Arctic Shipping Requires Large-Scale Dredging with Unknown Impacts on the Environment

Summer dredging operation in the Gulf of Ob. (Source: Rosmorport)

Shipping in the Russian Arctic relies on vast dredging operations to deepen shallow coastal areas and passages along the Northern Sea Route. As a result of sanctions western dredging operators have withdrawn from Russia raising questions if shipping routes can be maintained. And the effects of large-scale dredging on the environment are largely unknown, scientists caution.

For much of the past decade a fleet of international dredging vessels has descended onto the Northern Sea Route and Russia’s Arctic river deltas each year as soon as the melting sea ice gives way to a short summer season.

Shipping along the Northern Sea Route (NSR), especially vessels transporting oil and gas resources from the projects located in the Ob river delta, relies on artificially deepened shipping lanes and port facilities.

As Russia’s hydrocarbon ambitions grow larger so does the need to expand and maintain an even greater number of shipping channels. The world’s largest dredging operators, based in the Netherlands and Belgium, have played a crucial role in deepening Russia’s Arctic waters removing more than a hundred million cubic meters of material from the ocean floor.

Following western sanctions, however, their fleets of dredging vessels will no longer return to the Arctic, forcing Russia to rely on its limited domestic fleet of aging dredging ships. A national effort to build more dredging vessels will take years and the lack of dredging capacity may hamper the country’s ability to push ahead at full speed with the expansion of oil and gas projects.

The dredging of more than a hundred square kilometers of ocean floor in the sensitive Arctic ecosystem occurs against the backdrop of limited previous research analyzing its impact. A comprehensive review of what limited research exists concluded that “concern about the impact dredging has on marine life, including marine mammals exists, but effects are largely unknown.”

Deepening of port infrastructure and shallow river deltas.

Dredging starts July 1 each year

Russia’s Hydrographic Company, a subsidiary of Rosatom, announced plans to move 13.5m cubic meters of material this summer, primarily in the Gulf of Ob. The figure represents 36 percent of all dredging planned in Russia during 2023.

A major focus of this year’s campaign will be the continuous deepening of port infrastructure and shallow river deltas.

According to Maxim Kulinko, Deputy Director of the NSR Directorate at Rosatom, the navigation channel in the Gulf of Ob of the Kara Sea will see the removal of 6.5m cubic meters of material. Other areas with dredging will be the Sever Bay seaport where Rosneft is building a massive new oil terminal for the Vostok oil project.

Additional attention will be focused on the Syradasayskoye coal terminal on the Taymyr peninsula. The two sites will see dredging in the amount of 2.7m cubic meters and 1.8m cubic meters respectively.

In addition to dredging in these new areas the Hydrographic Company will also engage in “maintenance dredging” around the seaport of Sabetta and the new Utrenny terminal serving Novatek’s upcoming Arctic LNG 2 project. These areas will see around 2.5m tons of dredging.

These efforts are part of a longer multi-year plan to create a 510 meter-wide and 5.6 km-long shipping channel to the Utrenny terminal, which involves the removal of 60m cubic meters of material by the end of 2024 at a cost of $540m USD.

Gulf of Ob Dredging area and location of Russian oil and gas projects and potential future dredging area. (Source: Author’s own work)

Dredgers left due to sanctions

As a result of Western sanctions the world’s leading operators have left Russia, affecting the country’s ability to conduct dredging operations.

Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, western companies accounted for 98 percent of dredging activity in Russia. The large-scale operations in Russia’s Arctic relied on the world’s major dredging companies to complete the work – all of them either Dutch or Belgian: Van Oord, Boskalis, Jan de Nul, and DEME.

The European companies withdrew from Russian projects in 2022 leaving only the Chinese company China Communications Construction Company (CCCC).

“Up to now, a Belgian company, DEME, the world leader in this field, has carried out some of this dredging work. With the European sanctions, Russia has announced that it wants to set up its own dredging service,” says Hervé Baudu, Chief Professor of Maritime Education at the French Maritime Academy (ENSM).

The state-owned Hydrographic Company has been tasked with creating a national dredging fleet to meet the demands of maintaining and expanding navigational areas of the NSR.

A full-fledged fleet will be necessary to conduct annual maintenance dredging, explains Alexander Bengert, the company’s General Director in a recent interview. Keeping navigational channels open will be fundamental to ensuring that NSR can reach the long-announced targets of transporting 80m tons by 2024 and 100m tons of cargo by 2030.

"The composition of the dredging fleet must cover the annual need for repair dredging work in the waters of the Northern Sea Route. The efficiency of dredging directly depends on solving the issue of proper coordination of the domestic fleet across all the projects being implemented," said Bengert.

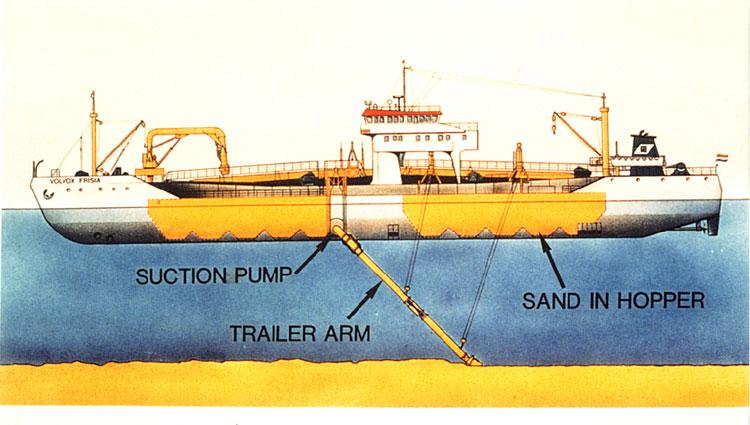

Western sanctions have led to an acute lack of adequate dredging infrastructure in Russia. The total capacity of Russia’s hopper dredgers – a kind of dredging vessel that specializes in sucking up relatively loose substances from the ocean floor – is just 39,000 cubic meters, compared to 240,000 cubic meters of Belgian company DEME, one of the world’s largest.

Schematic of a trailing suction hopper dredger. (Source: Jan de Nul)

Short dredging season

The limited seasonal navigational period requires dredging activity to occur between July 1 and November 15. Outside this period dredging vessels, which are traditionally not ice-capable or only possess light ice-classes are not allowed to operate on the route due to dangerous ice conditions.

Though Russia’s regulator has in the past ignored seasonal ice-class requirements and not enforced regulation as HNN previously reported.

Dredging eastern sections of NSR

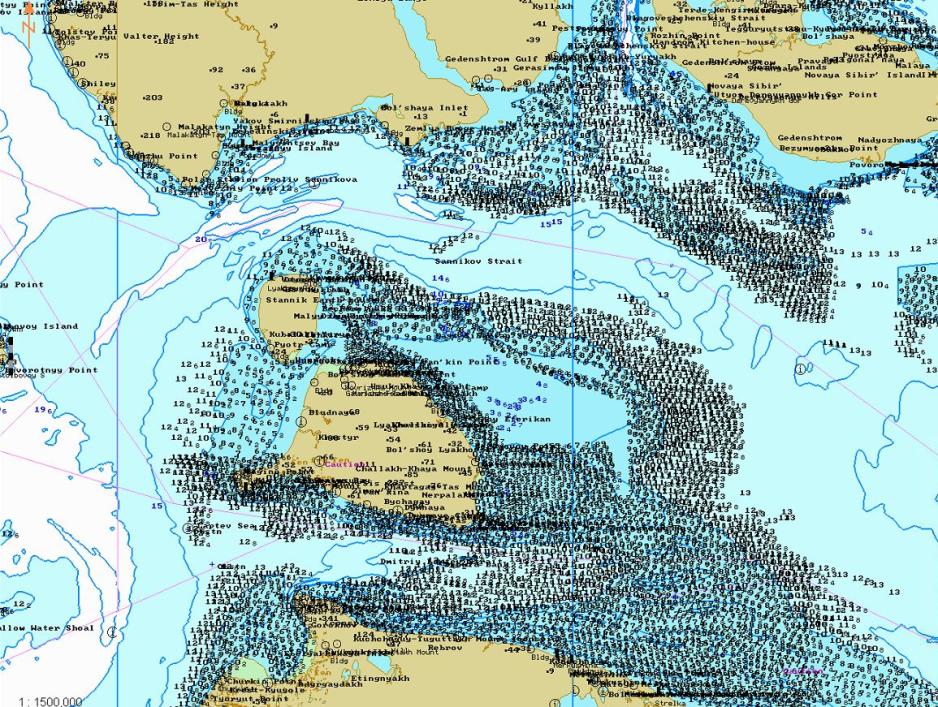

In addition to dredging in coastal areas, Russia will in the future need to deepen sections of the eastern reaches of the NSR, according to Russian hydrographers.

As vessels traveling the route become larger and have deeper drafts the water depth in parts of the Laptev and East Siberian Seas will be insufficient, explains Andrey Afonin, dean of the Arctic Faculty of the Admiral Makarov State University of the Maritime and River Fleet.

“For example, the Dmitry Laptev Strait, which connects the Laptev Sea and the East Siberian Sea. In a small area, it has a depth of less than 10 meters and it is clear that this obstacle closes the route, for example, for a vessel carrying significant quantities of liquefied gas. (... ) There, probably, it will be necessary to dig,” says Afonin.

Similarly the Sannikov Strait to the north also has a limiting depth of around 12 meters.

The shallow Sannikov and Dmitry Laptev Strait. (Source: HNN source)

Oil tankers will have deeper drafts

The issue will become even more prevalent as Arctic oil-carriers from Rosneft’s Vostok project will begin traversing the route in 2024. The project has ordered a fleet of twelve Aframax tankers with an Arc5 ice-class.

These large-size vessels will have drafts in the range of 15 meters, making them too large to pass through, among others, the Dmitry Laptev Strait. They will also have a larger draft than Novatek’s Arc7 LNG carriers.

“The Vostok oil tankers have a length of 250 meters, a width of 44 meters, a deadweight of 114,000 tons and a draft of 15 meters. The draft of an Arc7 LNG tanker is only 12 meters,” explains Baudu.

“Dredging will have to be performed in some sections,” explains Afonin.

Variable ice conditions also require vessels to deviate from routes with the most favorable bathymetric conditions, i.e. when ice conditions are more severe in the deepest parts of a shipping channel a shallower routing may have to be selected.

Also read

More shipping means more dredging

According to Rosatom, a fleet of eleven dredging vessels will be required by 2026-27 to maintain the waters of the NSR.

Russia’s fleet is simply not large enough to complete the required dredging operation on the NSR in a timely fashion, especially given the short navigation season of only 4 1/2 months.

“Russia needs a single dredging operator,” says Bengert.

“This will solve the key issue – the coordination of the resources available in the country. Amid the limited capacity of the Russian dredging fleet, the lack of coordination in dredging leads to incorrect deployment of the fleet, incorrect planning and incorrect prioritizing of projects.”

Urgently building more dredgers

It will take several years to design and construct dredging vessels to make up for the shortfall left by the departure of international companies.

We have never faced a task in this format in Russia.

“According to our calculations, we are not to see Russia’s first ship (hopper dredger) before 2027-2028. The key challenge is not the ship as it is, but the internationally-produced equipment which is beyond our capabilities so far,” Bengert concludes.

Russia’s largest shipyard, United Shipbuilding Corporation, sees similar challenges.

“While Russia has an experience in building cutter suction and multi-bucket dredgers, the situation with hopper dredgers is more complicated. We have never faced a task in this format in Russia,” added Yevgeny Leonov, Head of USC Department for Sales and Contracts.

The company is now engaged in scaling up construction of hopper dredgers and is in the process of designing vessels with 4,000-8,000 cubic meters of capacity.

According to the Hydrographic Company, during Phase 1 to start in 2023, there will be a need for one hopper dredger with a capacity of 7,000-10,000 cubic meters, one hopper dredger for 4,000-6,000 cubic meters and two additional vessels with the ability to level the sea bed.

It is a sad situation.

For the next phase, by 2026-27, the operator will additionally require another 7,000-10,000 cubic meter dredger and 4,000-6,000 cubic meter dredger and a bucket-type dredger in addition to support vessels.

In total the Hydrographic Company expects to spend in excess of EUR 200m in the next 5 years on procuring vessels for its dredging subdivision.

And dredging needs are forecasted to further increase. After 2024 an additional 5m cubic meters of material deposited in the Gulf Of Ob will have to be removed annually to ensure safe navigation in the bay.

Chinese markets offer little help

Russia’s ability to procure these vessels on the international market will be limited, explains Bengert.

“However, the global market is limited when it comes to the key types of ships required. It is a sad situation. If everybody believes that buying a good dredger in the foreign market is easy, this is not so. Only Asian countries are ready to sell, it is not so simple,” said Bengert.

And deploying Chinese vessels on a contract basis via the Suez Canal is too costly given the vast distance the dredgers would have to travel from Asia to the Arctic.

It means death for the fish stocks of the Ob.

Environmental impact of dredging

Dredging in the Arctic Ocean occurs against the backdrop of limited research on severity of its impact on its ecosystem.

A comprehensive review from 2025 concluded that “concerns about the impact dredging has on marine life, including marine mammals (cetaceans, pinnipeds, and sirenians) exists, but effects are largely unknown.

Other research suggests that digging up material from the ocean floor has a substantial effect on the ecosystem. “Removing large parts of the seabed and dumping it elsewhere can have a major impact on the ecosystem," scientists concluded as part of a larger report related to harbor dredging in Australia.

The negative impacts from drilling arise from both physical and chemical changes of the ocean floor and waters surrounding the dredge site. The removal of sediment can remove nutrients from the ecosystem and at the same time can spread toxins deposited in the ocean floor.

“It is recognised that removal of sediments may have adverse impacts on marine species and habitats. The extent of such impacts depends on the characteristics and the sensitivity of the area dredged, and of the dredging technique applied,” a report by the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (the OSPAR Convention) states.

Regional research institutes like the Ural Institute for Ecology of Flora and Fauna have long warned that dredging in the sensitive Gulf of Ob waters could cause irreversible damage to fish stocks. Sharing the Institute’s findings, the head of research, Vladimir Bogdanov, explained two years ago that the dredging is causing irreparable harm.

“When dredging work is carried out in this area, it means death for the fish stocks of the Ob. Neither sturgeon, nor whitefish, nor freshwater cod will remain. It will be a huge loss that cannot actually be restored and the ecosystem will be completely changed.”