orders for three additional vessels last month.

Maersk, Hurtigruten and other operators moving to cleaner fuels

Apart from regulatory efforts, a number of shipping operators, including those operating in Arctic waters, have begun to phase out HFO or even committed to transition to carbon-neutral fleets over the coming decades.

Norway’s Hurtigruten implemented a voluntary ban on HFO a decade ago and is now moving to even cleaner vessels. The company took ownership of the first hybrid-powered ice-strengthened expedition cruise ship in June 2018, with a second to follow in May 2019 and a third currently on order. The vessels are able to operate for short stints on silent, emission-free fuel cells.

Maersk, the world’s largest shipping operator, and first company to sail a container ship through the Arctic in September 2018, announced last week that it is committed to operating a carbon-neutral fleet by 2050. It has already achieved a 46 percent reduction in emissions compared to the 2007 baseline.

“The only possible way to achieve the so-much-needed decarbonisation in our industry is by fully transforming to new carbon neutral fuels and supply chains,” says Søren Toft, Chief Operating Officer at A.P. Moller - Maersk. The company says that the next 5-10 years will be crucial for developing and investing into clean fleet technology.

Ponant, a French cruise-ship operator with frequent voyages to the Arctic, also announced this week that its fleet of five cruise ships no longer use HFO since the beginning of the year.