Heated debate about fisheries politics in Norway

To many coastal communities in Northern Norway, the fisheries are the most important industry and it contributes to jobs and to populating the entire coastline. Foto: Hilde-Gunn Bye, High North News.

There has recently been a heated debate about fisheries politics in Norway. Despite strong reactions from both coastal Norway and opposition parties, a whitepaper about the fisheries’ quota system was adopted by parliament this week. That happened one week after the Office of the Auditor General pointed out that many of the changes within the quota system in the 2004-2018 period have led to negative consequences for coastal communities.

The fish industry is one of the most important industries in Norway. To many coastal communities in Northern Norway, the fisheries are the most important industry and it contributes to jobs and to populating the entire coastline.

The regulations regarding who gets to fish, how much one may take out, and how, is all part of a complex quota system. A quota is a license to fish, and the quota system provides a foundation for regulations of how to allocate these. The system applies to various groups of vessels, from small fishing boats operating near the coastline to large ocean-going trawlers operating on the big seas.

A changing quota system

However, the quota system has been changed significantly over time. That has a.o. led to a fight over the allocation of quotas between various vessel groups as well over the consequences of this allocation for areas along the coast.

According to the Ocean Resources Act, Norwegian authorities’ management of fish resources is to secure three main goals:

- Sustainable fish stocks

- Socioeconomic profitability

- Jobs and population in coastal communities

There are, however, conflicts between these targets; in particular the latter two.

Buying and selling quotas

From the 1990s until today, the quota system has developed from vessel-regulated fisheries in which the quota would follow the vessel, into one in which the two are disconnected, and the quotas are ‘freed’. In other words, it has become easier to buy and sell quotas, and it happens more frequently.

In the 2000s, various structure regulations were introduced and it became possible to sell and transfer quotas between vessels and size-groups of vessels without selling the vessels themselves, Paul Jensen, board member of the Norwegian Fishermen’s Sales Organisation, said to High North News earlier this winter.

At the same time, quota prices have soared.

“My quota for a vessel of 11-12 meters could today be sold for some NOK 10 million (appr. € 1 million)”, Jensen said to HNN.

This, in turn, leads to the threshold being high for many young people who want to establish a career as fishermen- or women.

The quota system as well as the changes introduced have been thoroughly assessed by the Office of the Auditor General in the past 18 months. There may be decades between each time the OAG investigates fisheries policies in this way.

The OAG’s investigation showed that the changes in the quota system introduced in the 2004-2018 period have contributed to increased profitability in the fisheries fleet.

However, established fishery policy principles have been challenged, for instance, by the facts that:

- Ownership over vessels with quotas has been concentrated into fewer hands

- Fewer vessels with quotas are owned by registered fishermen

- The fisheries fleet structure is less diverse and the vessels are both fewer and larger

The OAG also found that.

- Increased quota prices has made it more difficult to recruit new fishermen

- Changes to the groups of smaller vessels has had negative consequences for coastal communities

- Several municipalities dependent on fisheries have seen reduced activity in this sector

- Several changes to the quota system have not been sufficiently assessed by the relevant ministries with regard to consequences prior to introduction

Buying and selling of quotas has a.o. led to changes in the pattern where fish is landed, according to The OAG report. Photo: Hilde-Gunn Bye, High North News.

They conclude that the sum of changes in the system has had unintended, negative consequences for the fishery activities in many coastal communities.

This applies in particular to changes introduced to the group consisting of the smallest vessels, i.e. boats smaller than 11 meters, which share a mutual dependency with land-based fish industry. The smallest vessels are less mobile and land fresh fish in their home communities more often than the larger vessels do. Access to supply of raw materials is moreover important for the land-based fish industry.

Buying and selling of quotas has a.o. led to changes in where fish is landed.

The OAG report shows that there are fewer small, local fish landing facilities than before. Fish landing is now concentrated to fewer landing facilities.

Arne Pedersen, Chairperson of the Norwegian Coastal Fishers’ Association, points out the effects of quotas being transferred upwards in the system and ending up in the ocean-going fleet.

“This development affects the land-based fish industry negatively, as many quotas have been transferred to ocean-going fishing vessels. More and more of what they catch is frozen on board the larger vessels and is sold abroad for production, via freezer terminals and centralized frozen storages. That undermines the Norwegian fish industry, which struggles to get hold of raw materials”, Pedersen argues.

“The ocean-going trawlers’ share of cod, haddock and grayfish is approaching 50 percent. Nearly 95 percent of this share goes to freezer terminals and production abroad. The Norwegian fish industry cannot compete with this at all”, he adds.

There are grave consequences for the coastal communities that lose jobs when wild fish industry and fish landing facilities are shut down in the local municipalities.

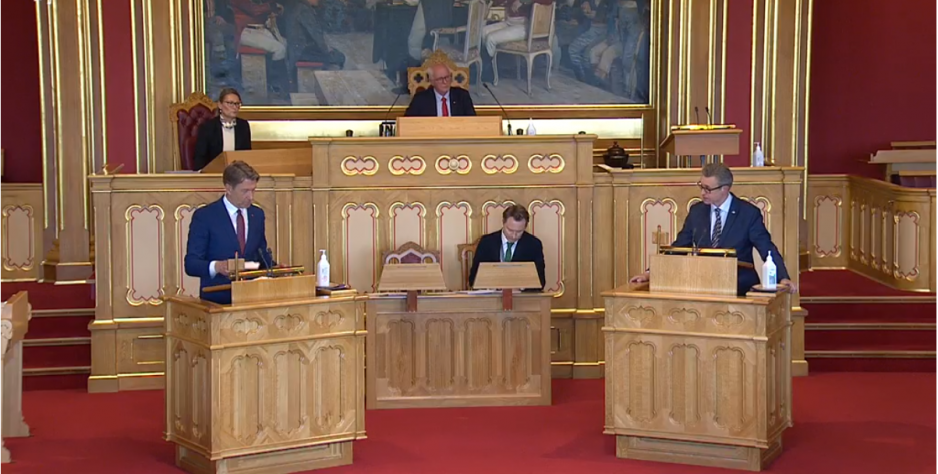

To the left, Terje Aasland (Ap), Labour Party and Minister of Fisheries and Seafood

Odd Emil Ingebrigtsen (H), Conservative Party, during the debate in Parliament, the Storting, on the new white paper. Photo: Screenshot from the Storting web-TV.

Struggle over new whitepaper

There has been a verbal rebellion along the coast for a long time. The struggle over the quotas has nevertheless intensified recently. In 2019, the government presented a new whitepaper about the quota system.

However, many have pointed out that it continues much of the fisheries policies that have been led thus far.

There are also strong reactions to the fact that the quota whitepaper was processed in Stortinget, the Norwegian parliament, just one week after the OAG presented its report.

“The consequence of the quota whitepaper is that one will eventually concentrate Norwegian fishing licenses on the hands of just a few companies who are able to pay for it”, Pedersen said to High North News. He argues that the coastal communities are the losers here.

While the government parties and the Progress Party wanted to adopt the quota whitepaper, amongst others to secure predictability for the industry, the Stortinget opposition parties argued that the whitepaper should be returned to the government and suspended until the Standing Committee on Scrutiny and Constitutional Affairs has processed the OAG’s report, which it is scheduled to do in the autumn of 2020.

Nevertheless, the whitepaper was adopted this Thursday, on the 7th of May, when the government parties and the Progress Party secured a very narrow majority of the votes.

This article has been translated by HNN's Elisabeth Bergquist.