Life on the Arctic Coast: Coxswain Kim Roger Stays Calm When Put to the Test

Sørvågen, Lofoten (High North News): Coxswain Kim Roger Benonisen (38) from Sørvågen started his fishing career 20 years ago. In 2016, he and his crew shipwrecked outside the Lofoten town. During a gale, the seine got caught in the propeller, and the boat lost engine power. "We kept calm and worked systematically," he says.

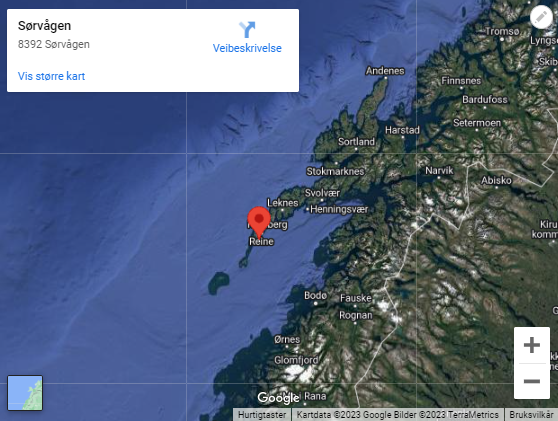

It is afternoon in the idyllic fishing village Sørvågen in the Lofoten Islands. The little town in Moskenes municipality is located at the end of the archipelago and suddenly appears in the middle of steep Lofoten mountains if one arrives by ferry across the Vestfjord.

Below the houses, in the bay, several small fishing vessels and a fish processing plant can be found. It is quiet outside, with the exception of a few seagulls crying.

A larger fishing vessel also lies along the quay, the purse seine boat Kim Roger. High North News is allowed onboard and greet the coxswain and fisherman Kim Roger Benonisen (38).

The eye is drawn to the amount of equipment located on the stern and the bow of the 50-foot-long boat; various types of ropes, winches, hydraulic hoses, a crane, and a net hauler.

The vessel is currently docked for maintenance. We enter the wheelhouse and sit down on a dark blue sofa.

20 years at sea

Kim Roger says he has been fishing his entire life. His first winter season was in 2003 – exactly 20 years ago.

"When I started fishing, I fished with line," the coxswain says.

Eventually, he got his coastal skipper certificate in order to operate a larger boat, and the first purse seine boat was purchased in 2005.

The current vessel was bought two years ago. There are four members of the crew.

What is it like to be a purse seine fisher?

"There can be some long days aboard."

"With a purse seine, we can spend longer time at sea and try several shots. If one haul is bad, we often want to try more shots – which means that we will be out for longer. With line and nets, one must leave it and go back."

The purse seine is similar to a trawl, but not quite. When the tool is put underwater, a rope is run out from a buoy and then connected with a new rope from another buoy. When the ropes are pulled together underwater, the fish is caught in the seine, which is then hauled up on the side of the boat.

"A typical catch can be around two tonnes on one shot. But we have also experienced much greater catches – and nearly empty seines," says Kim Roger.

"It is better to have smaller amounts and be more in control. We want quality in what we catch and land," he emphasizes.

The seine is hauled up on the side of the fishing vessel Kim Roger, and the fish is pumped into a chamber below deck where it lies in bulk. The fish is also pumped out to the fish landing station when delivered.

When the skrei season begins, the crew of Kim Roger often starts the fishery in Lofoten.

"But there is little skrei here at times, especially compared to 2012. There is mostly haddock here now. In the winter season, we usually go up to the sea areas off Andøya. We deliver to Andenes Fishing Reception and land our catch every day during the winter.

"We leave early in the morning and come back at night. We like it up there. It is a short way out to the fishing grounds, which means effective fishing time."

Kim Roger says that they also deliver some fish in his hometown.

He has grown up in the Lofoten town and knows most of those who live there.

What was it like to grow up in Sørvågen?

"It is a small town, but it was nice to grow up here! The activities here fit me very well. I enjoy sports and played a lot of football. But, of course, there aren't activities for everyone here."

Waiting for the quota whitepaper

When High North News asks Kim Roger what challenges he sees in the fishery industry, he points out unpredictability in the fishery policy.

"We are waiting for the quota whitepaper, which has taken a long time," he says.

"There is a lot of unpredictability regarding what it will say. The whitepaper has a lot to say for us fishers."

The quota whitepaper provides an important framework for the fishery industry. For example, it outlines how much fish can be caught, the length of the vessels, and how close to shore they are allowed to fish. The last whitepaper was presented by the Solberg government in 2020. It was highly criticized by the opposing parties and several actors in the industry.

When the Støre government took over, the Minister of Fisheries and Ocean Policy Bjørnar Skjæran (Labor) announced that there would be a quota whitepaper 2.0. It is expected that this will be finished this fall. One of the most critical issues that will likely be addressed is how structural quotas for several billion will be distributed within the fishing fleet.

In the 2000s, moving fishing quotas between vessels was possible. From the government's side, the aim was to increase profitability in the fishery industry. Structural quotas, as these are called, were to be allocated for a certain number of years. They will reach their 20 and 25-year term limits in the coming years.

What the allocation will look like has caused great debate in the industry.

"On the question of structural quotas, many in the industry have likely positioned themselves based on how things have been in the past – and invested a lot in their vessels."

"From day one, however, there was a contractual agreement on what would happen when the term limit was up. One did not have the structural quotas indefinitely – they were supposed to go back to the fleet groups they were taken from," says Kim Roger.

He also points out that the fleet group between 15-21 meters will particularly suffer if the original agreement on repatriation of structure quotas is deviated from.

The vessel lost engine power and propulsion. At the same time, the wind was getting stronger.

The coxswain also points out things that are going well in the industry.

"The past decade, there have been lots of fish, high prices, and availability. When my father started fishing, there were less fish and lower prices. The economy of the Norwegian fishery industry is better. We only have to go back to 2012 to see that we only got NOK 12 for the cod. Many likely left the fishing industry then," he says.

And what were the prices for cod this winter season?

Kim Roger retrieves the log book from the wheelhouse, looks through the numbers, and lists prices as high as NOK 46 and 50 for the kilo.

"We expect a possible decrease in the cod quota for next year by 20 percent. We will see how that turns out," he adds.

The shipwreck

While we are talking, it is almost dead calm outside. The contrast is high to the January day in 2016 when the crew of Kim Roger shipwrecked just outside Sørvågen.

"We were only 30-40 minutes outside here. The boat got the seine in the propellor, and we lost engine power and propulsion," says Kim Roger.

"This is something that can happen. At the same time, the wind and the current were getting stronger," he continues.

There is a significant risk of the boat drifting toward the shore. Things happen quickly from then on?

"Yes, but we kept calm and worked systematically."

The journalist has heard the recording of the emergency calls. One can hear a composed skipper, Kim Roger's father, and an emergency dispatcher who quickly understands the severe situation the crew finds itself in.

"We put out two anchors, but they did not take hold and just drifted over the sandy seabed," Kim Roger continues.

They also try to use the side propellers on the boat to maneuver. It helps a little.

"The side propellers may have contributed to the ship not approaching land too quickly."

Praises the rescue personnel

The strong wind has concurrently contributed to the rescue helicopters from the 330 squadron in Bodø arriving faster than usual. The flight, which usually takes around 30 minutes, now took about 20 minutes.

When the Sea King helicopter arrives, Kim Roger and his father have ended up in the sea. The two are rescued from the ice-cold ocean.

The ship capsizes with a list of 90 degrees. The rest of the crew, who are clinging to the foredeck, must eventually jump overboard to be rescued.

The boat eventually sinks, and the crew of five are taken to the hospital in Bodø.

"It was quite an experience," says Kim Roger while praising the rescue personnel.

"They are admirable and highly trained in what they do. They visited us in the hospital the same night, chatted, checked on how we were, and had coffee with us. That was great," he concludes with a smile.

This article is part of High North News' series of reports about life on the Arctic Coast. Here, you can read the previous story of 23-year-old Johan, who manages a fish factory in Lofoten.

Feel free to share tips with our journalist, Hilde Bye.

This article was originally published in Norwegian and has been translated by Birgitte Annie Molid Martinussen.