Arne O. Holm says In an Abundance of Asian Tourists by the Border With Russia, PM Jonas Gahr Støre Appears

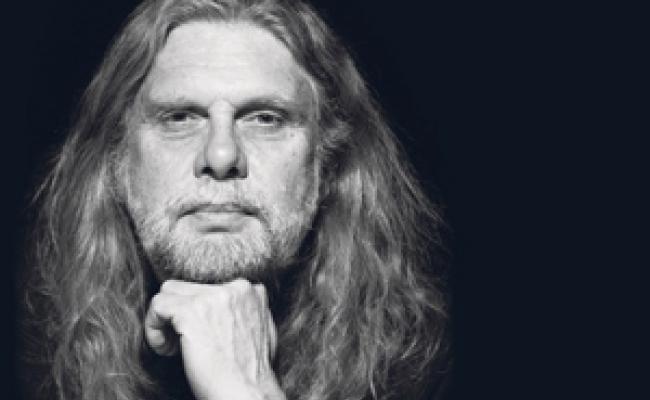

PM Jonas Gahr Støre at the Jarfjord Border Station. (Photo: Arne O. Holm)

Commentary: A nearly unpenetrable wall of Asian tourists meets me on my way into the reception at one of the overcrowded hotels in Kirkenes, Northern Norway. In a balancing act between rolling luggage as tall as their owners, I find the staircase leading to the second floor, where I meet Norwegian Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre.

He arrives straight from the airport to give the first speech of the day. Looking back at him from the audience are mayors and politicians from the nine municipalities constituting Eastern Finnmark in Northern Norway. A predominantly male assembly, which, for the next hour, will inform the prime minister about life and policy on the border with a country continuously dropping bombs over another neighboring country.

Soft shields

A few days earlier, Barents Spektake, a festival by Pikene på broen, concluded its annual cultural event in the city, now visited by the Norwegian prime minister. This year's festival was organized under the title "Soft Shields." A suitable title for a local community awarded the front-line role in a military conflict.

I have decided to follow the prime minister through his fifth Northern Norway visit since New Year's because it is no coincidence that he keeps returning to the North.

"This," he says later in the day during a break at the Jarfjord Border Station, part of the Sør-Varanger Garrison;

"... is one of the most important areas in Norway that requires development. It is not just important to the High North; it is a Norwegian matter. That is why it is important to be here."

They have done their part for the population figures.

In addition to the East Finnmark Council (Øst-Finnmarkrådet) and Jarfjord Border Station, the prime minister is opening the annual Kirkenes Conference, riding a snowmobile to a border post, holding a press conference, participating in a meeting of the local Labor Party, and finally giving a speech during a formal dinner.

All the while without a manuscript but with three main messages. It is about settlement, energy needs, and the security policy situation.

Asian tourists

While Finnmark, particularly Eastern Finnmark, is like a magnet to Asian tourists looking for darkness, cold, and Northern Lights, the Finnmark residents are moving southward, leaving behind an increasingly older and less robust population.

On the same day that Jonas Gahr Støre speaks high and low about how important it is that people live in Finnmark, Northern Norwegian mayors took a break from the nearly ritual complaints about a depopulated and aging region. On this day, Statistics Norway could reveal that the population numbers were growing in Northern Norway. Such scenes of jubilation among elected officials can only be found decades back.

It is a jubilation with a bitter aftertaste. The population growth is almost entirely due to Ukrainians fleeing the war Russia has forced them into. Today, there are equally many Ukrainians in Norway as there are people in Finnmark.

The banners from the trade union Nordens klippe add historical dimensions to Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre's speech to the members of the Sør-Varanger Labor Party. (Photo: Arne O. Holm)

While mayors are dreaming about increased tax revenues, new schools and kindergartens, the Ukrainians dream about inflicting Russia with such a crushing defeat that they can return home again.

From the lectern at the Kirkenes Conference, County Mayor Hans-Jacob Bønå (Conservative) told Jonas Gahr Støre that the county council has virtually decided that the population in Finnmark shall increase from today's 75,000 to 100,000 by 2050. That is a lofty goal. Statistics point in another direction. There is a greater chance that the population will near 50,000 than 100,000 the next 27 years.

Dreaming is allowed

But county politicians are allowed to dream and they are allowed to demand. Bønå himself is an illustration on how the Labor Party has lost its grip on Finnmark. He is not the only Conservative politician who has tipped the Labor Party out of county and municipal councils.

Of course, Støre is aware of this as he participated in a member's meeting in Sør-Varanger Labor Party late in the afternoon. Surrounded by banners from the trade union Nordens klippe, memorabilia from social democracy's heyday in the north, gravity lies heavy on both the prime minister and the assembly.

"There have been 14 interest rate increases since we came into government," explains Støre.

Aircraft filled with commuting officers.

"And energy prices have continued to increase at the same time," he says.

"So I believe that the other things we have achieved in office will remain in the background," he adds.

Guro Brandshaug, leader of the opposition in the now Conservative-run municipality, is just one of many emphasizing the gravity the population is feeling.

"A week ago at the laters, you conveyed a historical rearmament of the defense since the Second World War. We now hope you will also follow up with a historical rearmament of the civil society," she asks Støre.

The audience that applauds her has long since done its part for the population figures in the municipality.

Photo session. Jonas Gahr Støre meeting the East Finnmark Council in Kirkenes. (Photo: Arne O. Holm)

The Labor Party has a proud tradition of building industries but far less experience getting people to fill vacant jobs. And those are multiplying in Finnmark.

Earlier this week, I met the Finnmark Chief of Police, Ellen Kathrine Hætta. There are currently ten vacancies in her staff.

Commuting officers

The Armed Forces are also struggling to recruit. Many conscripts certainly want to go northward, even extending their services if possible, before turning southward again. The flights from Kirkenes on Thursday afternoons are usually filled with commuting officers.

On behalf of the municipal council, the recently elected Magnus Mæland from the Conservative Party wants to replace the word 'action zone,' which is the name for Finnmark, and parts of Troms that benefit significantly from special economic measures, with 'initiative zone.'

PM Jonas Gahr Støre has an eye for the proposal. It is even free.

However, Støre does not comment on County Mayor Bønås wish to introduce a variant of the tax regime in Svalbard in Finnmark as well.

"In the North, there are quite clear requirements and expectations. They speak in capital letters. I like it. I like clear speech," Støre says to me in a break between all the meetings and visits.

"I notice in today's situation that this part of Norway has felt the consequences of the sanctions against Russia the most."

I myself experience the politicians and Sør-Varanger residents as quiet but serious in their meeting with the prime minister. He is praised for parts of the quota white paper, the energy package, and his analyses' of Norway's relation to Russia.

I found it quite uncomfortable.

In his speech during the Kirkenes Conference dinner, the prime minister speaks English, still without a manuscript.

"Norway is a small country. We don't make the moments. We have to see the moments."

The US Ambassador nods approvingly. More than ever, the US foreign and security policy governs the development of the North.

"I have never felt fear," says an elderly woman born and raised in Pasvik on the border with Russia.

"But I found it quite uncomfortable when Chief of Police Hætta asked us to report if we saw anything abnormal."

The abnormal is normal

In Finnmark, the abnormal is normal. Now, brochures from the police encourage the local population to get in touch if they see anything "abnormal." Like mysterious people.

"It is the link between settlement and the security policy presence that perhaps makes Finnmark more special than any other place in our country," says Jonas Gahr Støre.

It is, if possible, even more cramped in the reception as I check out of the hotel. The participants at the Kirkenes Conference are replaced by Asian tourists searching for the exotic Arctic.

PM Jonas Gahr Støre is also heading home. Home to news about a stock market reaching an "all-time high" and Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise directors with seaplanes and hunting grounds on their expense accounts.

And who takes it for granted that the "soft shields" in the North will endure.