Is the Arctic Council a Paper Polar Bear?

Reforming the Arctic Council is a monumental task. Often viewed as the poster child of regional governance and hailed as a model of cooperation across the globe, the Arctic Council will have to undergo structural changes if it wants to adapt to the new set of challenges ahead. (Photo: Arctic Council)

With more meetings and reports of meetings, is the poster child of Arctic governance overrated? Has the Arctic Council become a paper polar bear – outwardly powerful, but inwardly ineffectual?

Last week, more than 120 Arctic experts and politicians gathered in the small town of Hveragerði in Southern Iceland for the first SAO plenary meeting since the Arctic Council’s passed from Finland to Iceland earlier this year in Rovaniemi.

The Arctic Council’s journey toward a sustainable Arctic made a stop last week in Southern Iceland as temperatures slowly began to drop below 5 degree Celsius in the small town of Hveragerði. Arctic States’ representatives, Indigenous Permanent Participant organizations, Arctic Council’s Working Groups and more than thirty Observers gathered for the first Senior Arctic Officials’ (SAO) plenary meeting of the Icelandic Chairmanship.

The town of Hveragerði and surrounding geothermally active area (Photo: Richard Allaway/ CC BY 2.0)

Led by SAO chair and Iceland’s Ambassador for Arctic Affairs, Einar Gunnarsson, the plenary meeting provided an opportunity for the Working Groups to present their results of their works and highlighted the campaign against plastics in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. The participants were also updated on the progress of AMAROK, the Arctic Council tracking tool, and on the outcomes of the SDWG Plenary Thematic Discussion on Youth Engagement in the Arctic Council that took place in Reykjavik in mid-September in connection with SDWG meetings taking place in Reykjavik and Ísafjörður from 10-12 September 2019. The chair also provided a summary of the meeting of the Expert Group on Black Carbon and Methane held in Reykjavik at the beginning of October this year.

Meetings, Reports and Reports of Meeting

As this first SAO plenary meeting in Iceland came to an end, some Arctic experts started to voice their criticism about the lack of concrete outcomes from Arctic Council.

Managing Editor of the Arctic Yearbook and Arctic political scientist, Dr Heather Exner-Pirot on Twitter

Managing Editor of the Arctic Yearbook and Arctic political scientist, Dr Heather Exner-Pirot quickly took to social media to say that “with all due respect to the Arctic Council, more meetings and reports from other meetings are not impressive outcomes.” This criticism of “much work but little to show for” is not new, and the same concerns of an ineffective Arctic Council are regularly voiced after SAO and Ministerial meetings. Has the Arctic Council turned into a paper tiger – or more accurately a paper polar bear – outwardly powerful, but inwardly ineffectual? Could it be that the Arctic Council’s role in Arctic governance is slightly overrated?

As a taxpayer, I often wonder if the money spent couldn’t be put towards more productive uses.

High North News contacted Exner-Pirot to ask her to further elaborate on her statement. She explains that she has always struggled to understand the Arctic Council’s Working Groups. To her, the bi-annual SAO reports all the WGs’ activities in detail, but it mostly seems as though they have activities but no measurables outcomes. “As a political scientist, I think the AC provides great value: stability and peace for $20-30 million a year. But as a taxpayer, I often wonder if the money spent couldn’t be put towards more productive uses - ones that the average legislator or member of the public could recognize and appreciate,” she adds.

Business as Usual

Reacting to these statements, Iceland’s Ambassador for Arctic Affairs and current Chair of the Senior Arctic Officials, Einar Gunnarsson offers a more nuanced view of the purpose and outcome of the SAO meeting in Hveragerði last week. He pointed out that the meeting was the first plenary meeting during the Icelandic Chairmanship, thus the first time all state representatives, permanent participants, Working Group chairs and Observers gathered to discuss the Council’s work during the current Chairmanship and the expected outcomes at the end of the Chairmanship.

Current Chair of the Senior Arctic Officials, Einar Gunnarsson. Photo by North Norway European Office

Ambassador Gunnarsson further explains that “[These meeting] are therefore an important step in the process of implementing the Icelandic Chairmanship agenda and the Working Group 2019-2021 project work plans, towards more concrete outcomes that will be submitted to the Ministers of the Arctic States in 2021.” And, “this is usual for Chairmanships,” he adds.

This is usual for Chairmanships

The SAO Chair also pointed out this meeting “was also an opportunity for Observers to get more familiar with ongoing projects and activities of the Working Groups related to people and communities – the focus area of the meeting – and to discuss and plan with Working Groups how they can best collaborate through specific projects for the duration of the Chairmanship.” During the meeting, the Council invited the Arctic Youth Network to openly discuss how to better involve youth in the work of the Council, which resulted in some specific suggestions for action.

The Glass Half Full?

Dr Douglas Nord, one of the leading academics on Arctic governance and professor of from Umea University also prefer to see the glass half-full when it comes to the Arctic Council’s achievements. “There is always additional important work that it could be undertaking,” he says, “but if you look at what it has accomplished, especially over the last decade, its efforts are quite significant.”

The Arctic Council has indeed managed to foster collaboration across the North at a time were few thought it was even possible to create such dialogue as the region was seeing a rise of physical, economic and political changes. Nord further explains that by focusing on specific problems and issues of salience to the North the Arctic Council has encouraged the process of addressing important concerns of the region. He adds that “a major accomplishment of the Arctic Council has been to keep such disparate parties working with each other in research and policy development and making headway on real issues that affect the circumpolar community.”

Family photo at the 11th Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting in Rovaniemi. (Photo: Jouni Porsanger / Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland)

Of course, this does not mean there is no room for a healthy dose of criticism or improvement. There is still much more that could be done to broaden the work of the Arctic Council. Nord suggests there are important initiatives that should be prioritized such as developing new employment and education opportunities for the people living in the North or broadening the input of Permanent Participants.

But Nord also tries to keep things in perspective. “For an institution that is only about two decades-and-a-half old, what has been accomplished thus far is significant and compares favourably with [what] other international institutions have accomplished over similar periods of time,” he said. In terms of concrete outcomes, both Exner-Pirot and Nord agree however that the work, which is currently being done by the Council, on marine litter and plastics is quite impressive. The SAO meeting in Hveragerði served as a backdrop to discuss the next steps in the process of combating marine plastic pollution in the Arctic.

If you look at what it has accomplished, especially over the last decade, its efforts are quite significant.

The Web of Arctic Governance

The traditional understanding of Arctic politics places the Arctic Council atop of regional governance, but as Exner-Pirot points out, Arctic governance should not be viewed as a pyramid, with the Arctic Council on top but rather as a web, with the Council placed in the middle. There are other important fora relevant to the governance of the region. “Think of [International Maritime Organization (IMO), the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, the Arctic Coast Guard Forum, the University of the Arctic, the International Arctic Science Committee, the Five Plus Five Fishing Agreement, and many international environment treaties,” Exner-Pirot points out.

Managing Editor of the Arctic Yearbook and Arctic political scientist, Dr Heather Exner-Pirot, speaking at the Artctic Futures Symposium i Brussels earlier this week. Photo by North Norway European Office

Navigating in this web of Arctic governance might prove difficult and it is easy to give too much credit to the high-level political forum with lack of law-making power that is the Arctic Council. Asked if too much deference has been accorded to the Arctic Council, Nord suggests that perhaps the opposite is true. “If anything, insufficient awareness and support for its efforts have tended to me more of the case.” Nord agrees with Exner-Pirot that other fora such as the forthcoming COP 25 Conference, the IMO and the Arctic Circle Assembly can and do serve as appropriate venues for discussion of some Arctic issues and concerns. However, he adds that “the way in which the Arctic Council provides an ongoing and integrative focus to these matters is unmatched by any other body. Thus, it should remain at the centre of Arctic governance efforts.”

Not Structured to Deliver Results

For Nord, the Arctic Council’s unique ability to bring states, indigenous peoples and non-state actors together in collaborative undertakings remains relatively unseen among other bodies of the contemporary global community. And future improvements to build a stronger Arctic Council, one of the priorities of the Icelandic Chairmanship, might be to broaden its agenda to become more outcome oriented. As Exner-Pirot suggests, this might be a difficult undertaking given the current political climate and under the Council’s current structure. According to her, the Arctic Council is not structured to deliver results.

Also read

Speaking of structural changes, Nord suggests that “what is needed today is for all interested parties to give the Arctic Council more leeway to discuss matters of relevance to the circumpolar region and to direct resources to identified concerns.” According to him, “this means broadening the Arctic Council’s agenda and providing it with mandatory, on-going funding to support its mission.” The Arctic Council might need a structural makeover to secure more effectiveness in the future. Nord further elaborates, “the Arctic Council remains the right platform for effective Arctic collaboration, but it needs to be further strengthened and supported through the acquisition of additional resources and the articulation of a commonly agreed agenda for action in the coming years.”

Active Reforms, Changes and Transparency to Improve the Council

As these structural changes will have to take place for the Arctic Council to remain at the centre of the region’s governance, Arctic affairs are still at the periphery of global affairs. Voices, especially those of non-Arctic States, whose voices are much stronger in other fora, have also called for the Arctic Council to strengthen the role and the capacity of Observers. Expanding the role of Arctic Observer States and non-States actors might also be a step toward a more adaptive governance model. As Nord points out “as the organization has matured it has endeavoured to find new ways of encouraging the active involvement of the Permanent Participants, and the Observers in its affairs.”

During its Chairmanship (2019-2021), Iceland has been also trying to highlight the strengths and potential future use of Observers in an effort to show how they could be more involved and how more Observer engagement will benefit both Arctic and non-Arctic States under the present structure.

The Council needs to engage in additional internal reforms that can make its activities more transparent, understandable and consequential.

Changes in the way the Council works could also take other forms. For example, Nord suggests that efforts should be made to ensure that the Permanent Participants are actively engaged and that non-state actors can involve themselves in both the Council’s discussions and research. “However, like most international organizations, the governments of states are likely to play leading roles within the Arctic Council for the foreseeable future,” he nuances, and “the challenge is to have these states play involved, constructive and creative roles—especially when they come to occupy the chair of the body.”

These calls for restructuring the Council are not new. Earlier this year, a group of Arctic experts and researchers got together and published an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the Arctic Council to rethink both its form and function for 2019 and beyond. This article prompted some reactions and led to other researchers questioning the costs and reality of reforming the Arctic Council altogether. But the word was out, to adapt to future realities, active reforms are needed. As Nord summarizes, “the Council also needs to engage in additional internal reforms that can make its activities more transparent, understandable and consequential.”

Also read

The Arctic Council is the main element of Arctic governance. But to remain at the centre of this governance web, it will have to adapt. And fast. How it adapts will be up to the political climate of the day and those changes can take many forms. But according to Nord “securing mandatory on-going funding has to be a top priority; and these resources need to be utilized, in part, to facilitate the enhanced involvement of non-state actors in Arctic affairs. Equally important is the urgent need to restructure the working groups of the Council in order to both expand the focus of their efforts and to broaden the participation of researchers from indigenous communities and NGOs. Many of the existing working groups have become too focused on tilling well-established fields of inquiry instead of considering new challenges faced by Arctic and incorporating new researchers. By pursuing both efforts, it is my feeling that the limits of what the Arctic is and what the Arctic Council can be will be enhanced.”

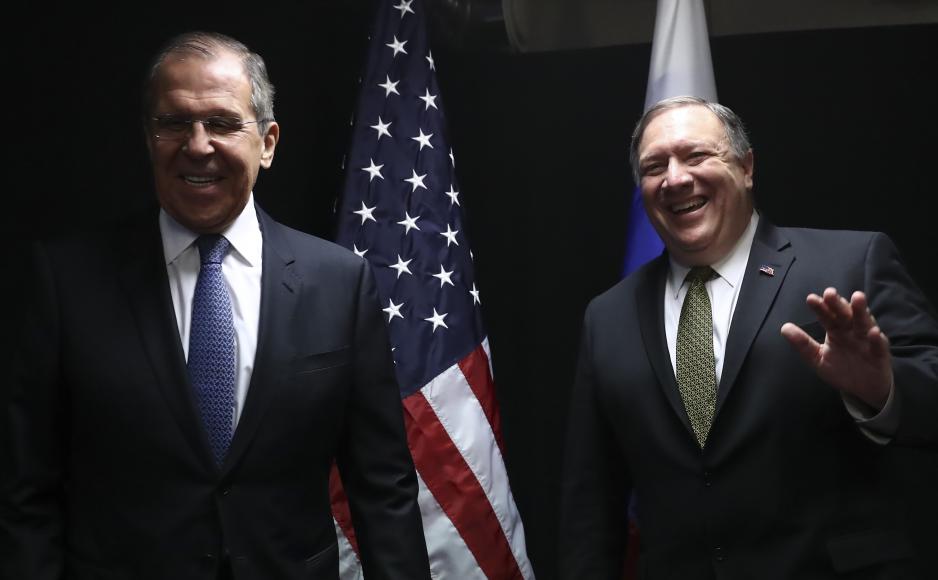

Sergej Lavrov with Mike Pompeo in Rovaniemi in May. Photo by Russias MFA

Reforming the Arctic Council is a monumental task. Often viewed as the poster child of regional governance and hailed as a model of cooperation across the globe, the Arctic Council will have to undergo structural changes if it wants to adapt to the new set of challenges ahead. Whether there is enough political willingness to do so remains to be seen.