The ICC’s 40th anniversary: International, regional and local perspectives as seen from Nuuk

President of ICC Greenland, Hjalmar Dahl (left), and External Advisor regarding the Pikialasorsuaq project, Kuupik V. Kleist (right), in front of their office in Nuuk. (Photo by Marc Jacobsen).

Since the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) was established 40 years ago, its development has been closely connected with the international strive for Indigenous peoples’ rights within the United Nations. This will continue, as Inuit across the Baffin Bay are working to establish an Inuit-led management zone between Greenland and Nunavut.

In a brand new headquarter in Nuuk, the staff of ICC Greenland are working for the transnational Inuit cause which was first articulated at a conference in 1977 and institutionalized in 1980.

High North News met President of ICC Greenland, Hjalmar Dahl, and External Advisor, Kuupik V. Kleist, in Nuuk where they shared their perspectives on the regional cooperation, local challenges and the ambitious Pikialasorsuaq project connecting Inuit across the Baffin Bay.

ICC’s main achievement

HNN: Looking back at the past 40 years, what has been the greatest achievement of ICC so far?

Hjalmar Dahl: If I am only allowed to mention one achievement, it would be the adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007. This happened after more than 20 years of hard work by ICC along with many other Indigenous organizations around the globe. This meant that we can now speak and negotiate on behalf of ourselves directly with state leaders and other powerful decision-makers on the international level.

Within the Arctic, we are also very proud of ICC’s involvement in the establishment of the Arctic Council in 1996 where we are one of the six ‘permanent participants’. Here, we especially work to draw more attention to the human dimension through our engagement in the Sustainable Development Working Group.

HNN: What are the similarities and differences in your work in comparison with ICC elsewhere in the Arctic?

Hjalmar Dahl: ICC is divided between four different countries: Russia, USA, Canada and Greenland/Denmark. Life conditions in these places are very different and it is ICC’s job to draw attention to issues that are not acceptable while working towards further unification of Inuit across national borders.

ICC is divided between four different countries: Russia, USA, Canada and Greenland/Denmark. Life conditions in these places are very different.

Elsewhere in the Arctic, people learn more about Inuit cultural background and values as part of their education than we do here in Greenland. At the same time, they are also struggling more to preserve their Inuit languages. In Greenland, we do have some negative aspects regarding the Greenlandic language in a few specific areas, but I do not believe that our language is endangered in general like it is in some Inuit communities.

Current challenges to ICC Greenland

HNN: Zooming in on your local office here in Nuuk: The Government of Greenland has announced that it will cut 2 million Danish Kroner from ICC Greenland’s annual budget the coming two years. What is the reason for this? And what does it mean to ICC Greenland?

Hjalmar Dahl: I actually did expect that we would get less because of general cut downs by the Government of Greenland, but I did not imagine that it would be so much. This year, they cut 0,5 million DKK, but the announcement that they will cut 1,5 million DKK more next year is truly scary for us! However, the fiscal year till 2022 can still be changed, and we certainly hope it will be so!

The announcement that they will cut 1,5 million DKK more next year is truly scary for us!

If the further cut downs are carried out it will mean that I will have to dismiss two out of the total four of my staff. Sometimes I am nervous about they will eliminate us, but I sincerely hope they will change their mind!

HNN: Both you and Kuupik Kleist have a background in the political party Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA), which traditionally is in opposition to Siumut that currently is in power. Do you think that has something to do with the decision to cut your budget?

Hjalmar Dahl: I am not a member of any party during my presidency of ICC Greenland, but yes, I do have a background in IA. I have been in ICC for 39 years and back when I started, those who were interested in the international aspects were mainly people from IA.

Solidarity with Inuit elsewhere in the Arctic is part of IA’s constitution. This is not written in any other party constitution within Greenland so in that way there is, indeed, a historic link between IA and ICC.

But it has changed, so today people with different party political backgrounds are members of ICC, so I do not believe that has been a concern in connection with the cut downs. I believe it has more to do with reluctance of some individuals to support Inuit cooperation in general.

Movements in ‘The Great Upwelling’

HNN: One of ICC’s most prominent projects at the moment is the one about Pikialasorsuaq – or ‘The North Water Polynya’ as it is called in English. Mr. Kuupik Kleist, you are one of three members in the Pikialasorsuaq Commission. Could you please briefly explain the importance and aim of this project?

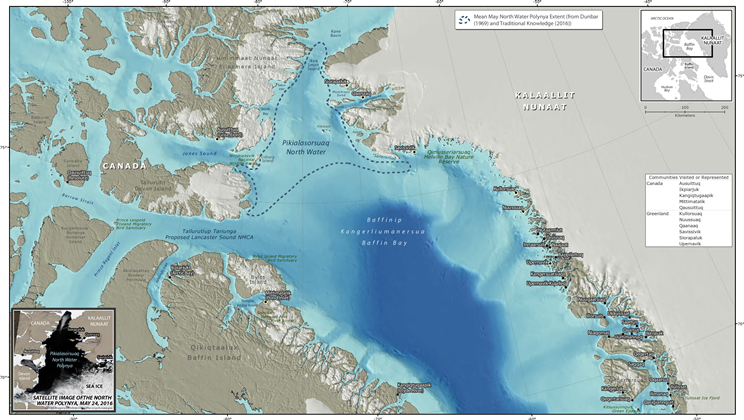

Map of Pikialasorsuaq (The North Water Polynya) and its surrounding Inuit communities on both sides of the Baffin Bay. Source: Oceans North Canada. Retrieved from: pikialasorsuaq.org/en/

Kuupik Kleist: Pikialasorsuaq – meaning ‘The Great Upwelling’ – is the largest Arctic polynya and the most biologically productive region North of the Arctic Circle. It is vital to many migratory species and – further down the food chain – also the local communities in Qikiqtani and Avanersuaq which continue to rely on its natural resources.

For generations, the Inuit have recognized it as a critical habitat, and the northern ice bridge – which helps define the polynya – was probably also the earliest human migration route between Canada and Greenland. As such it is also a symbol of the strong transnational ties between Inuit and the desire to cooperate towards a common vision for shared resources.

In 2016-2019, the Pikialasorsuaq Commission – consisting of Eva Aariak, Okalik Egeesiak and me – have led the work of forming an Inuit strategy for the safeguarding, monitoring and managing of the health of the polynya for future generations. In line with this work, we recommend that Pikialasorsuaq should be recognized as a management zone, managed by Inuit, and that a free-travel zone should be established.

HNN: Has there been any concrete progress regarding these recommendations lately?

Kuupik Kleist: Actually, there is a lot happening on the Canadian side right now where ICC Canada and the Trudeau Administration are cooperating on establishing Pikialasorsuaq as a protected area as part of the Canadian ambition of having more than 10 percent of marine conservation in 2020. However, it is a bit challenging that it is one area which is shared between Denmark and Canada and therefore it is not a unilateral decision.

ICC Canada and the Trudeau Administration are cooperating on establishing Pikialasorsuaq as a protected area.

Here in Greenland, progress has been very limited. We in ICC Greenland have made several inquiries on this matter to the Government of Greenland but have not received a single response until quite recently. We understand that there has been official contact between ICC Canada, the Canadian and Danish governments but we in ICC Greenland have not been involved nor been informed about this.

Layers of interests

HNN: Do the governments of Greenland, Nunavut, Denmark and Canada all have to agree in the end to make the Pikialasorsuaq project possible?

Kuupik Kleist: It depends on the specific dimension of the project. The question of delineating borders is of course a matter for the states, while the management of animals and regulation of shipping are primarily handled by the local governments. Additionally, there is also the international level where the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea sets the standards for shipping in icy waters. So, there are many different layers of competence that have to make crucial decisions in this case.

HNN: Is it predominantly positive that Canada now seems to have taken the first steps regarding the protection of Pikialasorsuaq, or is it worse that they continue with your agenda without informing you first?

Kuupik Kleist: It is mostly positive. It is a very complex case because the area is located where it is, and because the ecosystem is very sensible there. In Greenland, there are many conflicting interests regarding this project; for instance, there could be interest in allowing ships with cargo and tourists in the future, while interests in fisheries and perhaps oil exploitation may also emerge at some point. There has already been seismic testing in the area disturbing the animals living there.

We in the Pikialasorsuaq Commission hope that our project can be used as a model for peoples around the world who are in similar situations.

We in the Pikialasorsuaq Commission hope that our project can be used as a model for peoples around the world who are in similar situations. For example, the rain forests in South America, fishing areas in the Pacific Ocean and the Sami concerns regarding their reindeers in Scandinavia and Russia. In the big picture, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is the foundation for what we are doing.

Read more about ICC here.

Read more about the Pikialasorsuaq project here.