Dangerous Waters: Ukraine War Could Divert Oil Shipments from Black Sea to Arctic Ocean

The Arc5 oil tanker SCF Baltica sailing in dispersed ice in the Laptev Sea. (Source: OAO Sovcomflot)

A looming tanker war in the Black Sea as part of the larger Ukraine conflict could elevate the strategic importance of Russia’s Northern Sea Route. The country has begun sending regular oil shipments to Asia via the Arctic; and additional volume could be re-routed that way, experts say.

The Black Sea represents a key outlet for Russian oil to global markets. Every month the country exports around 60m barrels of crude oil, a third of its total, via the port of Novorossiysk.

Earlier this month, Ukraine used an unmanned sea drone to target and damage a Russian-flagged oil tanker in the Black Sea.

Ukrainian officials subsequently declared the waters surrounding Novorossiysk “a war risk area” stating “there are no more safe waters or peaceful harbors for [Russia] in the Black and Azov Seas.”

As the result of the attack on the 6,619-dwt Sig - which according to legal scholars was a legitimate target under international law – insurance rates for vessels traveling across the Black Sea have skyrocketed, impeding Russia’s ability to export oil via this route.

Many operators may simply choose to not travel into that area anymore, Byron McKinney, director with S&P Global Market Intelligence, told Politico last week.

Redirecting flow to the Baltics and Arctic

The developments in the Black Sea could accelerate Russia’s efforts to use the Northern Sea Route (NSR) to ship crude oil to international markets, especially in Asia.

In the past month alone the country has dispatched six oil tankers to China via the Arctic, a six-fold increase over the entirety of 2022.

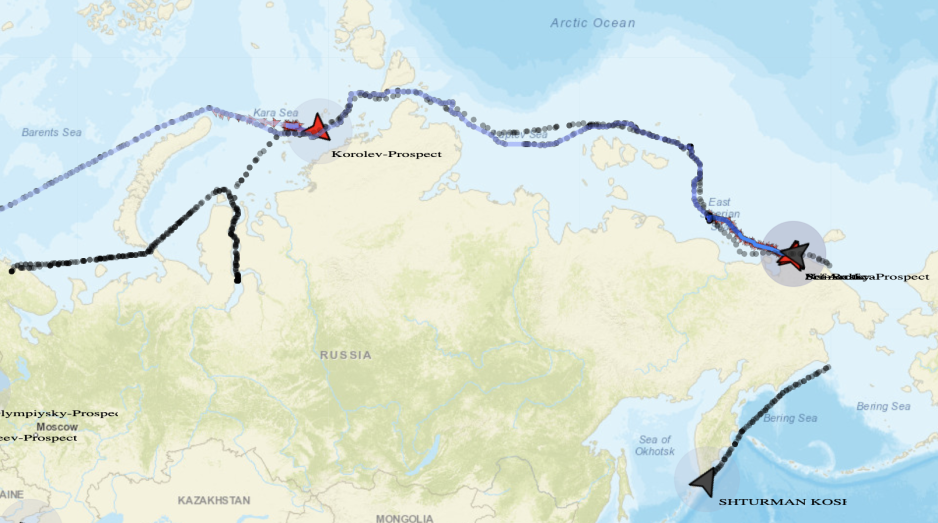

Map showing vessels tracks of current crude oil shipments to China via the Arctic. (Source: MarineTraffic)

While Russia also sends crude oil to China via pipeline, those routes are maxed out. “There is no spare pipeline capacity going eastwards - the Eastern Siberia–Pacific Ocean pipeline is utilized at a more than 100% rate,” says Viktor Katona, senior analyst at Kpler, a data and analytics firm for commodity markets.

Throughput to the Baltic Ports of Primorsk and Ust-Luga, connected via the Baltic Pipeline System, could, however, be increased, Katona explains.

“As for Primorsk and Ust-Luga, they saw exports of 1.8 Mbd as recently as May, so technically they could accommodate all the Urals flows from Novorossiysk,” confirms Katona. From those two Baltic ports oil tankers could then carry some of the oil via the Arctic to Asia during the summer and fall.

“Currently, replacement of volumes is a result of the tension on the Black Sea and Russia has already embraced possibilities by increasing the volumes via Baltic Sea ports,” explains Timur Kulakhmetov, an energy analyst with Icar Energy Services, a consultancy focusing on oil and gas.

In fact, Russia’s pipeline operator Transneft has been in the process of further expanding pipeline capacity in that region.

“At present […] Transneft is carrying out projects to expand pipeline systems to seaports, including Primorsk,” says Kulakhmetov.

Seasonal limits to Arctic route

While it would not be feasible to route all or even the majority of Russia’s Black Sea shipments via the Baltic ports and onward via the Arctic, the NSR nonetheless represents a feasible alternative for a significant volume.

“Transportation of fossil fuels through the Arctic will continue to increase to replace traffic formerly originating at ports on the […] Black Sea,” hypothesizes Kulakhmetov in a recent report published by the Energy Innovation Reform Project, a non-profit research organization.

“The Arctic's significant importance on the Russian commodity map undoubtedly remains,” he confirms to HNN.

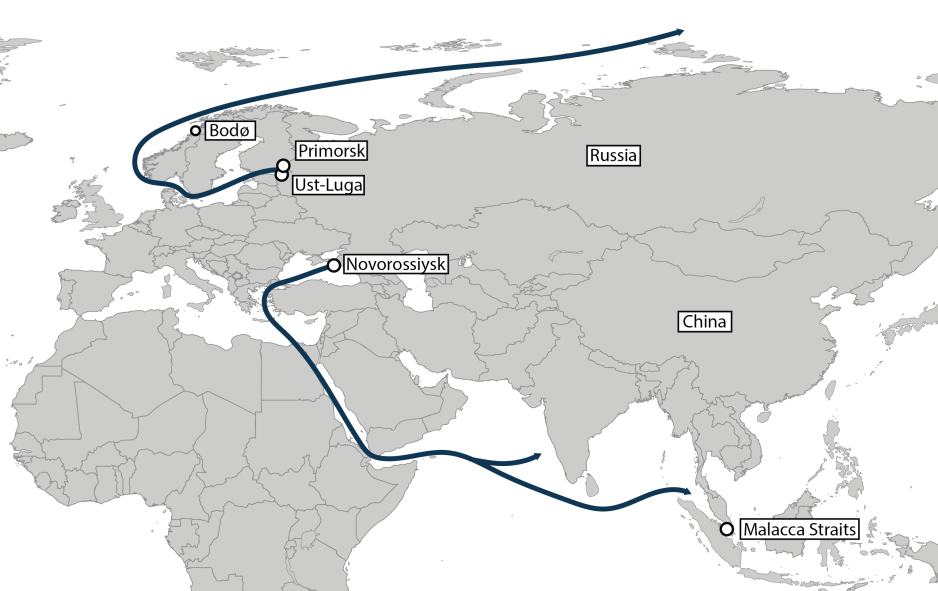

Shipping routes to Asia for oil shipments from Novorossiysk as well as Primorsk and Ust-Luga. (Source: Author’s own work)

Russia’s ice-capable fleet

Russia’s main shipping company Sovcomflot is the world’s largest operator of ice-class oil tankers, even after liquidating some of its fleet following western sanctions.

“According to our records, the Russian state-owned tanker company - Sovcomflot (SCF) alone owns over 35 ice class tankers above 70,000 dwt. There is more tonnage in operation, with varied ownership,” explains Svetlana Lobaciova, Senior Market Analyst at E.A.Gibson, a shipbroker.

Shipping traffic on the NSR traditionally peaks during September and October and experts expect to see additional oil shipments to China in the next two to three months.

Partnering with China

Russia’s efforts to develop the NSR as an alternative transport corridor are intimately connected to its growing energy relationship with China.

In June, China imported 10.5m tons of crude oil from Russia, an increase of 44 percent over last year. Every day between 1.1 and 1.3m barrels of oil flow from Russia to China.

In a sense, the Northern Sea Route provides both Russia and China with an alternative shipping corridor. While China’s primary concern sits with the Malacca Straits near Singapore – which could become a strategic choke point during future conflicts – for Russia it represents a trade route fully under its control and far removed from potentially increasingly hostile waters in the Black Sea, or elsewhere.

“Beijing sees the Arctic as a relatively politically stable alternative to traditional sea routes which use the Malacca Straits,” says Marc Lanteigne professor and researcher in politics, security and international relations at the University of Tromsø.

Purchasing oil from Russia, including from the Arctic, provides China with cheap and reliable energy, Lanteigne expands. It also helps arrest any further deterioration of Russia’s economy, which goes counter to Chinese interests.

“The Central Arctic was specifically identified as an emerging Chinese maritime transit route, so the country is getting ready for the time when such transits are more possible,” he continued.

That time may arise sooner than previously expected. While sea ice will continue to impede shipping during the winter months, Russia appears confident that it can use a four to five months window when conditions allow low ice-class tankers to traverse the Arctic.

And it may only be a matter of time until the route sees its first non-ice class oil tanker. Russian officials announced their intention to implement such shipments possibly this year – to the growing concern of environmentalists.