Op-ed: Finland Retreats From the Polar Silk Road

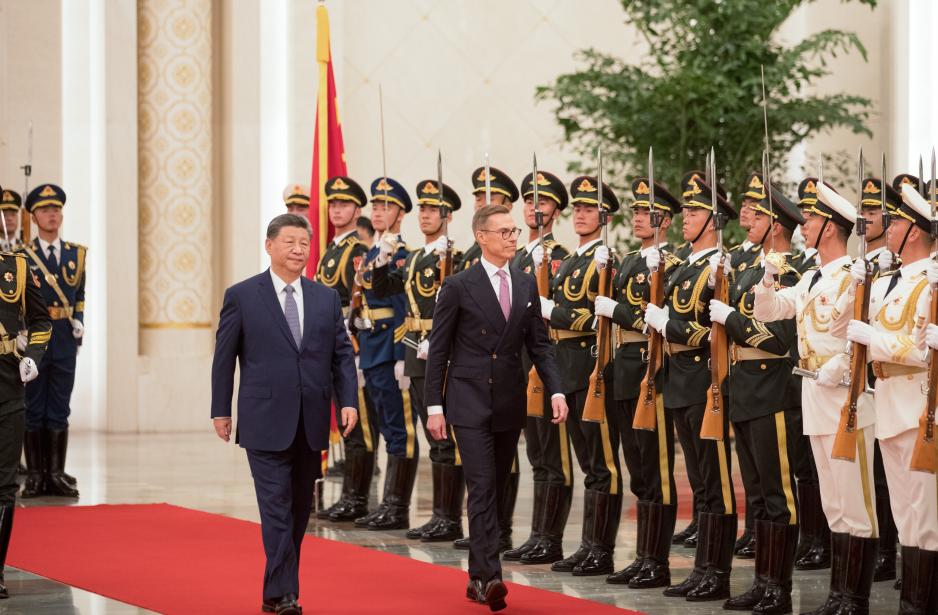

Finlands President Alexander Stubb inspecting the Guard of honour together with President of China Xi Jinping during the official welcome ceremony in Beijing on 29 October 2024. (Photo: Emmi Syrjäniemi/Office of the President of the Republic of Finland)

This is an opinion piece written by an external contributor. All views expressed are the author's own.

The President of Finland, Alexander Stubb, returned from an official state visit to China last week. The visit marked Finland’s first presidential trip to the country since 2019, and the first since Finland became a NATO member in 2023.

Sino-Finnish relations, which will celebrate their 75th anniversary next year, have evolved steadily, and the countries have managed to maintain a positive and pragmatic flow amid intensifying great power competition. China is among Finland’s most important trading partners, while China appreciates Finnish technological know-how and values the low-key approach with which Helsinki has typically dealt with China’s “internal affairs”.

Indeed, when meeting Stubb, President Xi Jinping praised the relationship as a “model of an equal relationship between two states, transcending historical, cultural and institutional differences.” Chinese state media were no less jubilant: The Communist Party mouthpiece Global Times hailed the visit as “boosting cooperation” and even mitigating “the adverse effects of geopolitical thinking within the EU”.

However, geopolitical tensions were prominently featured in the discussions between the two heads of state. In contrast to the laudatory tone of the Chinese media, the the Finnish President's official press release stated that the central topic of the talks was Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, as had been the focus of previous visits of EU leaders as well. Stubb, who earlier stated Xi could end the war in Ukraine with “just one phone call”, reportedly focused on convincing the Chinese president of the importance of the conflict for Finland and the rest of the European Union, emphasizing that Putin could not be trusted.

Yet apparently, China cannot be completely trusted either. Far from boosting cooperation, the New Joint Action Plan signed by Finland and China represents a reality different from the praises in Chinese media. Strikingly, the plan, which describes the main avenues of Sino-Finnish future cooperation, is only five pages long, compared to the 30 pages of the earlier 2019 document, which detailed various domains of increasing cooperation.

The Arctic domain is entirely absent from the new Sino-Finnish action plan

The new plan seeks to deepen “cooperation in areas of genuine interest for both sides” (emphasis added), which include low-carbon development and sustainable growth, health, food, education, sports and tourism – fields that could be described as the lowest common denominator between the two countries, and can hardly be seen as ambitious efforts to deepen the bilateral cooperation. Overall, the focal points of the plan give an impression of shrinking cooperation.

Fall of Arctic Cooperation

Noteworthy, the Arctic domain is entirely absent from the new Sino-Finnish action plan. In contrast to the 2019 plan, which envisioned deepening Arctic cooperation in the fields of law, research and marine technology, the new plan does not mention the Arctic at all.

The omission is rather unsurprising. Since the signing of the 2019 plan, the Arctic security situation has changed dramatically and Finland’s Arctic projects involving Chinese stakeholders have been quietly cancelled or put on ice. Examples include the termination of the planned Arctic railway project connecting Norway’s Kirkenes and Rovaniemi, and the Finnish security authorities’ refusal to provide satellite services to China in the Arctic Space Center in Sodankylä or to rent an airport for Arctic research flights near the Finnish Defence Forces’ firing range in Kemijärvi.

This state of affairs reflects broader suspicion towards Chinese intentions, as the Finnish media have increasingly reported on the covert activities of Chinese “united front groups” and scholars with connections to military-civilian fusion projects, for instance. Finally, in 2023, a Chinese container vessel, on its way to St. Petersburg via the Arctic Northeastern passage, destroyed a gas pipeline linking Finland and Estonia. Before its ill-fated journey, the vessel, Newnew Polar Bear, was celebrated in the Chinese media as a harbinger of increased Arctic cooperation between China and Russia. Whether the incident was intentional or not (the investigation is still ongoing), it caused a flurry of media speculation on a possible Chinese grey-zone operation in the Baltic Sea.

Since officially launching its Polar Silk Road in 2017, China has attempted to expand its presence within the Arctic countries through economic, diplomatic and scientific cooperation, but it now seems that the Arctic leg of the Belt and Road is not extending to Finland or into its neighbouring Nordic countries either. Consequently, China's Arctic expansion now increasingly relies on Russia.

Also read (the text continues)

New Cold War dynamics arising

Finland’s distancing from Arctic cooperation with China reflects deeper dynamics than mere domestic concerns. As the great power competition between “democratic” and “authoritarian” camps intensifies, Finland is increasingly “de-risking” from China, while integrating with its Western partners, especially the United States.

In addition to its NATO membership, the bilateral Defence Cooperation Agreement (DCA) with the United States, ratified last July, opens 15 Finnish military bases for the use of US forces. Within NATO’s command structure, Finland is set to be placed under Norfolk Command, whose main operational area extends from the Northern Atlantic towards the North Pole. Finnish defense responsibilities within NATO are thus in the Arctic region, highlighting the problematic nature of Arctic cooperation with China – a “systemic challenge” and a “decisive enabler” of Russia’s war as defined by the alliance.

Moreover, numerous smaller new initiatives are tying Finland into the US-led “latticework” of treaties and multilateral initiatives. These include technological cooperation agreements in sensitive areas, such as quantum computing, or in icebreaking technology, both fields in which Finland excels,

The price of propping up Russia

Officially, the new Sino-Finnish action plan does not represent a downgrade as Sino-Finnish relations are still defined as a “Future-oriented New-type Cooperative Partnership” in the Chinese typology of bilateral partnerships. Stubb’s visit to China also brought some bright spots, such as visa-free travel for Finnish citizens and new potential collaborations in trade, including the greenlighting of Finnish poultry exports.

In practice, however, the overall mood of Sino-Finnish cooperation has lowered, especially in the context of the Arctic where Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has dramatically changed the geopolitical and security environment. As long as China continues to support Russia’s war economy and share intelligence and technology with Russia, the Sino-Finnish relationship cannot be expected to improve.

Indeed, Finland’s changed approach to China provides the latest example for the Chinese leadership that there is a price to be paid for its “strategic straddle”; attempting to maintain business-as-usual relations with Europe while de facto enabling a brutal invasion in Ukraine. Naturally, this straddle is most severely felt in Russian neighbour states, including Finland, which shares the longest border with Russia in Europe.

Neither China, nor Finland, necessarily likes it, but the dynamics of the great power competition are driving them apart. Cooperation between China and the Western countries is nevertheless important, especially when it comes to climate change. While cooperation with China in the Arctic is important as well, an “ice curtain” of the new Cold War is increasingly becoming a reality in the High North.

Symbolic of the deteriorating Sino-Finnish relations, two giant pandas leased to Ähtäri zoo by China in 2017 are set to return to China eight years ahead of schedule due to financial problems. One might ask whether this reflects a broader reality for China’s Arctic cooperation in the future?